Higher Homotopy Groups

$\pi_ {k}(M)$

All maps considered in this chapter are supposed to be continuous.

Consider a map $f$ from $k$-sphere to $n$-dimensional manifold $M$. We shall always ask that some distinguished point on the sphere , the “north pole”, be sent into a distinguished base point, written $\ast$ in $M^{n}$.

For technical reasons we consider the $k$-sphere to be the $k$-cube, denoted $\mathbb{I}^{k}$. In other words

\[\mathbb{I}^{k} := [0,1] \times \dots \times [0,1],\quad k\text{ of them}.\]The entire boundary $\partial \mathbb{I}^{k}$ identified with a single point, the north pole. This choice of cubic make it much easier to talk about, for example, the composition of two maps.

We assume the reader is already familiar with the basic concepts of homotopy group, such as how we compose two elements of a homotopy group, etc.

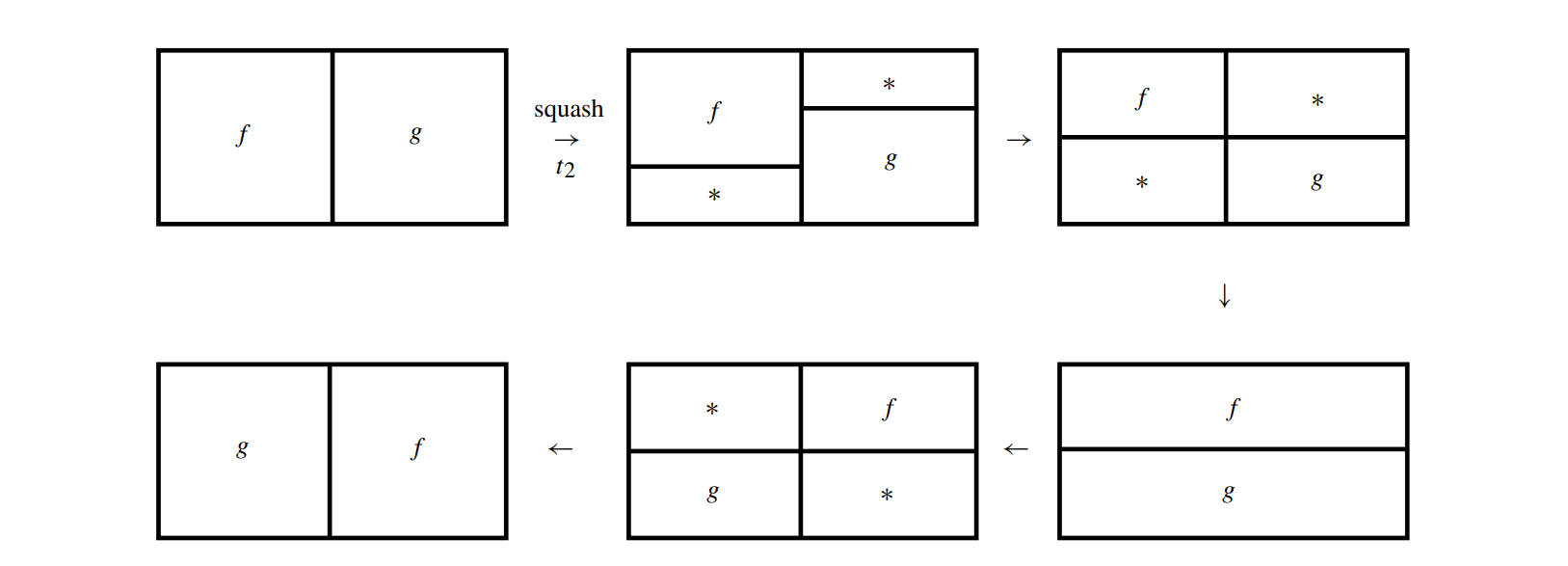

The commutivity that two elements of homotopy group is shown in the figure below.

Note that this procedure will not work in the case $n = 1$; there is no room to maneuver. This is why the fundamental group $\pi_ {i}$ can be nonabelian.

Homotopy Groups of Spheres

Now let’s talk about $\pi_ {k}(\mathbb{S}^{n})$. First consider the case $k<N$.

It seems evident that $f(\mathbb{S}^{k})$ cannot cover all of $\mathbb{S}^{n}$ if $k < n$ but this is actually false since we do not require our maps to be smooth! Peano constructed a curve, a continuous map of the interval $[0, 1]$, whose image filled up an entire square $[0, 1] \times [0, 1]$!

It is a fact that a continuous map of a sphere into an $M^{n}$ is homotopic (via approximation) to a smooth one. To be specific, the approximation Theorem states that any continuous map between smooth manifolds can be approximated arbitrarily closely by a smooth map. In more technical terms, for any continuous map $f$ and any $\epsilon>0$, there exists a smooth map $g$ such that the distance between $f(x)$ and $g(x)$ is less than $\epsilon$ for all $x$. Hence a continuous map $f: \mathbb{S}^{k} \to M$ can be approximated by a smooth map $g$. Moreover, $f$ and $g$ are homotopic, as there exists a continuous deformation (homotopy) from $f$ to $g$. This homotopy essentially ‘smoothens’ out the irregularities in $f$ to transition it into the smooth map $g$.

Hence we may assume that $f (\mathbb{S}^{k})$ does not cover all of $\mathbb{S}^{n}$ when $k < n$. Suppose then the south pole is not covered, then we can push the image from the south pole, we can push the entire image to the north pole. We have deformed the map into a constant map. Thus

\[\pi_ {k}(\mathbb{S}^{n}) =0 \text{ if } k<n.\]Consider the case $k=n$. We know that homotopic maps of an $n$-sphere into itself have the same degree. A theorem of Heinz Hopf says in fact that maps of any connected, closed, orientable $n$-manifold $M$ into an $n$-sphere $\mathbb{S}^{n}$ are homotopic if and only if they have the same degree (the proof is nontrivial). Thus

\[\pi_ {n}(\mathbb{S}^{n}) = \mathbb{Z}.\]Exact Sequences of Groups

A sequence of groups and homomorphisms

\[\dots \to F \xrightarrow{f} G \xrightarrow{g} H \to \dots\]are said to be exact at $G$ if the kernel of $G$ coincides with the image of $f$,

In particular, we must have that the composition $g\,\circ\,f$ is the trivial homeomorphism sending all of $F$ into the identity element of $H$. The entire sequence is said to be exact if it is exact at each group. $0$ will denote the group consisting of just the identity (if the groups are not abelian we usually use $1$ instead of $0$).

Some Examples.

If

\[0\xrightarrow{f} H \xrightarrow{g} G\]is exact at $H$ then the image of $f$ coincides with the kernel of $g$. However the image of $0$ is the identity in $H$ alone, it means that the kernel of $g$ is the identity, nothing else. Then $g$ is injective, namely $1:1$. And since $g$ is $1:1$, we may identify $H$ with its image; in other words, we may consider $H$ to be a subgroup of $G$! We would simply write

\[0 \to H \xrightarrow{g} G.\]If

\[H\xrightarrow{h}G\xrightarrow{g} 0\]is exact then the image of $h$ is the kernel of $g$, which is the whole $G$. So $h$ is onto. Again we would forget about $g$.

If

\[0 \to G\xrightarrow{h}H \to{}0\]is exact, $h$ is both $1:1$ and onto, then $G \cong H$.

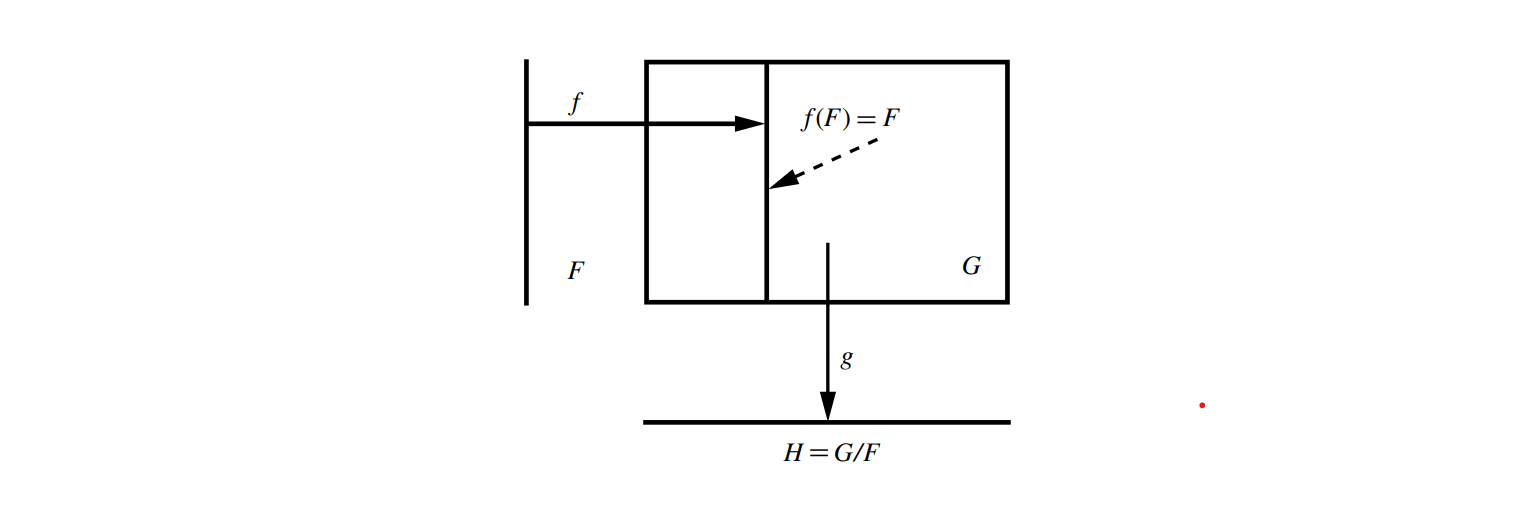

Consider an exact sequence of three nontrivial abelian groups, the so-called short exact sequence \(0 \to F \xrightarrow{f}G \xrightarrow{g}H \to 0\)

then the kernel of $g$ is the image of $f$, which is considered the subgroup of $G$,

\[F \cong f(F) \subset G\]and $g$ is onto. Then

\[H \cong \frac{G}{F}.\]

If the homomorphisms involved are understood, we frequently will omit them. For example, the exact sequence

\[0 \to 2 \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{Z}_ {2} \to 0\]says that the even integers form a subgroup of the integers and

\[\mathbb{Z}_ {2} \cong \mathbb{Z} / 2\mathbb{Z}.\]The exact sequence

\[0 \to \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{S}^{1} \to 0\]where $\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{S}^{1}$ is the exponential homomorphism

\[r\in \mathbb{R} \mapsto \exp(i 2\pi r)\]onto the unit circle in the complex plane. Then the circle is a coset space

\[\mathbb{R}^{1} \cong \mathbb{R} / \mathbb{Z}.\]In brief, a short exact sequence of abelian groups is always of the form

\(0 \to H \to G \to G / H \to 0.\)

The Homotopy Sequence of a Bundle

For simplicity only, we shall consider a fiber bundle with connected fiber and base.

Theorem. If the fiber $F$ is connected, we have the exact sequence of homotopy groups

\(\dots \to \pi_ {k}(F)\to \pi_ {k}(P)\to \pi_ {k}(M)\xrightarrow{\partial} \pi_ {k-1}(F)\to\dots\) \(\dots \xrightarrow{\partial}\pi_ {1}(F) \to\pi_ {1}(P) \to\pi_ {1}(M)\to 1\)

The homomorphism from $\pi(F)$ to $\pi(P)$ is defined by the induced map of the inclusion map $i: F \to P$. It should be clear that a continuous map $f: V \to M$ that sends base points into base points will induce a homomorphism $f_ {\star}: \pi (V)\to \pi(M)$, since a sphere that gets mapped into $V$ can then be sent into $M$ by $f$. The map from $\pi(P)$ to $\pi(M)$ is the induced map of $\pi$ the projection. The remaining boundary homomorphism

is illustrated in the following figure for the case $k=2$.

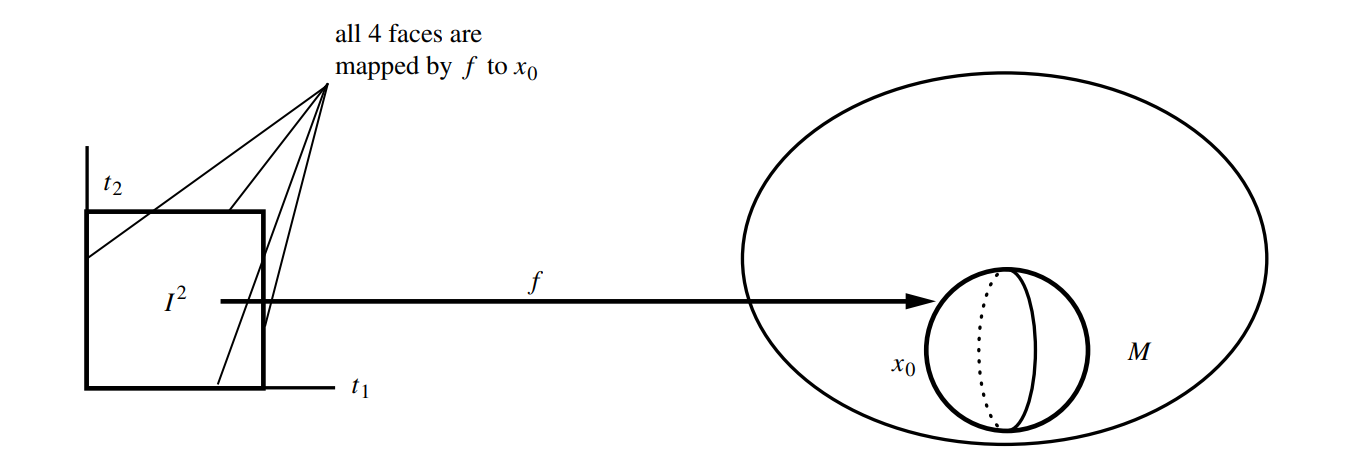

Consider $f:\mathbb{S}^{2} \to M$, defining an element of $\pi_ {2}(M)$. The entire boundary is mapped to $x_ {0}$.

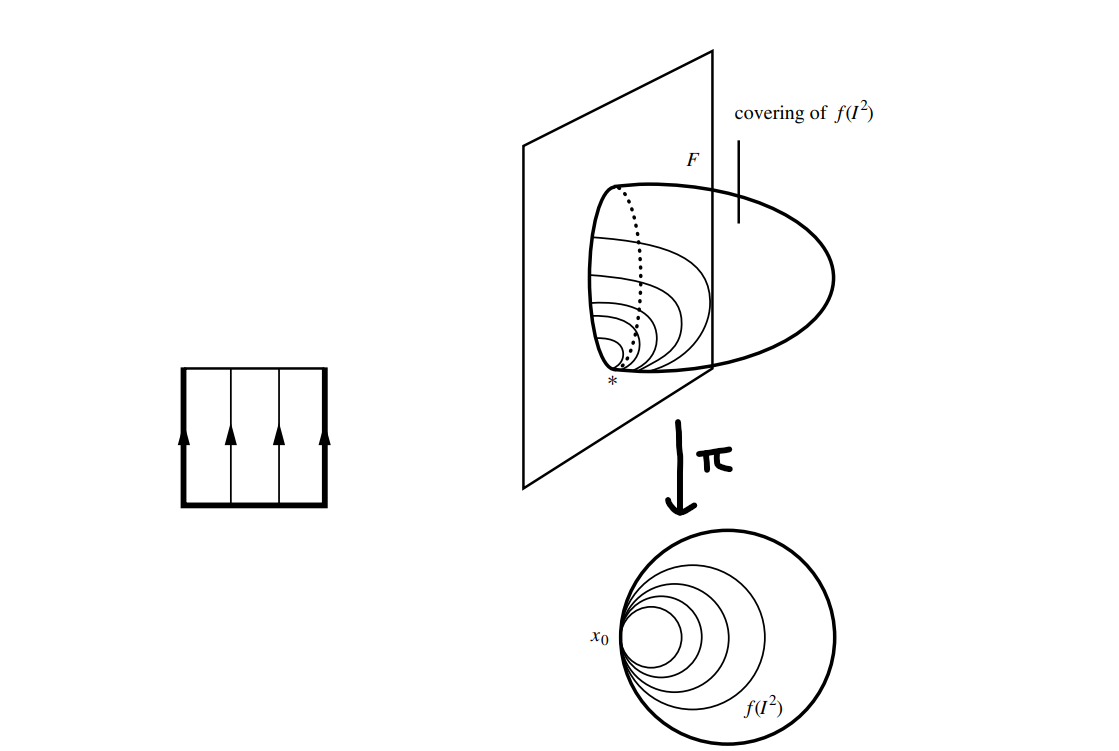

Consider the homotopy cover of $f(\mathbb{I}^{2})$ on the bundle $P$.

The above figure shows our assignment

\[\partial: \pi_ {2}(M) \to \pi_ {1}(F).\]Briefly speaking, the lift of a $k$-sphere in $M$ yields a $k$-disc in $P$ whose boundary is a $(k − 1)$-sphere in $F$.

We shall not prove exactness. Just mention that at the last stage, $\pi_ {1}(P)\to \pi_ {1}(M)$ is onto because $F$ has been assumed connected. A circle on $M$ can be lifted to a curve in $P$ whose endpoints lie in $F$ and since $F$ is connected, these endpoints can be joined in $F$ to yield a closed curve in $P$ that projects down to the original circle.

The Relation Between Homotopy and Homology Groups

Let $\pi_ {1}(M)$ be the fundamental group of a connected manifold $M$, we know that this group is not always abelian. A good example of this is the so-called figure-eight space, also known as the wedge sum of two circles, where the fundamental group $\pi_1$ is not abelian. The figure-eight space can be visualized as two circles touching at a single point. Let’s denote these circles as $A$ and $B$, and the point where they meet as $x_0$. The fundamental group of the figure-eight space is generated by two loops: one that goes around circle $A$ and returns to $x_0$, and another that goes around circle $B$ and returns to $x_0$. We can denote these loops as $a$ and $b$, respectively. To show that this group is not abelian, we need to demonstrate that the order in which you traverse $a$ and $b$ matters. Specifically, we need to show that $ab$ is not homotopic to $ba$, where $ab$ represents traversing loop $a$ followed by loop $b$, and $ba$ represents traversing $b$ followed by $a$. Loop $ab$ first goes around $A$ and then around circle $B$. Loop $ba$ first goes around circle $B$ and then around circle $A$. The way these loops are concatenated makes a difference. Since these loops cannot be continuously deformed into each other without breaking and rejoining at $x_0$, they represent different elements in the fundamental group. The fundamental group $\pi_1(\text{Figure-Eight}, x_0)$ is actually isomorphic to the free group on two generators, denoted $F(a, b)$. In a free group, the generators $a$ and $b$ (and their inverses) can be combined in any sequence, but there is no relation like $ab = ba$ to simplify that sequence. Therefore, the group is non-abelian.

The key point here is that the paths $ab$ and $ba$ cannot be homotopically deformed into each other within the space of the figure-eight, making the fundamental group non-abelian.

Let $[\pi_ {1},\pi_ {1}]$ be the subgroup of $\pi_ {1}$ generated by commutators (elements of form $bab^{-1}a^{-1}$). Then the quotient group

\[\frac{\pi_ {1}}{[\pi_ {1},\pi_ {1}]} \cong H_ {1}(M,\mathbb{Z})\]where $H_ {1}(M,\mathbb{Z})$ is the first homology group.

For the higher homotopy groups we have the Hurewicz theorem (Hurewicz was the inventor of these groups):

For the higher homotopy groups we have the Hurewicz theorem (Hurewicz was the inventor of these groups), which predicts the first non-vanishing homology group from the first non-vanishing homotopy group, and vise versa.

Theorem. Let $M$ be simply connected, $\pi_ {1}=0$. Let $\pi_ {j}$ be the first non-vanishing homotopy group. Then $H_ {j}(m;\mathbb{Z})$ is the first non-vanishing homology group and those two groups are isomorphic,

\[\pi_ {j}(M) \cong H_ {j}(M;\mathbb{Z}).\]The proof is difficult, we will just mention an example. We know $\mathbb{S}^{n}$ is simply connected for $n>1$. Also, we know $H_ {j}(\mathbb{S}^{n};\mathbb{Z})$ is zero for $j<n$, and $H_ {n}(\mathbb{S}^{n};\mathbb{Z})\cong\mathbb{Z}$. Thus

\[\pi_ {j}(\mathbb{S}^{n}) = 0,\quad j<n\]and

\[\pi_ {n}(\mathbb{S}^{n})\cong \mathbb{Z}.\]Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: