Hausdorff Measure of Fractals

Background

I am writing a paper with Zhi-Peng on the Diophatine approximation,here is a short introduction on fractal as prerequisites.

A fractal, such as the middle third Cantor set, usually have the following properties:

- Self-similarity; sometimes the self similarity is not strict, it is quasi-self-similar in that arbitrarily small portions of the set can be magnified and then distorted smoothly to coincide with a large part of the set, take the Julia set for example. Or it could be ever weaker, as the statistical self-similarity for random von Koch curve.

- Has a “fine structure”. It contains details at arbitrarily small scales.

- Its fractal dimension being different from its

topological dimension(The topological dimension of a set is always an integer and is 0 if it is totally disconnected, 1 if each point has arbitrarily small neighborhoods with boundary of dimension 0, and so on). - The geometry of the fractal can not be described simply by the zero locus of some defining condition.

- The size of a fractal is usually not quantified by the usual measure, such as length, area.

In the theory of phase transition we have two notions quite similar to it:

- the system is scale-invariant at the critical point;

- there exists non-integer critical exponents at the critical point.

It seems fractal does not have a mathematically rigor definition. Kenneth Falconer mentioned in his textbook that,

My personal feeling is that the definition of a ‘fractal’ should be regarded in the same way as a biologist regards the definition of ‘life’. There is no hard and fast definition, but just a list of properties characteristic of a living thing, such as the ability to reproduce or to move or to exist to some extent independently of the environment. Most living things have most of the characteristics on the list, though there are living objects that are exceptions to each of them.

So it’s best to learn fractal by studying some examples. Two examples of fractals are:

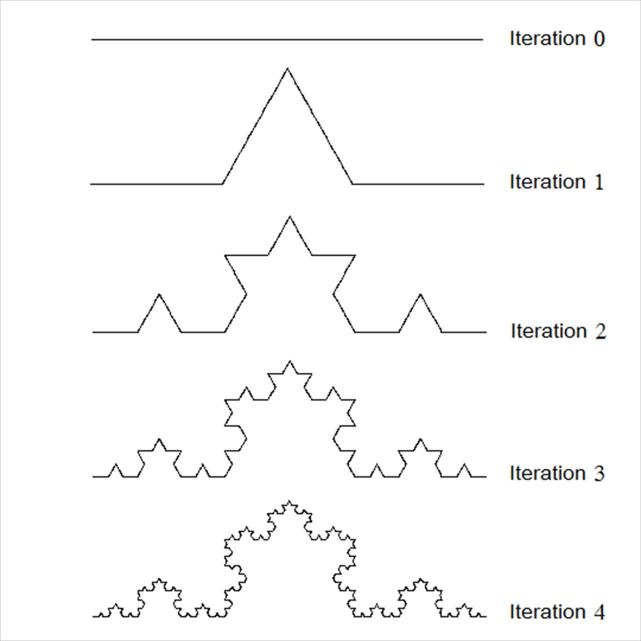

Koch's curve, obtained from a segment of a straight line, by repeating a pattern that gives the line an angle, see the figure below. It is self-similar by construction, the length goes to infinity by a power law as $n\to \infty$.

Another example is the coastal line of England, whose length $L(\epsilon)$ depends on the length $\epsilon$ of the yardstick. The coastal length is assumed to have the power law form,

\[L(\epsilon)\sim ~L_ {0}\epsilon^{-\alpha}.\]The power-law behavior reminds us with the critical exponents near the critical point in statistical field theory, for example the magnetization of a ferromagnet near the critical temperature.

We will talk more about dimension of a fractal, how to define and calculate it, in the future of the note. Now I only mention that the fractal dimension $d_ {\text{frac}}$ of the coastal line is defined to be

\[\alpha=d_ {\text{frac}}-d_ {\text{top}}\]where $d_ {\text{top}}$ is the topological dimension of the coastal line which is $1$. If the measured length does not dependent on the length of the yardstick $\epsilon$, then $\alpha=0$ and $d_ {\text{frac}}=d_ {\text{top}}$. In our case we have roughly (by actual measurement)

\[d_ {\text{frac}}\sim 1.25.\]How should we think of the dimension of a fractal? Consider some regular geometric object, such as a familiar two dimensional square $\square$. If we double the side length of it, its area is multiplied by $2^{d}$ where $d$ is the dimension. In general, if the size of an object is multiplied by a factor $\lambda$, its area, or length, or whatever quantity that measures the “content” of the object, should be multiplied by a factor $\lambda^{d}$, where $d$ can be regarded as (one of the many) definitions of dimension. The number obtained in this way is usually referred to as the similarity dimension of the set.

Let’s try to apply this definition to Koch’s curve. It is self-similar, if we shrink it by a factor of $3$, then it reduces to one of its four “components”. This component should have length that is one quarter of the original one. In other words, if we multiply Koch’s curve by factor $\lambda=\frac{1}{3}$, then the length should be multiplied by $\frac{1}{4}$, the before-mentioned definition of dimension should give

\[\text{new length}=\text{new size}^{d}\implies \frac{1}{4}=\left( \frac{1}{3} \right)^{d}\implies d\sim 1.26.\]However, similarity dimension can not be applied to fractals which lack strict self similarity. There are other definitions of dimension that are much more widely applicable, such the famous Hausdorff dimension (which will be the central idea of the note), or box-counting dimension. Very roughly, a dimension provides a description of how much space a set fills. It is a measure of the prominence of the irregularities of a set when viewed at very small scales.

There exists various different definitions of dimension of a fractal, and applied on the same set they give different results. However, when applied on a perfectly self-similar fractal, such as the Koch’s curve, they should all give the same result.

The fractal dimension is used to quantify this roughness and complexity. The higher the dimension, the higher the roughness, the higher the complexity. The fractional dimension not only suggests that the fractal is curved, it tells something drastically different, take the coastal line for example, it tells us the behavior of the total coastal length as the yardstick we use to measure it goes to zero.

The earliest known measure of roughness of an object is the Hausdorff dimension (also known as Hausdorff-Besicovitch dimension) introduced by Felix Hausdorff in 1918, even before fractal geometry was a thing.

Case study: Brownian motion

It seems that, in Brownian motion, the momentum change of a molecule at a collision depends only upon the last collision. It is a Gaussian stochastic process.

Consider a lattice in $D$ dimension, with space and time discretization $\Delta x$ and $\Delta t$. Supposed the molecule of study can only hop from one site to the neighbor site, with direction chosen at random. One can then ask for the probability

\[P(x_ {1},t_ {1};x_ {0},t_ {0}) = \text{molecure move from }(x_ {0},t_ {0}) \text{ to } (x_ {1},t_ {1}).\]The probability should satisfy three conditions,

- If $t_ {0}=t_ {1}$ then the particle does not move, $P=\delta(x_ {0},x_ {1})$.

- The total probability is normalized to one.

- At successive times, it can arrive only from neighbor sites.

The last conditions gives us the dynamics of the particle, it tells how the particle must move. Using the discretized Laplace operator, we can turn the last condition into an equation. Then we can go to the continuum limit by setting $\Delta t\to 0$ and $\Delta x\to 0$. This limit is well defined under the condition that $\Delta t \propto (\Delta x)^{2}$.

It shouldn’t surprise us that at the continuum limit, the probability distribution adopt a Gaussian form.

The probability satisfies the so-called Kolmogorov equation,

This will give us a path-integral interpretation of the probability.

Hausdorff Measure

For a more detailed introduction on measure theory please refer to my two previous notes, Basic Measure Theory Part I and Part II. Here we assume the basic knowledge of measure theory.

To build up some intuition, let’s return to the example of Cantor sets. If we measure it using dimension one, then it has total length zero. The set is too “small” to be measured with dimension one. However, if we measure it using dimension zero, that is just count how many points it contains, then the dimension becomes infinity. The set is too “large” to be measured with dimension zero. The question is, is there a dimension between zero and one, that we can somehow “use” to measure the size of Cantor set, which gives us neither zero nor infinity? Or, if this requirement is too strong, we can weaken it by asking if there is a number, below which the measurement gives infinity, above which the measurement gives zero, this critical point perhaps can be regarded as the dimension? Turns out, we can find such a number! That is what Hausdorff measure gives us, as we will dive into details.

The idea behind the Hausdorff dimension is to measure how a set scales as you cover it with balls of decreasing radius. In more technical terms, it quantifies how the number of these small balls (or other shapes) needed to cover the set scales as the size of the balls decreases. So first, we need to define how to cover a set in rigorous mathematical language.

Recall that if $U$ is a subset of $\mathbb{R}^{n}$ (or any other metric space), then the diameter of $U$, denoted $\left\lvert U \right\rvert$, is defined to be the greatest distance between any two points in it, that is

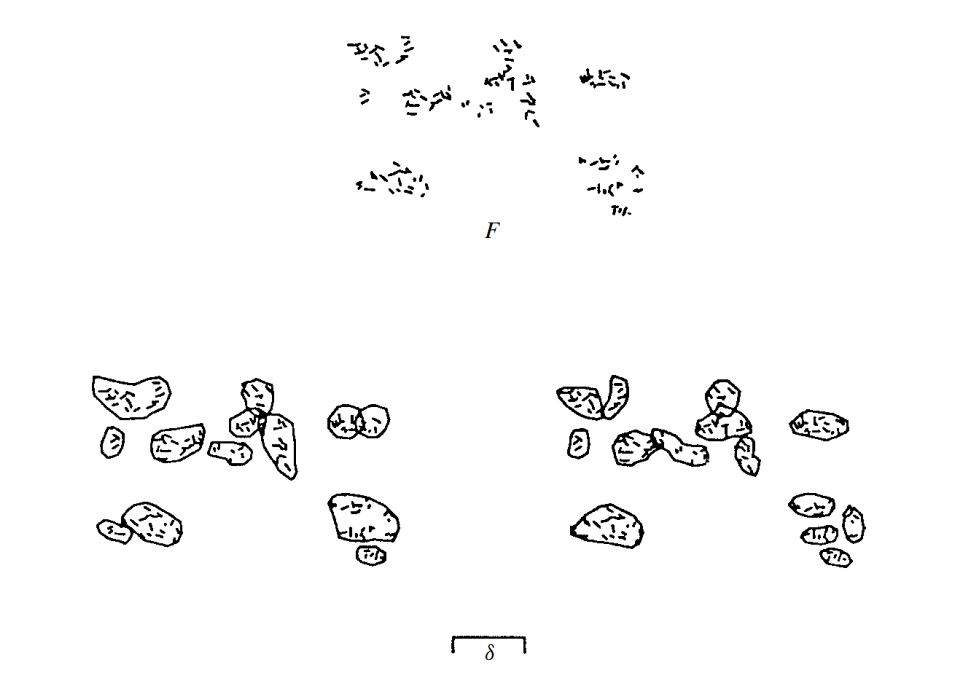

If $\left\lbrace U_ {i} \right\rbrace$ is a countable (or finite) collection of sets of diameter at most $\delta$, that is $\left\lvert U_ {i} \right\rvert\leq \delta$. If $\left\lbrace U_ {i} \right\rbrace$ covers $F$, i.e.

\[F \subset \bigcup_ {i} U_ {i} ,\]Then $\left\lbrace U_ {i} \right\rbrace$ is said to be a $\delta$-cover of $F$.

Let $F$ be the subset of $\mathbb{R}^{n}$, we introduce a non-negative number $s$ which will play the role of dimension in the future. For any diameter $\delta>0$ we define

\[\mathcal{H}^{s}_ {\delta}(F) := \text{inf } \left\lbrace \sum\left\lvert U_ {i} \right\rvert ^{s} \,\middle\vert\, \left\lbrace U_ {i} \right\rbrace \text{ is a } \delta \text{-cover of } F \right\rbrace .\]Thus we look at all the $\delta$-cover of $F$ and seek to minimize the sum of the $s$th powers of the diameters. This sum goes to a limit as $\delta$ goes to zero, we define

\[\mathcal{H}^{s}(F) := \lim_ { \delta \to 0 } \mathcal{H}_ {\delta}^{s}(F).\]The limit always exists for any set $F$, but it need not be any finite number, it can (and usually is) $0$ or $\infty$. We call $\mathcal{H}^{s}(F)$ the $s$-dimensional Hausdorff measure of $F$

To show that $\mathcal{H}^{s}$ is indeed a measure, we must show that it satisfies all the properties a measure must have, for example $\mathcal{H}^{s}(\emptyset)$ is zero, the measure of a subset is always no larger than the original set, etc. We will not provide a proof here.

Hausdorff measure is a generalization of more familiar measures, such as length, area and volume. Specifically, it can be shown that for a Borel subset $F$ of $\mathbb{R}^{n}$, $\mathcal{H}^{s}(F)$ is equal to its Lebesgue measure, namely $n$-volume up to a multiplicative constant,

\[\mathcal{H}^{n}(F) = c_ {n}^{-1} \text{vol}^{n(F)},\]where $c_ {n}$ is the volume of an $n$-dimensional ball if diameter $1$.

Similarly, for a nice lower dimensional subset of $\mathbb{R}^{n}$, we have that $\mathcal{H}^{0}$ is the number of points in $F$, $\mathcal{H}^{1}$ is the length of a smooth curve $F$, $\mathcal{H}^{2}$ is $\frac{1}{\pi}$ times the area of $F$, etc.

We know that one of the defining concept of dimension is revealed under scaling of a subset. On magnification by a scale $\lambda$, the length of a curve is multiplied by $\lambda$, the area of a surface is multiplied by $\lambda^{2}$, the volume of an object is multiplied by $\lambda^{3}$. If Hausdorff measure is truly a generalization of length, area and volume, then $s$-Hausdorff measure should be multiplied by $\lambda^{s}$. It turns out to be true.

Scaling Property. Let $S$ be a similarity transformation of scale factor $\lambda>0$. If $F\subset \mathbb{R}^{n}$, then

\[\boxed{ \mathcal{H}^{s}(S(F)) = \lambda^{s}\mathcal{H}^{s}(F). }\]Proof. The similarity transformation $S$ also transfers a $\delta$-cover of $F$ to a $\lambda \delta$-cover of $S(F)$, for everything is scaled by a factor of $\lambda$. By definition of Hausdorff measure we have, after the scaling,

\[\mathcal{H}^{s}_ {\lambda \cdot\delta}(SF) = \text{inf}\left\lbrace \sum \left\lvert A_ {i} \right\rvert^{s} \mid A_ {i} \text{ is a }\lambda \delta \text{ cover of }SF \right\rbrace\]and I claim that each element $A_ {i}$ of $\lambda \delta$-covers of $SF$ is obtained by $\lambda U_ {i}$ for a unique $U_ {i}$ which is a $\delta$-cover of $F$. Roughly speaking, it is because 1) each $\delta$-cover of $F$ gives a $\lambda\delta$-cover of $SF$, it means that $S$ is an injection; 2) since $\lambda \neq 0$, there always exists an inverse scaling map $S^{-1}$ which scales $SF$ back to $F$, i.e. scaling by $\lambda ^{-1}$, $S^{-1}$ is also an injection just like $S$, since they are essentially the same kind of operation; 3) since $S$ and $S^{-1}$ are both injections, $S$ is a bijection. And their measures, $\mathcal{H}^{s}_ {\lambda \delta}(A_ {i})$ and $\mathcal{H}^{s}_ {\delta}(U_ {i})$ where $A_ {i}=SU_ {i}$ differs only by a multiplicative constant, which turns out to be $\lambda^{s}$, as we will see later. It means that $S$ preserves the order, if $U\leq U’$ then $\sum\left\lvert SU \right\rvert^{s}\leq \sum\left\lvert SU’ \right\rvert^{s}$. Thus all the $A_ {i}$s and all the $U_ {i}$s (and their Hausdorff measures) are 1-2-1 correspondent, with the ordering preserved. Then we have

\[\begin{align*} \mathcal{H}^{s}_ {\lambda \cdot\delta}(SF) &= \text{inf }\left\lbrace \sum \left\lvert A_ {i} \right\rvert^{s} \right\rbrace = \text{inf }\left\lbrace \sum \left\lvert SU_ {i} \right\rvert^{s} \right\rbrace \\ &= \text{inf }\left\lbrace \lambda^{s} \sum \left\lvert U_ {i} \right\rvert^{s} \right\rbrace = \lambda^{s}\mathcal{H}^{s}_ {\delta}(F), \end{align*}\]where $\left\lbrace U_ {i} \right\rbrace$ is a $\delta$-cover of $F$ thus $\left\lbrace SU_ {i} \right\rbrace$ is a $\lambda\delta$-cover of $S(F)$. On taking the limit $\delta\to 0$ we have

\[\mathcal{H}^{s}(SF) = \lambda^{s}\mathcal{H}^{s}(F).\]Q.E.D.

Note that the proof here is slightly different than what Falconer gave in his textbook. There to prove $\text{inf}\left\lbrace A \right\rbrace=\text{inf}\left\lbrace B \right\rbrace$ he essentially proves that 1) $\text{inf}\left\lbrace A \right\rbrace\leq \text{inf}\left\lbrace B \right\rbrace$ and 2) $\text{inf}\left\lbrace A \right\rbrace\geq \text{inf}\left\lbrace B \right\rbrace$, then it follows $\text{inf}\left\lbrace A \right\rbrace=\text{inf}\left\lbrace B \right\rbrace$. Our proof is a little big different, it says that 1) $S:A\to B$ is a injection and 2) $S^{-1} B\to A$ is also an injection, so $S$ is a bijection. Furthermore, $S$ preserves the ordering, so $\text{inf}\left\lbrace A \right\rbrace=\text{inf}\left\lbrace B \right\rbrace$.

A similar argument gives the following result. Let $F\subset\mathbb{R}^{n}$ and $f: F\to \mathbb{R}^{m}$ be a map such that

\[\left\lvert f(x)-f(y) \right\rvert \leq c\left\lvert x-y \right\rvert ^{\alpha}, \quad c,\alpha>0.\]Which is called the Holder condition of exponent $\alpha$. Then for each $s$

Particularly important is the case $\alpha=1$, when the map is called Lipschitz. This case can be used to prove that $\mathcal{H}^{s}$ is translational and rotational invariant, we will not go to the details though.

Hausdorff Dimension

The notion of dimension is central to fractal geometry. Roughly speaking, dimension indicates how much space a set occupies near to each of its points. The keyword here is near, dimension, when interpreted in this way, is a local notion, not global. The global size a set occupies might has nothing to do with dimension, for example, given two different line segments, one is longer than the other hence occupies more space, but they are both dimension one, and length is the global size. On the other hand, if you pick a point and look at what happens in its small neighbor, then these two lines appears the same. That is to say, the local size of these to lines are the same, reflecting the fact that they are of the same dimension.

Of the wide variety of “fractal dimensions” in use, the Hausdorff dimension is the oldest and probably the most important. It has the advantage of being defined for any set, not just strictly self-similar ones. It is also mathematically convenient, as it is based on measures, which are relatively easy to manipulate. However, a major disadvantage is that it can be sometimes hard to calculate by numerical methods.

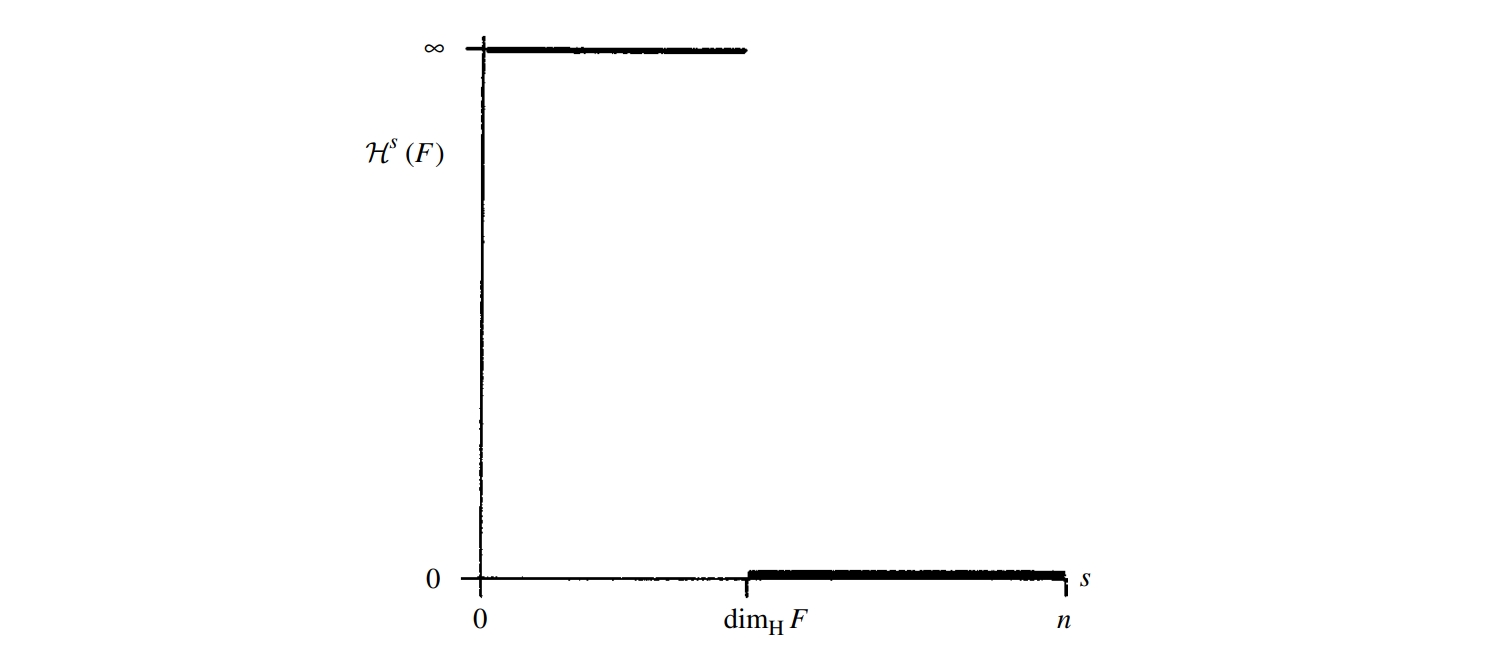

The graph of Hausdorff measure $\mathcal{H}^{s}$ vs $s$ is shown below. Below the critical value it is infinity, above the critical value it is zero, at the critical point it jumps from $\infty$ to $0$. We define this critical value as the Hausdorff dimension, denoted $\text{dim}_ {H}$. It is also called Hausdorff-Besicovitch dimension. The Hausdorff dimension of a set $F$ is denoted $\text{dim}_ {H}F$. We state without proof that, Hausdorff dimension exists for any subset of $\mathbb{R}^{n}$.

Formally,

\[\mathcal{H}^{s}F = \begin{cases} \infty & 0\leq s < \text{dim}_ {H}F, \\ 0 & s > \text{dim}_ {H}F. \end{cases}\]If $s=\text{dim}_ {H}F$, then $\mathcal{H}^{s}F$ may be zero, $\infty$ or some finite number in between. In the last case, a Borel set satisfying this condition is called an $s$-set. Mathematically they are convenient to study and occurs surprisingly often.

Hausdorff dimension satisfies the following (rather well expected) properties.

- Monotonicity. If $E\subset F$ then $\text{dim}_ {H}E\leq \text{dim}_ {H}F$.

- Countable stability. If $F_ {1},F_ {2},\cdots$ is a sequence of countable sets, then the Hausdorff dimension of $\cup_ {i}F_ {i}$ is the supremum of $\left\lbrace \text{dim}_ {H}F_ {i} \right\rbrace$.

If follows from countable stability that if $F$ is a countable set then it has Hausdorff dimension zero.

If $F\subset\mathbb{R}^{n}$ is an open set, then $\text{dim}_ {H}F=n$, since $F$ can be covered by countable open balls, each has dimension $n$.

The Hausdorff dimension is preserved by bi-Lipschitz maps $f$, which are maps satisfy

\[c_ {1}\left\lvert x-y \right\rvert \leq \left\lvert f(x)-f(y) \right\rvert \leq c_ {2}\left\lvert x-y \right\rvert ,\]where

\[0 < c_ {1} \leq c_ {2} < \infty.\]As for the importance of bi-Lipschitz maps, I quote Falconer here:

In topology two sets are regarded as ‘the same’ if there is a homeomorphism between them. One approach to fractal geometry is to regard two sets as ‘the same’ if there is a bi-Lipschitz mapping between them. Just as topological invariants are used to distinguish between non-homeomorphic sets, we may seek parameters, including dimension, to distinguish between sets that are not bi-Lipschitz equivalent. Since bi-Lipschitz transformations are necessarily homeomorphisms, topological parameters provide a start in this direction, and Hausdorff dimension (and other definitions of dimension) provide further distinguishing characteristics between fractals.

Next let’s used the famous mid-third Cantor set as an examples to illustrate how to calculate the Hausdorff dimension.

Recall that the mid-third Cantor set $F$ (Cantor set for short) is divided into the left part and right part, each similar to the whole. Denote them as $F_ {L}$ and $F_ {R}$ respectively. It is shown in the figure below.

<div class="row mt-3">

<div class="col-sm mt-3 mt-md-0">

<figure

>

<picture>

<!-- Auto scaling with imagemagick -->

<!--

See https://www.debugbear.com/blog/responsive-images#w-descriptors-and-the-sizes-attribute and

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Learn/HTML/Multimedia_and_embedding/Responsive_images for info on defining 'sizes' for responsive images

-->

<source

class="responsive-img-srcset"

srcset="/img/fractal/CantorSet-480.webp 480w,/img/fractal/CantorSet-800.webp 800w,/img/fractal/CantorSet-1400.webp 1400w,"

sizes="95vw"

type="image/webp"

>

<img

src="/img/fractal/CantorSet.png"

class="img-fluid rounded z-depth-1"

width="100%"

height="auto"

onerror="this.onerror=null; $('.responsive-img-srcset').remove();"

>

</picture>

</figure>

</div>

</div>

<div class="caption">

Construction of the middle-third Cantor set $F$, by repeated removal of the middle third of intervals. $E_k$ is what we got after $k$th removal.

</div>

Apparently we have $\mathcal{H}^{s}(F_ {L}) = \mathcal{H}^{s}(F_ {R})$. We can find the relation between $\mathcal{H}^{s}(F)$ (the whole) and $\mathcal{H}^{s}(F_ {R})$ (the part) by noticing that, if $\left\lbrace U_ {i} \right\rbrace$ is a $\delta$-cover of $F$, then $\frac{1}{3}\left\lbrace U_ {i} \right\rbrace$ is a $\delta/3$-cover of $F_ {L}$, this gives us

\[\mathcal{H}^{s}_ {\delta/3}(F_ {L}) = \text{inf }\left\lbrace \sum_ {i}\left\lvert \frac{U_ {i}}{3} \right\rvert^{s} \right\rbrace = \frac{1}{3^{s}}\text{inf }\left\lbrace \sum_ {i}\left\lvert U_ {i} \right\rvert^{s} \right\rbrace = \frac{1}{3^{s}}\mathcal{H}^{s}_ {\delta}(F).\]Taking the limit $\delta\to0$ we have

\[\mathcal{H}^{s}(F_ {L}) = \frac{1}{3^{s}}\mathcal{H}^{s}(F).\]Also we have $F = F_ {L} \cup F_ {R}$, thus

\[\mathcal{H}^{s} (F) = \mathcal{H}^{s}(F_ {L}) + \mathcal{H}^{s}(F_ {R}) = \frac{2}{3^{s}} \mathcal{H}^{s}(F).\]The equation $\mathcal{H}^{s} (F) = \frac{2}{3^{s}} \mathcal{H}^{s}(F)$ has three solutions,

- $\mathcal{H}^{s}(F)=0$,

- $\mathcal{H}^{s}(F)=\infty$

- $0<\mathcal{H}^{s}(F)<\infty$ and $s=\log_ {3}2$.

This agrees with the picture given before, suggesting that the Hausdorff measure is infinity when the dimension is below $\log_ {3}2$, and zero above, so $\log_ {3}2$ is a critical point, hence the Hausdorff dimension of the Cantor set. However, the story is not over yet, in the last case we have assumed that $\mathcal{H}^{s}(F)$ at $s=\log_ {3}2$ is a finite quantity, which needs justification.

Recall from Fig. that $E_ {k}$ is what we got after cutting it for $k$-times. $E_ {k}$ consists of $2^{k}$ intervals each of length $3^{-k}$, thus we can regard it as the $3^{-k}$-cover of $F$. It gives as

\[\mathcal{H}^{s}_ {3^{-k}}(F) \leq \sum_ {i=1}^{2^{k}}\left\lvert 3^{-k} \right\rvert ^{s} = 2^{k} 3^{-ks}.\]At $s=\log_ {3}2$, in the $k\to \infty$ limit we have

\[\mathcal{H}^{s}(F) \leq 1.\]It is slighter harder to find an infimum of $\mathcal{H}^{s}$, so we will neglect it here. With even more effort one can show that $\mathcal{H}^{s}F=1$.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: