Domain Wall

1. Kink in 1+1 dimension

Domain walls in theoretical physics are fascinating phenomena that arise in a variety of contexts, from condensed matter physics to cosmology. They are a type of topological soliton that occurs when a discrete symmetry is spontaneously broken. In simpler terms, domain walls can be thought of as boundaries between different phases or domains where the order parameter (some scalar degree of freedom) differs on either side.

When kink solutions are placed in more than one spatial dimension, they become extended planar structures called “domain walls.” For example, in $3+1$ dimension, a flat $\mathcal{Z}_ {2}$ domain wall in $yz$-plane is

\[\phi(t,x,y,z) = \eta\, \tanh\left( \sqrt{ \frac{\lambda}{2} } \, \eta x \right).\]The energy density is given by that of $\mathcal{Z}_ {2}$ kink, the our convention it reads

\[\mathcal{E} = \frac{\lambda \eta^{4}}{2} \cosh^{-4}\left( \sqrt{ \frac{\lambda}{2} } \, \eta x \right)\]since the Lagrangian is

\[\frac{1}{2} (\partial \phi)^{2} - \frac{\lambda}{4} (\phi^{2} - \eta^{2})^{2}\]and the $\mathcal{Z} _2$ kink solution (with center at $x=0$) reads

\[\phi_ {k} (x,t) = \eta \tanh\left( \sqrt{ \frac{\lambda}{2} } \eta x \right).\]The new aspects of domain walls are that they can be curved and deformations can propagate along them. Another feature of the planar domain wall is that it is invariant under boosts in the plane parallel to the wall. This is simply because the solution is independent of t, y and z and any transformations of these coordinates do not affect the solution.

The characteristic length of a kink is roughly speaking inverse to some mass, which turns out to be the mass of the fluctuating field in the kink sector $1 / \eta\sqrt{ \lambda }$. For distance scale much larger than that of a kink, we can regard it as a point particle. Recall that in the context of general relativity, the true trajectory of a particle through spacetime is such that it extremizes the proper time. In curved spacetime the trajectory (geodesic) followed by a free particle maximizes the proper time compared to nearby paths. Particles are “lazy” in the sense that they try to maximize the time spent to get to point B from point A. The action can be written as

\[S_ {1+1} = -M \int d\tau ,\]the superscript $1+1$ denotes the dimension.

The proper time is also the line element of the world line of the particle, let $X^{\mu}$ be the coordinates of the kink center, we can write

\[d\tau^{2} = g_ {\mu \nu} \left( \frac{dX^{\mu}}{dt} \right) \left( \frac{dX^{\nu}}{dt} \right) dt^{2}.\]The question is, can we derive the action Eq. (1) from the original action for $\phi$ field, of which the kink is a solution? Such a derivation should lead to Eq. (1) plus corrections that depend on the internal structure of the kink. Then Eq. (1) would be the effective action of kink.

The key assumption to derive the effective action is that, the field profile of a kink is well-approximated by that of the static kink solution in the instantaneous rest frame. Recall that, if the kink were to be given a velocity $v$, it would be Lorentz boosted to a moving frame. In that case, the instantaneous rest frame would refer to the original frame before the Lorentz boost, where the kink solution is static. Lorentz boosting the kink solution involves applying a Lorentz transformation to the coordinates, which would modify the form of kink solution $\phi_ {k}$ to account for the relativistic effects of motion, but in its own rest frame, the kink solution retains the static form given above.Generally speaking, the instantaneous rest frame of a moving object is a reference frame in which the object is at rest at a particular instant in time. This frame is also known as the object’s comoving frameor proper frame. In this frame, the laws of physics take their simplest form, just like they would in a frame where the particle was always at rest.

Let’s work in the kink frame coordinates which are denoted by $y^{a} = (\tau,\xi)$, $a=0,1$. $\tau$ is also called the kink world-line coordinate. These coordinates are functions of the background coordinates that are denoted by $x^{\mu}=(t,x)$, $\mu=0,1$. The kink world line is the world line of the kink center, denoted by $X^{\mu}=(t,X(t))$. Therefore the tangent vector to the world line is

\(T^{\mu} \propto \partial_ {t} X^{\mu} = \left( 1, V \right), \quad V:= \frac{ \partial X }{ \partial t }\) and $T$ is normalized to $T^{2}=1$.

The unit vector $\hat{N} = N^{\mu}(\tau)$ orthogonal to $\hat{T} = T^{\mu}$ is found by solving

\[g_ {\mu \nu} T^{\mu} N^{\nu} = 0, \quad N^{\mu}N_ {\mu}=N^{2} = -1.\]Note the normalization of $N$ is $-1$ since it is time-like. Since we are working in 2D, there is only one $N^{\mu}$. In the special case of a Minkowski background we choose $g_ {\mu \nu} = \eta_ {\mu \nu} = \text{diag}(1,-1)$. (This is gonna piss off some theorists I know) We find

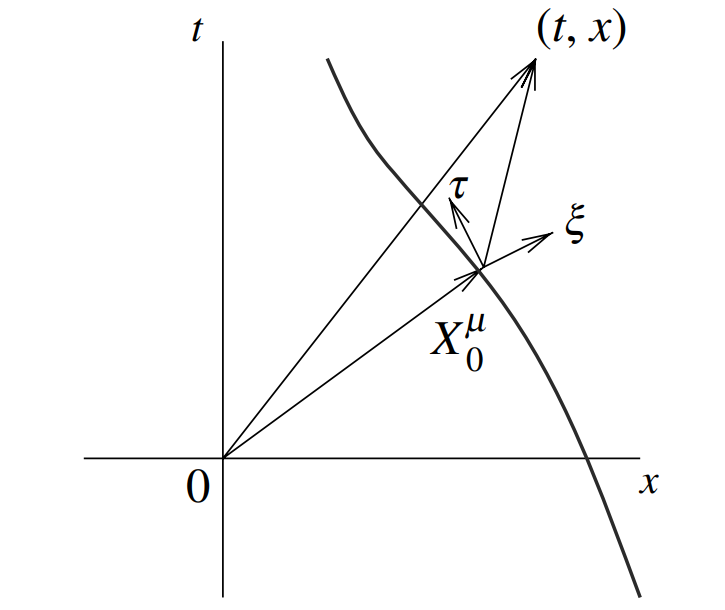

\[T^{\mu} = \gamma(1,V),\quad N^{\mu} = \gamma(V,1),\quad \gamma = \frac{1}{\sqrt{ 1-V^{2} }}.\]The coordinate axis $\tau$ is along $T^{\mu}$ and $\xi$ is along $N^{\mu}$. Therefore, if we arbitrarily choose a time $\tau_ {0}$ when the kink is located at spacetime point $X_ {0}$, then near the kink any other spacetime point coordinate can be written as

\[x^{\mu} = X_ {0}^{\mu} + \tau \hat{T}_ {0} + \xi \hat{N}_ {0},\]where $\hat{T}_ {0}$ and $\hat{N}_ {0}$ are the tangent and normal unit vector at time $\tau_ {0}$. However, we can always choose a time $\tau$ at which the coordinate in $\hat{T}$ direction is zero (at least locally), when $x^{\mu}$ is not too far away from kink world line. It is illustrated in the following figure, which I shamelessly copied from Tanmay’s textbook.

Generally speaking, given a curve $C:=p(t)$ parametrized by $t$ in manifold $\mathcal{M}$, the curve is a map from the parameter to the manifold,

\[C : \mathbb{R} \to \mathcal{M}.\]Curve $p(t)$ defines a velocity vector $\dot{p}(t)$. Note that in a general manifold (including affine space), points and vectors are distinct concepts, each serving a different role, although they are closely related and often used together in geometric computations and theoretical discussions. The tangent vector really takes a set of parametrized points and turn them into something entirely different: vectors. Furthermore, vectors can be equivalently regarded as differentials operators. The philosophy can be roughly states as: we use functions to measure the space, and we use differential to measure vectors. For example, we use coordinate patches to denote different points on a manifold, but a coordinate patch is nothing but a map from (sub-) manifold to $\mathbb{R}^{n}$, hence is a real-valued function. A vector $V$ with components $V^{0},\cdots,V^{i}$ in basis $\left\lbrace x \right\rbrace$ can be regarded as a differential operator $V = V^{i} \partial_ {i}$.

In our case, the curve $X(\tau)$ is parametrized by $\tau$, and the worldline of the kink (center) can be regarded as a coordinate curve, that is to say the tangent vector given by $\partial_ {\tau}$ is not the basis. Recall that the 2-dimensional coordinate system was defined as $y^{a}=(\tau,\xi)$, we can talk about the metric in terms of $y$’s, denoted as $h_ {ab}$, in contrast to $g_ {\mu \nu}$ in terms of $x$’s.

However, the treatment of $(\tau,\xi)$ in Vachaspati’s textbook is a little weird, it seems to regard $X^{\mu}_ {0}$ (see the figure above) as some kink of origin, which is problematic in curved manifold. Maybe I missed something here? Anyways, here I will just treat $(\tau,\xi)$ as a (locally defined) coordinate system. We can also construct basis $\partial_ {\xi}$ such that their Lie bracket is zero,

\[[\partial_ {\tau},\partial_ {\xi}]=0\]as is required for coordinate basis, this is locally equivalent to $\partial_ {\tau}$ being parallel to $\partial_ {\xi}$.

We can go on and calculate the metric in terms of $y$ coordinates. Let $\left\langle X,Y \right\rangle$ be the inner product of vectors $X$ and $Y$, we have

\[h_ {00} := \left\langle \partial_ {\tau}, \partial_ {\tau} \right\rangle = \left\langle \partial_ {\tau}X,\partial_ {\tau}X \right\rangle = \left\langle (\partial_ {\tau}X^{\mu}) \partial_ {\mu},(\partial_ {\tau}X^{\nu}) \partial_ {\nu} \right\rangle = g_ {\mu \nu} (\partial_ {\tau}X^{\mu}) (\partial_ {\tau}X^{\nu}).\]By construction we have

\[h_ {01} := \left\langle \partial_ {\tau},\partial_ {\xi} \right\rangle =0\]and

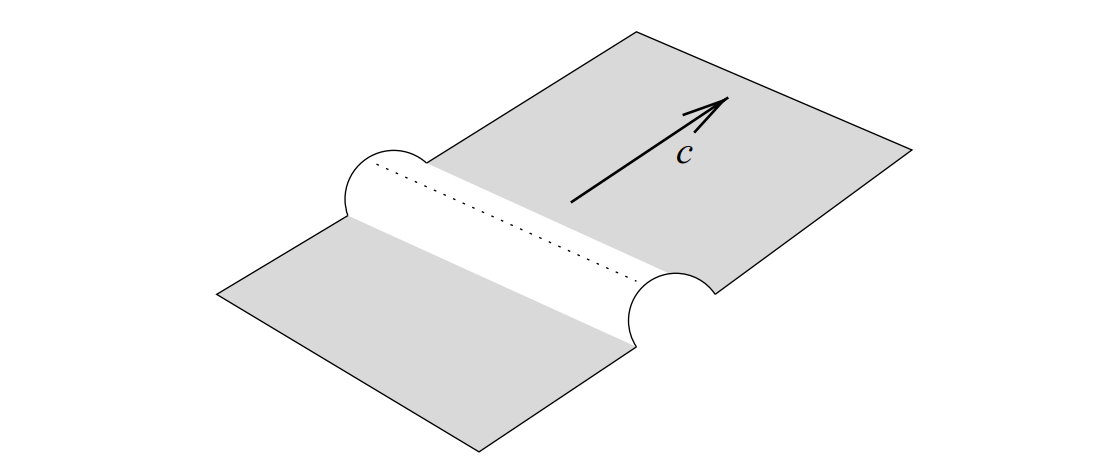

\[h_ {11} := \left\langle \partial_ {\xi},\partial_ {\xi} \right\rangle = -1.\]Next we need to write down the action. We assume the only import region is spacetime is that close to the kink world line, far from it the spacetime would be flat and the fluctuation would be a bunch of plane waves, it shouldn’t matter too much to the quantum correction of the domain wall. Thus we will only consider the action given by a “band” around the kink world line.

In the context of a curved spacetime, particularly in a two-dimensional, the action for a scalar field can be described using the general form that incorporates the effects of curvature. The action $S$ for a scalar field $\phi$ in a curved spacetime can be written as:

\[S = \int d^2x \sqrt{-g} \left( -\frac{1}{2} g^{\mu\nu} \partial_\mu \phi \partial_\nu \phi - V(\phi) + \frac{1}{2} g R \phi^2 \right)\]Here $d^2x \sqrt{-g}$ represents the invariant differential volume element in two-dimensional spacetime, $g^{\mu\nu}$ is the inverse metric tensor, used to raise indices. $g$ is a dimensionless coupling constant that describes the coupling of the scalar field to the Ricci scalar $R$, a scalar quantity that describes the curvature of spacetime and is obtained by contracting the Ricci tensor $R_{\mu\nu}$. The term $\frac{1}{2} \xi R \phi^2$ is known as the non-minimal coupling term. In two dimensions, the choice of $g$ can be particularly interesting due to the conformal properties of the spacetime. For now we will neglect the non-minimal coupling term.

In our coordinates $y=(\tau,\xi)$ and metric is $h_ {ab}$, the determinant of $h_ {ab}$ reads

\[h := \det h = - g_ {\mu \nu} \partial_ {\tau}X^{\mu} \partial_ {\tau}X^{\nu}.\]As before we want to study the effects of small fluctuation about the kink background, so we write

\[\phi = \phi_ {k} + \psi\]where $\phi_ {k}$ is the classical kink solution, $\psi$ is the deviation from it. Upon quantization we will only quantize $\psi$ not $\phi_ {k}$. The action now follows from Eq. (2),

\[\begin{align*} S &= \int d\tau d\xi \, \sqrt{ \left\lvert h \right\rvert } \mathcal{L}(\phi) \\ &= \int d\tau d\xi \, \sqrt{ \left\lvert h \right\rvert } \mathcal{L}(\phi_ {k}+\psi) \\ &= \int d\tau d\xi \, \sqrt{ \left\lvert h \right\rvert } \mathcal{L}(\phi_ {k}) + \int \frac{\delta^{2}S}{\delta \phi \delta \phi} \, \psi^{2} + \mathcal{O}(\psi^{3}) \\ &= -M_ {\text{kink}} \int d\tau \, \sqrt{ \left\lvert h \right\rvert } + \mathcal{O}(\psi^{2}). \end{align*}\]This is just we we have conjectured in Eq.(1), plus some higher order corrections! If the kink is moving relatively slowly, $\left\lvert h \right\rvert$ would be approximately $1$. Note that the negative kink mass comes from the integral

\[\int d \xi \, \mathcal{L} = \int d\xi \, (T-V) = -\int d\xi \, V =M_ {\text{kink}},\]the first order of $\psi$ disappears due to the fact that $\phi_ {k}$ is a solution to the equation of motion.

Note that the leading term in the effective action $\int d\tau$ is proportional to the world volume. This result can easily be extended to walls (and strings) propagating in higher dimensions. Even if the self-gravity of the domain wall is taken into account, the dominant contribution to the effective action is still the Nambu-Goto action.

2. Walls in 3 + 1 dimensions

In $3+1$ dimension, the position of domain wall, being a co-dimension one object in space, is described by $2+1$ dimensional coordinates. To be more specific, a domain wall in 3-dimensional space is a 2D plane, hence is parametrized by two parameters, call them $\xi^{1}$ and $\xi^{2}$. As a consequence the world-volume of such a domain wall is 2+1 dimensional hence should be parametrized by three parameters. This is reflected in how we describe the location of domain wall. Let the location of the domain wall be

\[X^{\mu} = X^{\mu}(y),\quad y = (\tau,\xi^{1},\xi^{2}),\]$\tau$ is again the proper time, $\xi^{1,2}$ are spatial coordinates. $y$ is the coordinates on the domain-wall world-volume, similar to the case in $1+1$ dimension, with metric given by

\[h_ {ab} = g_ {\mu \nu}(X) \frac{ \partial X^{\mu} }{ \partial y^{a} } \frac{ \partial X^{\nu} }{ \partial y^{b} } .\]The major difference between the kink in 1 + 1 dimensions and the domain wall is that the wall can be curved, and so the profile $\phi_ {\text{kink}}$ does not solve the equation of motion. The dynamics of a domain wall is much richer, for example, as the wall moves it accelerates and emits radiation.

The Nambu-Goto action of domain wall can be derived in the same way as in 1+1 kink,

\[S_ {0} = - \sigma \int d^{3} y \, \sqrt{ \left\lvert h \right\rvert }\]where $\sqrt{ \left\lvert h \right\rvert }$ comes from the invariant integral measure $\sqrt{ \left\lvert h \right\rvert } d^{3}y$, and $\sigma$ is the tension of the wall.

From the effective action of the domain wall Eq.(3) we can derive the equation of motion for the wall. But before that we need to know how the variation of the determinant of a matrix $h$. There are two ways to achieve that. One can calculate $\delta \det h$ directly. Under the variation $h\to h+\delta h$ where $\delta h$ is assumed to be infinitesimal, we have

\[\begin{align*} \det (h+\delta h) &= \det (h(\mathbb{1}+h^{-1} \delta h))\\ &= \det h \times \det(\mathbb{1}+h^{-1} \delta h)\\ &= \det h ( 1 + \mathrm{Tr}\,(h^{-1} \delta h) + \mathcal{O}(\delta h^{2}) )\\ &= \det h + \det h \times \mathrm{Tr}\,(h^{-1} \delta h). \end{align*}\]Hence

\[\delta \det h \equiv \det (h+\delta h)-\det(h) = \det h \times \mathrm{Tr}\,(h^{-1} \delta h).\]We just mention on the fly that there is another formula

\[\det M = \exp(\mathrm{Tr}\,\ln M).\]We could also start with this formula and arrive at the same result.

Instead of giving the full derivation of the equation of notion, we only mention here that the equation is highly non-linear since $h_ {ab}$ itself is defined as a quadratic in derivative of $X^{\mu}$.

3. Some solutions

The effective action of domain wall, or Nambu-Goto action, is valid when the domain wall is not curved too much, and separate walls (or different parts of the same wall) are not placed too closely. Otherwise the single kink solution would not be a very good approximation. In addition, in the center of mass frame, the velocity of the wall should be relatively small. If these conditions are met, we can use Nambu-Goto effective action to study the properties of walls.

Recall that we use $y^{a}, a=0,1,2$ for the parametrization of the world volume of the domain wall. (We will not dwell on the difference between parametrization and coordination here, but we should be aware.) In components $y=(\tau,\xi^{1},\xi^{2})$. The Minkowski metric is defined as $\eta=(1,-1,-1,-1)$.

A domain wall flat in $x-y$ direction is described by

\[X^{\mu} = (X^{0}=t, X^{1}=\xi^{1}, X^{2} = \xi^{2}, X^{3}=0).\]Next consider a planar domain wall with some “ripples” in $3$-direction, then $X^{3}$ is a function of $y$’s just as $X^{1}$ and $X^{2}$. Write

\[X^{\mu} = (X^{0}=t, X^{1}=\xi^{1}, X^{2} = \xi^{2}, X^{3}=X^{3}(y)).\]The metric is given by

\[h_ {ab} = \eta_ {\mu \nu} \partial_ {a}X^{\mu} \partial_ {b}X^{\nu} = \eta_ {ab} - \partial_ {a} X^{3} \partial_ {b}X^{3}\]Then we can calculate the inverse of $h_ {ab}$, insert it into the equation of motion, and solve it. Of course it is easier said then done, here we only mention some of the results. One class of solutions found by Friedlander etc. in 1976 corresponds to a pulse of arbitrary shape on a planar domain wall that propagates in the $+X^{1}$ direction at the speed of light.

These solutions are known as travelling waves.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: