Note on Classical Kinks

Introduction

The reason why kinks (and domain walls) are of interest to us is that,

- they are known to exist in many laboratory systems and may exist in other exotic settings such as the early universe,

- they provide a relatively simple setting for studying the non-linear, non-perturbative physics,

- they shed light on the dynamics of phase transition.

Take the phi-4 model for example, the Lagrangian is (one of many different forms)

\[\mathcal{L} = \frac{1}{2}(\partial_ {\mu}\phi)^{2} - \frac{\lambda}{4} (\phi^{2} - \eta^{2})^{2}\]Then we can write down the kink solution, so-called $\mathcal{Z}_ {2}$ kink. The nice thing about $\mathcal{Z}_ {2}$ kink is that almost everything, from the kink solution to its energy, can be written down in closed form, as we shall see in the next chapter.

One can rescale the field $\phi$ and the coordinate $y$ such that the Lagrangian reads

\[\mathcal{L} = \eta^{2}\left[ \frac{1}{2} (\partial_ {\mu}\phi)^{2} - \frac{1}{4} (\phi^{2}-1)^{2}\right] .\]From this form it is clear that $\eta^{2}$ does not enter the classical equation of motion. It plays the rule of $\frac{1}{\hbar}$.

Derrick’s theorem states that, broadly speaking, in spatial dimensions greater than (or equal to) two, static, finite-energy, non-singular solutions to the equations of motion (like solitons) cannot exist for scalar field theories with purely local interactions. The theorem, formulated by G.H. Derrick in 1964, implies that such field configurations would be unstable and either collapse to a singularity or disperse. However, in higher spatial space we could still have topological structure with infinite energy, one example of such constructs is domain wall. Domain walls are extended planar structures separating two different vacua.

The Model

Phi-fourth kink

We will introduce the scalar field in (1+1) dimension. We regard the mass terms as a special type of self-interaction and put it in the interaction $U(\phi(x))$. The Lagrangian is

\[\mathcal{L} = \frac{1}{2} (\partial \phi)^{2} - U(\phi), \quad (\partial \phi)^{2} := \partial _ {\mu}\phi \partial ^{\mu}\phi.\]The Euler-Lagrange equation, or the equation of motion, is

\[\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \phi}= \partial_ {\mu} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial (\partial _ {\mu}\phi)}\]which in terms of $U(\phi)$ becomes

\[\partial _ {\mu}\partial ^{\mu}\phi + \frac{d U(\phi)}{d\phi} =0.\]For a static solution this simplifies to

\[\frac{d^{2}\phi}{dx^{2}} = \frac{dU(\phi)}{d\phi}.\]At a certain moment, the instantaneous energy is obtained by the Legendre transformation of the Lagrangian. Then the translational symmetry makes sure that the energy is a conserved quantity in time. Classically, given the field configuration, we just substitute it to the energy functional, then you have the total energy of the field configuration. After quantization, though, there will be infinite zero point energy. But for our concern we will just pretend it is not there and carry on to calculate the difference of energy. This is a common property to quantum field theory models, it is usually possible to calculate the difference of something rather than the things themselves, which will be divergent, as it often turn out to be.

The vacuum manifold is the manifold given by the minimum of $U( \phi )$. If there exists non-trivial maps

\[\text{boundary of space} \to \text{vacuum manifold}\]then we can construct soliton solutions. If there exists non-trivial maps from

\[\text{boundary of space-time} \to \text{vacuum manifold}\]then we can construct instanton solutions.

The energy functional can be further simplified if we introduce the so-called superpotential whose derivative gives the potential

Then the energy is given by

\[E[\phi] = \frac{1}{2} \int dx \, \left\{ \left( \partial _ {x}\phi \mp \frac{dW}{d\phi} \right) ^{2} \pm \boxed { 2(\partial _ {x}\phi)\left( \frac{dW}{d\phi} \right) }\right\},\]the boxed term can be easily shown to be a total derivative! The integral over

\[\left( \frac{\partial\phi}{\partial x} \right) \frac{dW}{d\phi}= \frac{\partial W}{\partial x}\]is a surface term, whose value only depends on the boundary condition of $\phi$. We have

\[E[\phi(x)] = \frac{1}{2} \int dx \, \left( \partial _ {x}\phi \mp \frac{dW}{d\phi} \right) ^{2} \pm W{\Large\mid}^{\phi(x=+\infty)}_ {\phi(x=-\infty)}\]which is of the form $E=(\cdots)^{2}+\mathrm{eq}$, the minimum of which is given by $\text{eq}=0$.

Recall that for the (anti-)kink solution, the boundary condition is taken such that the potential $U(x)$ takes different vacua at different space boundaries, then $W(x=\pm\infty)$ is fixed. The kink equation will just be

\[\boxed { \partial _ {x}\phi \mp \frac{dW}{d\phi} = 0, \quad U(\phi)=\frac{1}{2} \left( \frac{dW}{d\phi} \right)^{2}. }\]where the minus sign is chosen for kinks and plus for anti-kinks. This first-order PDF is called the BPS equation, named after Bogomolny, Prasad, and Sommerfield, the corresponding minimum of energy is called the BPS energy

\[E_ {\text{BPS}} = W{\Large\mid}^{\phi(x=+\infty)}_ {\phi(x=-\infty)}.\]Any field configuration with energy equal to BPS energy is said to saturate the BPS bound.

In terms of the potential $U (x)$, the BPS equation becomes

\[\partial _ {x}\phi = \frac{dW}{d\phi} = \sqrt{ 2U(\phi) },\]since the solution to it is a local minimum, the Euler-Lagrange equation is therefore automatically satisfied by solutions of the BPS equation, even though the latter is only a first order differential equation.

Kink solution

Next we turn to a specific potential, the well-known phi-fourth model. The self-interaction is defined to be

\[U(\phi) = \frac{1}{4} (\phi^{2}-1 )^{2} ,\]here we write the potential in a dimensionless and mathematically convenient form. The minimum of $U(\phi)$ is given by $\phi = \pm 1$. If you draw the potential, you’ll see that the potential has two symmetric minima and one maximal given by $\phi=0$.

The topological non-trivial solution that connects one vacuum to another smoothly is the classical kink solution. Solve the BPS equation we find

\[\phi_ {K} = \tanh \frac{x-a}{l_ {k}},\quad l_ {k} =\sqrt{ 2 }.\]The position of the kink is $a$ and $l_ {k}$ the characteristic size of it. To get a moving kink we just Lorentz boost it by velocity $v$,

Besides the kink solution, there is another static solution given by the elliptic sine function. But first, a digression to elliptic functions.

Jacobi elliptic functions

The circular functions arise from ratios of lengths in a circle. In a similar manner, the elliptic functions can be defined by means of ratios of lengths in an ellipse. Many of the key properties of the elliptic functions follow from simple geometric properties of the ellipse.

The most general form of Jacobi elliptic functions take two input, the first input behaviors as variable and the second as a parameter that controls the behavior of the function. The first input, the variable, is usually written as either $u$ or $\phi$, related by

\[u=\int_{0}^{\phi} d\theta \, \frac{1}{\sqrt{ 1-m \sin ^{2}\theta} }.\]The angle $\phi$ is called the amplitude, a rather confusing name to call an angle.

The most general form of elliptic integral is

\[f(x)= \int dx \, \frac{A+B}{C+D\sqrt{ S }},\quad A,B,C,D,S\in \mathbb{R}[x], \,\text{deg}(S)=3\text{ or }4.\]They can be considered as the generalization of the inverse of trigonometric functions.

Define something called modulus $k$ satisfy $0<k^{2}<1$. This is sometimes written in terms of $m:=k^{2}$ or the modulus angle $k=\sin \alpha$. The incomplete elliptic integral of the first kind reads

If we let $t=\sin \theta$ then

\[F(\phi,k)=\int_{0}^{\phi} d\theta \, \frac{1}{\sqrt{ 1-k^{2}\sin ^{2} \theta }}, \quad 0\leq \phi\leq \frac{\pi}{2}\]This is the incomplete Legendre elliptic integral. The complete Legendre elliptic integral is obtained by setting $\phi$ to its maximal value, i.e., $\phi=\pi / 2$ or $\sin \phi=1$.

The incomplete elliptic integral of the second kind reads

\[E(\phi,k)=\int_{0}^{\phi} d\theta \, \sqrt{ 1-k^{2}\sin ^{2} \theta }.\]or equivalently,

\[E(\phi,k)=\int_{0}^{\sin \phi} dt \, \sqrt{ \frac{1-k^{2}t^{2}}{1-t^{2}} } ,\quad 0\leq k^{2}\leq 1.\]Similarly, the complete elliptic integral of the first kink can be obtained by setting $\phi=\pi / 2$.

As an example of the Jacobian elliptic function $sn$ we can write

\[u(x=\sin \phi,k)=F(\phi,k)=\int_{0}^{x} dt \, \frac{1}{\sqrt{ (1-t^{2})(1-t^{2}k^{2}) }}\]then the inverse of $u(x)$ is defined to be

\[x = sn (u,k)\]or

\[u(x,k)=\int_{0}^{x} dt \, \frac{1}{\sqrt{ (1-t^{2})(1-t^{2}k^{2}) }} .\]While there are 12 different types of Jacobian elliptic functions based on the number of poles and the upper limit on the elliptic integral, the three most popular are the co-polar trio of sine amplitude, $sn(u, k)$, cosine amplitude, $cn(u, k)$ and the delta amplitude elliptic function, $dn(u, k)$ satisfy

\[sn^{2}+cn^{2}=1,\quad k^{2}sn^{2}+dn^{2}=1.\]Elliptic integral of the third kind reads

\[\Pi(\phi,n,k)=\int_{0}^{\sin \phi} dt \, \frac{1}{(1+nt)^{2}\sqrt{ (1-k^{2})(1-k^{2}t^{2}) }}\]with the same range of $k$. Or equivalently

\[\Pi(\phi,n,k)=\int_{0}^{ \phi} d\theta \, \frac{1}{(1+n\sin ^{2}\theta)\sqrt{ 1-k^{2}\sin ^{2}\theta }}.\]As mentioned before, the three standard forms of the Jacobi elliptic functions $sn,cn,dn$ are the sine, cosine and delta amplitude elliptic functions respectively. They are obtained by inverting the elliptic integral of the first kind

\[u\equiv u(\phi\mid k)\equiv u(\phi,k) \equiv F(\phi,k)=\int_{0}^{\phi} d \theta \, \frac{1}{\sqrt{ 1-k^{2}\sin ^{2} \theta }} .\]The parameter before $\sin ^{2}\theta$, i.e., $k$ is called the elliptic modulus, and the upper bound of the integral is called the Jacobi amplitude, denoted $\text{amp}$. The inverse of $u(\phi)$ is

and we can write the Jacobi elliptic functions in terms of $\phi$,

\[\begin{align*} sn(u,k)&=\sin \phi\equiv\sin(\text{amp}(u,k)), \\ cn(u,k)&=\cos\phi=\cos(\text{amp}(u,k)), \\ dn(u,k)&=\sqrt{ 1-k^{2}\sin ^{2}\phi }. \end{align*}\]These functions are doubly periodic generalizations of the trigonometric functions satisfying

\[\begin{align} sn(u,0)&=\sin u, \\ cn(u,0)&=\cos u, \\ dn(u,0)&=1. \end{align}\]since $u=\phi$ at $k=0$ .

The familiar kink solution in our notation is

\[\phi_ {K}(x) = \tanh\left( \frac{x-a}{l_ {K}} \right),\quad l_ {K}=\sqrt{ 2 }.\]where $a$ is the center of the kink and $l_ {K}$ the characteristic size.

It is easy using Mathematica to check that this solution satisfies both the second order equation of motion and the first order BPS equation. The anti-kink solution is just $-\phi_ {K}(x)$.

We claim without proof that there exists another static solution to the kink equation,

\[\phi(t)=\phi_ {0}\, \text{sn}(bx,k),\quad k^{2}=\frac{\phi_ {0}^{2}}{2-\phi_ {0}^{2}},\quad b^{2}=1-\frac{\phi_ {0}^{2}}{2}.\]What about a moving kink then? Firstly, the center of the kink will move with velocity $v$ thus we should replace $x-a$ with $x-a-vt$ where $v$ is the kink velocity. Secondly, from special relativistic we know that a moving frame will experience space contraction, thus we should multiply $x-a-vt$ by $\gamma$ factor, which is $\gamma=\frac{1}{\sqrt{ 1-v^{2} }}$ in natural units. Then a right-moving kink can be written as

\[\phi_ {K,v}= \tanh\left( \frac{x-a-vt}{\sqrt{ 2(1-v^{2}) }} \right).\]Kink-antikink collisions

When the kink and antikink are separated far away from each other, the interaction between them is negligible and the configuration with a kink and a antikink is simply the addition of kink and antikink solutions, up to some additive const to make sure that the field goes to the vacuum at the space boundaries. The center of the kink, for a right moving one, is $-a+vt$ where $v$ is the velocity. The kink-antikink configuration reads

\[\phi_ {K \overline{K}}(t,x)= \tanh\left( \frac{x-(-a+vt)}{\sqrt{ 2 }\sqrt{ 1-v^{2} }} \right) +\tanh\left( \frac{x-(a-vt)}{\sqrt{ 2 }\sqrt{ 1-v^{2} }} \right) -1,\]Note the last term $-1$ which is there to make sure the correct boundary condition is satisfied.

When the kink is too close to the antikink, the simple configuration Eq.(1) can no longer satisfy the equation of motion, in physical terms there will be non-linear interaction between the kink and the antikink. To find the solution to EOM we unfortunately have to rely on numerical calculation. To be specific, in numerical calculation we

- make space-time into 2-dimensional grid, the time grid is usually required to be finer than space grid to make the numerical results more reliable. Set up the initial condition, including the kink-antikink configuration and their initial speed.

- Time-evolve the initial spate using the equation of motion, make sure the position of the kink and antikink are not at the boundary of the space.

- Do some consistency checks, for example make sure that the total energy is (reasonably) conserved, or test that the numerical method we used, when applied to a kink at still, will remain a kink at still.

Even without specific calculation we can tell that the kink and antikink can’t just pass each other and keep moving, since if we move the antikink to the left and kink to the right, the field in the between will take value

\[\phi(x){\Large\mid}_ {x=0} = -1-1-1=-3\]where the first $-1$ comes from the antikink $\phi_ {\overline{K}}(\infty)=-1$, second from the kink and third form $-1$ in Eq.(1). However $-3$ is not a vacuum configuration! The energy will start to accumulate in between the kink and the antikink until the kinetic energy of them a re exhausted hence they have no other choice then to term back and follow the way they came. Thus they will “scatter” off each other.

A closer study of the case reveals that kink and antikink don’t always scatter off each other. During the scatter, the energy will dissipate, so the speed after scatter will decrease, if the initial velocity is too low, below some critical velocity $v_ {\text{cr}}$, there will not be enough energy left for the kink and antikink to escape each other, after collision they will try to separate but can only separate by a finite distance, before they could fully reform into kink and antikink, the energy would be depleted and they would have no choice to return to each other and scatter again, forming an oscillation. This object is often referred to as a bion or sometimes oscillon. In this note we will adopt the term bion, referring to the bound state of kink-antikink pair. In $3+1$ dimension, bions are also called quasi-breathers.

Note that bion is a quasi-long-lived state, which will eventually decay into trivial vacuum, but the time it takes is so long that we can safely treat it as a stable particle.

For $v_ {\text{in}}>v_ {\text{cr}}$, where $v_ {\text{in}}$ is the incoming velocity, kink and antikink always bounce and escape to infinity. Below $v_ {\text{cr}}$ things are more interesting, there exists windows where the kink-antikink pair will scatter once, deposit some energy between them, the deposited energy form a vibrational mode, the kink-antikink pair come back to each other after a little while and bounce again, this time retrieves the deposit energy, and move away from each other to the infinity. The time of bounce needed before they eventually escape each other could be two, three, etc., the corresponding incoming velocity windows are called two-bounce escape windows, three-bounce escape windows, and so on.

Collective Coordinate Approximation

Consider again the kink-antikink scatter. Work in the center of mass frame, the position and velocities are symmetric, we need only one parameter, namely the position of the kink as a function of time $t$, to uniquely fix the configuration. Use $a(t)$ to denote the position of the kink. Now the question is, can be write down a (low energy) effective theory in terms of $a(t)$ only? If we can, it would be the collective coordinate approximation (CCA) model.

We can substitute the field configuration

\[\phi_ {K \overline{K}}=\tanh\left( \frac{x+a(t)}{\sqrt{ 2 }} \right) - \tanh\left( \frac{x-a(t)}{\sqrt{ 2 }} \right) - 1\]into the phi-fourth Lagrangian for $\phi(x,t)$ and obtain an effective Lagrangian in terms of $a(t)$ then integrate over the space. It should adopt the form

\[L_ {\text{CCA}} = L_ {\text{CCA}}(a,\dot{a}) = \frac{1}{2} m_ {a}\dot{a}^{2}-V(a)\]where $m_ {a}$ is the effective mass for the kink, it is position-dependent in general.

At large separation, we find that the mass parameter $m(a)$ and the effective potential $V(a)$ both approach $2M_ {K}$, the mass of two isolated static kinks. To be specific, we have

\[m(a)=I_ {+}(a),\quad V(a) = \frac{1}{2} I_ {-}(a) +\frac{1}{4} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} dx \, (1-\phi^{2}_ {K \overline{K}})^{2}\]where

\[I_ {\pm }= 2M_ {K} \pm \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} dx \, \frac{1}{\cosh ^{2}((x+a) / \sqrt{ 2 })\cosh ^{2}((x-a) / \sqrt{ 2 })} ,\]where the integral goes to zero exponentially as $a$ increases.

The effective potential can more or less account for the free bounce and formation of a bion, but can not explain the escape window, or the relativistic effects that might happen when the speed of kinks are high.

Gluing static solutions

Another way to construct the bion configuration is by gluing together three piece, 1) the left half of the kink solution, 2) half a elliptic sine function and 3) the right half of the antikink. Then the numerical methods can be used to evolve the state. However, to start the numerical evolvement, we also need to know the field configuration at the next-to-start time-slice, we can fix it by hand, by shrink the elliptic sine function a little bit, let $\phi_ {0}$ decrease a little bit.

Kink-impurity interactions

Roughly speaking we have two ways to study the evolution of kinks-antikink states,

- Take the superposition of two static solutions, i.e. the kink solution and the antikink solution. It is not strictly speaking the solution of the equation of motion, thus the equation of motion will evolve it in a non-trivial way.

- Instead, we can start with some exact solution of the equation of motion, but then use a slightly different equation of motion to evolve it. This is the situation encountered in the description of kink interacting with impurities.

The impurities could appear for a couple of reasons. For example, the phi fourth theory is usually the low energy effective theory of some other theory defined at UV, and this “UV completion” of our phi fourth theory might have some impurities, or defects, which can then get passed on to the phi-fourth theory. This impurity could be some defect embedded in the crystal structure, for example. To describe such process, we can modify the phi-fourth potential by

\[\frac{1}{4}(\phi^{2}-1)^{2}\to \frac{1}{4} (\phi^{2}-1)^{2}(1-\epsilon \delta(x-x_ {0})).\]When $\epsilon>0$ the defect acts like a potential barrier, if $\epsilon<0$ a well.

With this modified potential we can then talk about its equation of motion. In numerical calculation we can approximate the delta function either by a Kronecker delta function, or a Gaussian shape high and narrow.

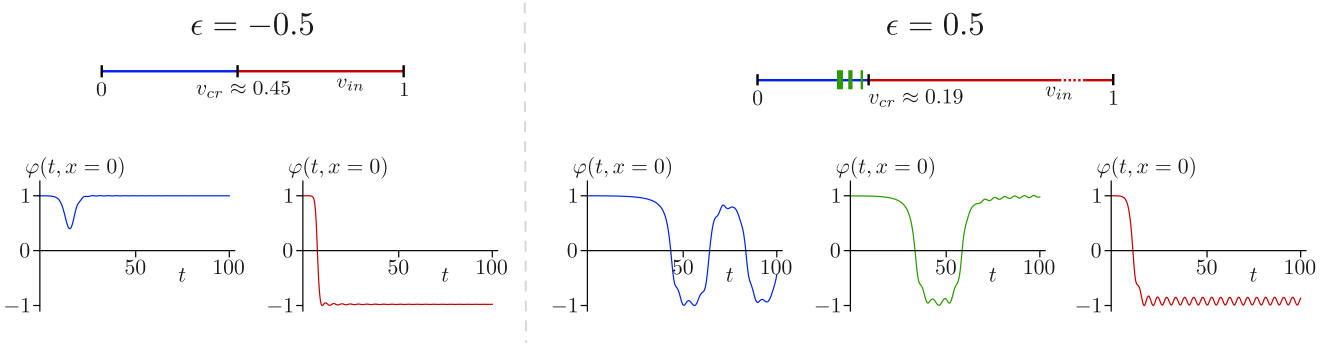

To be more specific, consider a static kink solution starting from $a=6$, moving towards am impurity located at $x_ {0}=0$, with fixed impurity strength $\left\lvert \epsilon \right\rvert=0.5$. The figure below shows the phase diagram.

On the left panel a repulsive impurity $\epsilon=-0.5$ is shown, for low velocity the kink will bounce back, as shown by the blue line; for high velocity the kink can overcome the impurity barrier and keep propagating, as shown by the red line.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: