Symmetry Groupoid

Some group theory

Mathematically, a symmetry of a set $S$ is a transformation that preserves it. All the symmetry transformations naturally form a group. It would be helpful to review some basic definitions of group theory here. A subgroup $H$ of $G$ is denoted $H<G$, if $H$ is a normal subgroup, meaning $GHG^{-1}=H$, then $H$ is denoted by $H\lhd G$. Given two groups $H,K$, the simplest way to construct a new group containing $H$ and $K$ as subgroup is by the means of direct product, $H\times K$. The elements of $H\otimes K$ are $(h,k)$ with multiplication given by

The copy of $H$ in $H\times K$ is simply $(H,1)$ and the copy of $K$ in $H\times K$ is $(1,K)$.

We have the “recognition theorem” saying that if 1) $G$ can be written as form $hk$ and 2) $H\cap K$ is trivial and 3) elements in the copy of $H$ commutes with that in $K$ then we can write $G$ as a product of $H$ and $K$. However the last condition is not necessary for $G$ to be written as a direct multiplication of $H$ and $K$.

Let $H,K$ be subgroups of $G$, the direct product $H\times K$ is not guaranteed to be a subgroup of $G$. It is because $h^{-1}kh$, the conjugate of $k$, may not be in $K$ again. If so, $K$ is a normal subgroup. The claim is that $K\times H$ is only a subgroup if one of them is a normal subgroup, for example if $K\lhd G$. How can we come up with a modified version of multiplication such that $H$ and $K$ always gives a group.

Consider two groups $H,K$ not initially in a common group. Suppose $K$ defines an automorphism (which is isomorphism on itself) on $H$, that is, each element $k$ of $K$ defines an automorphism $\phi_ {k}$ on $H$. In other words, we have

\[\phi: K\to \text{Aut}(H),\quad k\mapsto \phi_ {k}.\]Definition. For two groups $H$ and $K$ and an action $\phi: K\to \text{Aut}(H)$ of $K$ on $H$ by automorphisms, the corresponding semidirect product $H\rtimes K$ is defined as follows: as a set it is

\[\left\{ (h,k) \,\middle\vert\, h\in H,k\in K \right\}.\]The group law on $H\rtimes K$ is

\[(h_ {1},k_ {1})(h_ {2},k_ {2}):=(h_ {1}\phi_ {k}(h_ {2}),k_ {1}k_ {2}).\]The notation in $\rtimes$ has a small $\lhd$ in it, suggesting $H$ (or more precisely, the copy of $H$ in $H\rtimes K$) is a normal subgroup of $H\rtimes K$ whose elements are $(h,1)$. In some convention for semidirect product notation, the group being acted on always goes first in $H\rtimes K$, and the group doing the acting goes second. If we reversed this then the notation could be $K\ltimes H$ so the arrow still points to the normal subgroup.

Symmetry groupoids

The symmetry represented by group action are in a sense global (don’t confuse this with global and local gauge theory, which are both depicted by group actions), the symmetries of a structure (geometric or otherwise) always involve the whole structure. To be specific, a global symmetry is one that holds at all points of the spacetime, whereas a local symmetry is one with a different symmetry transformation at different points of the spacetime, that is, a local symmetry transformation is parametrized by the spacetime coordinates. Mathematicians have a local theory of symmetry, which is known as the theory of groupoids.

The convention is usually that, if a symmetry acts on the space(-time) coordinates, then it is called spacetime symmetry, if not a local symmetry. Rotation is a spacetime symmetry while the gauge transformation is local. The familiar local gauge symmetry (gauge redundancy) is an example of local internal symmetry. But the local gauge symmetry can be regarded as a redundancy when describing the system thus not a symmetry at all. It is more like the equation of motions admits a class of solutions, any two elements in the solution class differ by a gauge transformation.

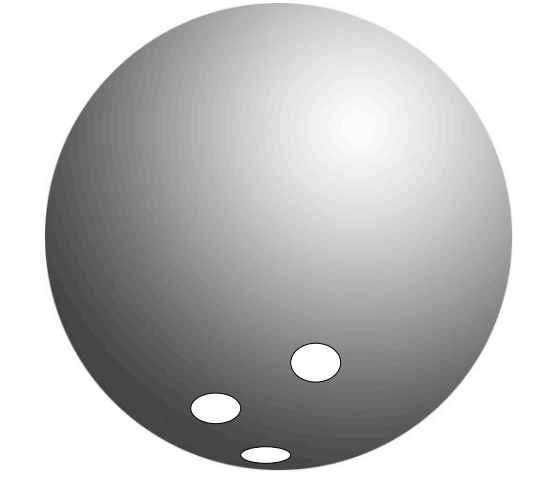

As an example of a different (from local gauge transformation) kink of local transformation, look at a two-sphere $\mathbb{S}^{2}$. It is a maximal symmetric space, got all the symmetries you can think of, rotation, reflection, etc. Now, imagine we drill three holes on the two sphere, as shown in the figure below.

The three holes will mess up the symmetry of the $\mathbb{S}^{2}$ seriously, the only symmetry left now is the trivial one! However, if we look locally at points far from the holes, at least for small transformation, these points are not concerned about the holes far far away so some kind of “local” symmetry should still hold. Mathematically, denote the punctured $\mathbb{S}^{2}$ as a manifold $X$, the transformation $g$, then we can construct the direct product $X\times G$ where $G$ is the isometry group of $\mathbb{S}^{2}$. Let the elements of $X\times G$ be $R=(x,g)$, then $g$ can act on $x$ in the usual way. The problem is that $gx$ may not be in $X$ anymore, so we only consider pairs $(x,g)$ such that $gp$ is still in $X$. Then we can study the algebraic property of the set of $R$. For more details of this simple example, refer to the introductory paper by Angelo Vistoli.

The groupoid is usually defined to be a category where every arrow has an inverse. The usual group is just a groupoid with one object. In our context, a groupoid will assign to any two objects $m_ {0}, m_ {1} ∈ M$ a collection (possibly empty) of arrows from $m_ {1}$ to $m_ {0}$. the $m_ {0,1}$ are like objects and $M$ a Category. These arrows are thought of as ‘symmetries’, but in contrast to Lie group actions this symmetry need not be defined for all $m\in M$ – only pointwise. This corresponds to the state that not all pairs of objects need to have arrows. On the other hand, we require that the collection of all such arrows (with arbitrary end points) fit together smoothly to define a manifold, and that arrows can be composed provided the end point (target) of one arrow is the starting point (source) of the next. This reminds us of group structure.

The following note is taken from this paper, including (some of) the notations. As an simple example, consider the tiling of the (infinite) Euclidean $\mathbb{R}^{2}$ by identical $2\times 1$ rectangles, specified by the set $X$ (idealized as 1-dimensional) where the grout between the tiles lies. To be specific, denote the horizontal grouts $H=(\mathbb{R},\mathbb{Z})$ and vertical grouts $V=(2\mathbb{Z},\mathbb{R})$, then $X=H\cup V$. The set of identical tiles is $\mathbb{R}^{2}-X$. The symmetry group of $X$ is denoted $G$, consisting of rigid translations, reflections and rotations. The normal subgroup of $G$ is the translation group. The lattice $\Lambda$ consists of the corner points of the tiles, $\Lambda=H\cap V=2\mathbb{Z}\times\mathbb{Z}$.

Although the symmetry greatly constraints the space, there is something lost when going from the tiling of $\mathbb{R}^{2}$ to the symmetry group $G$,

- both $X$ and $\Lambda$ satisfy the same symmetry group $G$, even though they describe very different things, even the dimension is different;

- $G$ contains no local details of the tiling, for example we could fill any color pattern that is symmetric under $G$;

- If the size of $\mathbb{R}^{2}$ is finite, for example if we were tiling the bathroom floor, then the symmetry group shrinks greatly since most of the original symmetries, such as translation, will move the entire floor thus no longer a symmetry. However a repetition pattern of the floor is clearly visible, we say locally it is still the same tiling.

Our first groupoid will enable us to describe the symmetry of the finite tiled rectangle. We first define the transformation groupoid of the action of $G$ on $\mathbb{R}^{2}$ to be the set

\[\mathcal{G}(G,\mathbb{R}^{2}):= \left\{ (x,g,y) \,\middle\vert\, x,y\in \mathbb{R}^{2},g\in G,x=gy \right\} .\]We used script $\mathcal{G}$ to remind us that $\mathcal{G}$ can be regarded as a (small) category, since in our convention we use script capital letters such as $\mathcal{A},\mathcal{B}$ to denote categories.

The philosophy is similar to what we talked about in the punctured two-sphere case, if the old group does not work in the new situation then construct a new thing that includes both the group and the space the group acts on. Only it is not enough to just include one point in the space, we in fact need two, one serve as as source and one target. With $\mathcal{G}(G,\mathbb{R}^{2})$ we have the partially defined binary operation

\[(x,g_ {1},y)\times (y,g_ {2},z) = (x,g_ {1}g_ {2},z).\]For each element $\overline{g}\in\mathcal{G}$, there automatically exists two functions, source and target, denoted $s(-)$ and $t(-)$ respectively. The group action takes the source to the target. For example, let $\overline{g}=(x,g,y)$ then $s(g)=y$ and $t(g) = x$. The binary operation has following properties.

- The binary operation is partially defined, for two elements $\overline{g},\overline{h}\in\mathcal{G}$, $\overline{g}\overline{h}$ is defined iff $t(\overline{h})=s(\overline{g})$.

- It is associative, $(\overline{a}\overline{b})\overline{c}=\overline{a}(\overline{b}\overline{c})$.

- For each $\overline{g}\in\mathcal{G}$, there exist left and right identity $\mathbb{1}_ {\text{left}}\,\overline{g}=\overline{g}\,\mathbb{1}_ {\text{right}}=g$.

- each $\overline{g}$ has an inverse $g^{-1}$ such that $g g^{-1}=\mathbb{1}_ {\text{left}}$ and $g^{-1}g=\mathbb{1}_ {\text{right}}$.

In general, a groupoid $\mathcal{G}$ with base $B$ is the collection $\mathcal{G}$ with two arrows source $s$ and target $t$, and partially defined binary operation satisfying the four conditions above. We may think of each element of $\mathcal{G}$ as arrows pointing from one element of $B$ to another. In the language of category theory, this is a groupoid with objects identified as elements of the base $B$, so a category of the base. We have

Let $B=[0,2m]\times[0,n]$ be a finite subset of $\mathbb{R}^{2}$. The restriction of $\mathcal{G}(G,\mathbb{R}^{2})$ to $B$ is defined (naturally) to be

\[\mathcal{G}{\Large\mid}_ {B}:=\left\{ \overline{g}\in \mathcal{G} \,\middle\vert\, s(\overline{g})\in B,t(\overline{g})\in B \right\} .\]The following concepts from groupoid theory, applied to this example, now show that $\mathcal{G}{\Large\mid}_ {B}$ indeed captures the symmetry which we see in the tiled floor.

- An

orbitof groupoid $\mathcal{G}$ over $B$ is an equivalence class for the relation

This is just a direct generalization to orbits in group theory.

- The

isometry groupof $x\in B$ consists of $\overline{g}\in\mathcal{G}$ with $s(\overline{g})=t(\overline{g})=x$.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: