Note on the kink mass correction in 3D Part I

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

We will establish the model and notation in this section. First, some nomenclatures.

Shape modes: In theories with a kink solution, the equation of motion in the background of the kink typically has discrete, bounded solutions. They are called shape modes. They are localized around the kink. Shape modes represent small fluctuations or deformations of the kink’s shape. Unlike the continuum of delocalized modes that represent free particle states, the shape modes are confined to the vicinity of the kink, with discrete energy levels.

Oscillons: They are localized, non-solitonic, and semi-stable field configurations that oscillate in time. They are interesting because they represent a form of partial stable, localized energy concentration that can persist for long times, even though they are not topologically protected like solitons or kinks. Oscillons are found in various nonlinear field theories and have been studied in different contexts, including cosmology and condensed matter physics. Their persistence and behaviors under various conditions are subjects of ongoing research in theoretical physics. However, it is believed that quantum correction will make oscillons rapidly decay into a pair of fundamental particles.

The Unruh effect: The Unruh effect is a prediction in quantum field theory, stating that an observer accelerating through a vacuum will perceive a thermal bath of particles, whereas an inertial observer would see none. This effect arises from the realization that the concept of a vacuum state (or empty space) is observer-dependent. For an accelerating observer, what appears as empty space to an inertial observer is seen as a warm gas of particles. This effect, named after physicist William Unruh, highlights the interplay between quantum theory and relativity, especially in contexts like black hole physics.

In the frame work of the linearized soliton perturbation theory, we can systematically study the quantum corrections to both static and time-dependent solitonic solutions.

Firstly, we work in the Schrodinger picture where the operator are time-independent while the wave functions (vectors in Hilbert space) are time dependent. Secondly, we will start with the Hamiltonian formalism where the canonical momentum, $\pi$, is considered as a fundamental ingredient, rather than the time derivative of $\phi$, the field of the Lagrangian.

In $2+1$ dimension, the Hamiltonian $H$ is the integral of the Hamiltonian density $\mathcal{H}$ over the 2D manifold of space alone,

\[H = \int_ {M} d^{2}x\, \mathcal{H}(\phi,\pi),\quad \mathcal{H}=\frac{1}{2}\pi^{2}(x)+\frac{1}{2} (\partial_ i \phi)^{2} + \frac{1}{\lambda}V(\sqrt{ \lambda }\phi(x))\]Dimensional analysis

In Lagrangian formalism, $[S]=[\hbar]$ where $S$ is the action, and $S = \int d^d x \, \mathcal{L}$, where $\mathcal{L}$ is the Lagrangian (density) and $d$ is the space-time dimension. Note that right now we are working with a partially “natural” units, where $c=1$ but $\hbar \neq 1$. Since $c=1$ we still have $[x] = [t]$, namely $L=T$ ($L$ is length and $T$ is time), but no longer do we have $T=E^{-1}$ since this is a result of $[\hbar]=ET=1$ (recall that $\hbar \omega=E$, meaning $[\hbar \omega]=E$, and $\omega$ is the frequency with dimension $1 / T$ ).

Let $d$ be the dimension of spacetime, in the partial natural unit we have

\[\int d^{d}x \, \mathcal{L}\sim \hbar \implies [\mathcal{L}]=[\hbar] L^{-d}\]Take a specific term, say $(\partial \phi)^{2}$, to continue the analysis,

\[[(\partial \phi)^{2}] = L^{-2} [\phi^{2}] = [\mathcal{L}] = [\hbar]L^{-d} \implies [\phi^{2}]=[\hbar] L^{2-d}\]which is

\[[\phi] = [\sqrt{ \hbar }] \, L^{1-d / 2}.\]This agrees with the convention that field operator $\phi$ scales as $\sqrt{ \hbar }$. Furthermore, this scaling property does not depend on the spacetime dimension $d$, it holds for any spacetime dimension.

I don’t think the $\hbar$-dependence given by Eq. (1) is unique, apparently there exist other possibilities, we can move $\hbar$ around in the Lagrangian, just to make sure that the action altogether is of dimension $\hbar$. However it seems that $\phi\sim \hbar^{1/2}$ is indeed the most convenient option. Another way to see the advantage of this choice is from the action,

\[S \sim \hbar \sim \int d^{4}x \, (m^{2} \phi^{2}+(\partial \phi)^{2} +U(\phi)),\]then

\[\int d^{4}x \, \left[ m^{2} \xi^{2}+(\partial \xi)^{2} + U(\xi) \right] \sim 1, \quad \xi:= \frac{\phi}{\sqrt{ \hbar } } .\]In this way, we can absorb $\hbar$ into the definition of $\phi$, this is similar to absorbing the coupling $g$ into the field definition in gauge theory. We now define $\xi$ to be independent of $\hbar$.

Having fixed the $\hbar$-dependence of $\phi$, we can substitute it to the potential $U$, for example the $\phi^{4}$ model to determine the $\hbar$ dependence of the coupling,

\[[S]\sim\int d^{d}x \, \lambda \phi^{4} \sim L^{d} [\lambda][\hbar^{2}] L^{4-2d} = L^{4-d}[\hbar^{2}][\lambda],\]on the other hand we already know that $S\sim \hbar$ so

\[L^{4-d}[\hbar^{2}][\lambda] = [\hbar] \implies [\lambda \hbar] = L^{d-4}.\]If we choose $L$ to be the fundamental unit instead of energy $E$, it is clear the $\lambda \hbar$ is independent of $\hbar$. Plus, we see that $d=4$ is special.

For the sake of completeness, let’s consider the mass term in the Lagrangian. Similar to what we have for the kinetic term,

\[[m^{2} \phi^{2}] = E^{2}\, [\phi^{2}] = [\mathcal{L}] = [\hbar]\,L^{-d} \implies [\phi] = [\sqrt{ \hbar }]L^{-d/2}E^{-1} .\]Dimension and measurement

If two things are of the same dimension, for example, say

\[[A] \sim [a] = L\]where $\sim$ means having the same dimension. Then we can use one of them as the unit to measure the other, say, use $a$ as the “ruler” to measure $A$, the result $\widetilde{A} :=A / a$ is a dimensionless number.

Suppose $[\phi]=[\hbar]^{1/2}$, another way to say the same ting is $\phi \sim \sqrt{ \hbar }$, note that the tilde does not imply any relation between the values of $\phi$ and $\sqrt{ \hbar }$, it only means that they have the same dimension. The point is, since they have the same dimension, we can use one of them to measure the other, for example we can define

\[\tilde{\phi} = \phi / \sqrt{ \hbar }\]which is a dimensionless number. Since $\hbar$ scales the “quantumness”, the more classical the world is, the smaller $\hbar$ (and $\sqrt{ \hbar }$), hence the bigger numeric value of $\tilde{\phi}$.

In the partial natural units, I’d like to think there are two fundamental “rulers” to measure all the quantities, such as mass, coupling, field, etc. One of them is the unit of energy, for example $\text{MeV}$, the other is $\hbar$ whose dimension is $ET$. To measure the length of something, we can use $\frac{\hbar}{\text{MeV} }$ as unit. The advantage of the partial natural unit is that it makes explicit the $\hbar$ factor, revealing the direct relations between quantities with $\hbar$, which is the scale of quantumness, this enables us to discern the importance of various quantities in the classical limit, making the analysis regarding semi-classical more straightforward.

1.2 Digression on $\hbar$-expansion

To appreciate the importance of $\hbar$, just recall that in canonical quantization $[x,p]=i\hbar$, $\hbar$ enters explicitly in the commutation relation, providing the fundamental basis of quantum theory. This is also true in the case of quantum field theory. Furthermore, at each order of an expansion in $\hbar$, the physical symmetries (Lorentz invariance, $U(1)$ symmetry, etc.) must be satisfied, otherwise there will be some special value of $\hbar$ only at which the symmetries are preserved, which is just strange.

In the unit where $c=1$, the Planck’s constant $\hbar$ has the unit of action, or rather the action has the unit of $[\hbar]=ET$, where $E$ is the energy scale and $T$ the time. The textbook proof of the equivalence between loop expansion and semi-classical expansion, i.e. $\hbar$-expansion usually goes as follows. First write the partition function (with the source term) with $\hbar$:

\[Z[J(x)] = \int \mathcal{D}\phi \, \exp \left\lbrace \frac{i}{\hbar} \int d^{d}x \, (\mathcal{L}+\hbar J \phi) \right\rbrace ,\]where $J=J(x)$ is the source term. Note that the source term has an $\hbar$ multiplied with it. Splitting the Lagrangian into free and interacting part (depends on the choice), we can extract out the interaction and put it in the front of the free partition function:

\[Z[J] = \exp \left\lbrace \frac{i}{\hbar}\mathcal{L}_ {\text{int}}\left( \frac{1}{i} \frac{\delta}{\delta J} \right) \right\rbrace Z_ {0}[J],\]where $\mathcal{L}_ {\text{int}}$ is the interacting Lagrangian and

\[Z_ {0}[J] = \int \mathcal{D}\phi \, \exp \left\lbrace \frac{i}{\hbar}\int d^{d}x\, (\mathcal{L}_ {0}+ \hbar J\phi) \right\rbrace\]is the free partition function with the source. It can be integrated out in the closed form (for the level of rigorous for a physicist) to give

\[Z_ {0}[J] = N \exp \left\lbrace - \frac{i}{2}\hbar \int d^{d}x d^{d}y \, J(x) \Delta_ {F}(x-y)J(y) \right\rbrace,\]where $\Delta_ {F}$ is the Feynman propagator. It shows that each propagator contributes a factor of $\hbar$.

Now, since each diagrammatic vertex is a result of a functional derivative $\frac{i}{\hbar }\mathcal{L}_ {\text{int}}\left( \frac{\delta}{\delta J} \right)$, each vertex contributes a factor of $\frac{1}{\hbar}$. Then, using some relations between the numbers of loops, propagators and vertices (it depends on the specific model), and amputate the external legs, it can usually be shown that: a general graph with $L$ loops is proportional to $\hbar^{L-1}$. Thus an expansion in the number of loops is also an expansion in powers of $\hbar$.

It turns out that there are more than one way to assign $\hbar$-dependence for quantities such as the mass $m$, the coupling $g,\lambda$ etc. A criterion for the “right” choice is that, at $\hbar\to 0$ limit, the quantum theory agrees with the classical theory. As an example, Stanley Brodsky and Paul Hoyer in their paper used the quantum mechanical harmonic oscillator as an example in Eq.(1). The gist is that, you can rescale $x$ to $x / \sqrt{ \hbar }$, then the propagator is formally independent of $\hbar$. However, this will change how we view distance, in the $\hbar\to 0$ limit, for a fixed distance $L$, the “length” measure will increase as $1 / \sqrt{ \hbar }$, hence we are going to smaller and smaller area.

It is generally understood that each loop contribution to amplitudes is associated with one factor of $\hbar$. However, to fully define the $\hbar\to 0$ limit one need to specify the $\hbar$ dependence of various quantities in the Lagrangian as mentioned before, such as the field operator, the mass, the coupling, etc. This is not as straightforward as one might think, for $\hbar$ not only appears in the action $iS / \hbar$ but also appears in the Lagrangian. In Brodsky’s paper mentioned above, the authors proposed a way to establish the $\hbar$ dependence such that the loop and $\hbar$ expansions are equivalent. We will go to more details in the following.

First, regard $\hbar$ as a constant of nature with certain dimension, use $\hbar$ to make terms in the Lagrangian dimensionless.

Again let’s work with the assumption that $c = \epsilon_ {0} = 1$. Require $[S]=\hbar$, and $\alpha_ {s} = g^{2} / 4\pi \hbar$ is dimensionless, the latter implies that $[g]=\sqrt{ \hbar }=\sqrt{ ET }=\sqrt{ EL }$. From the self-energy of gluons $G_ {\mu \nu}G^{\mu \nu}$ where $G = \partial A - \partial A +ig / \hbar [A,A]$ we have

\[[A] = \sqrt{ \frac{E}{L} }.\]Similarly, in scalar QED model the classical electric charge $e$ and mass $m$ are divided by $\hbar$,

\[S_ {\text{sQED} } = \int d^{4}x \, \left\lbrace \left\lvert D\phi \right\rvert ^{2}-\frac{m^{2} }{\hbar^{2} }\left\lvert \phi \right\rvert ^{2} \right\rbrace , \quad D = \partial +i \frac{e}{\hbar }A.\]The boson field dimension

\[[\phi]=[A]= \sqrt{ \frac{E}{L} }.\]Fermion fields are more complicated, since they have no classical counterparts, their dimensions are convention-dependent. We will deal with fermions in a different note perhaps.

Second step is to specify $\hbar$ dependence of all quantities appearing in the action.

The choice made by Brodsky and Hoyer is as following:

\[\widetilde{A}:= \frac{A}{\sqrt{ \hbar } },\quad \tilde{\phi}:= \frac{\phi}{\sqrt{ \hbar } }\]where $\widetilde{A},\tilde{\phi}$ are $\hbar$-independent. Similarly, define the following $\hbar$-independent quantities

\[\widetilde{g}:= \frac{g}{\hbar},\quad \widetilde{e}:= \frac{e}{\hbar},\quad \widetilde{m}:= \frac{m}{\hbar}.\]Then one can write the Lagrangian in terms of these $\hbar$-independent quantities to check the $\hbar$ dependence explicitly. It turns out that, at least in the simple models discussion in the paper, $\hbar$ always appears in the combination

\[\widetilde{g}\sqrt{ \hbar } \quad \text{and}\quad \widetilde{e}\sqrt{ \hbar }\]that is, with the coupling. Hence loop correction of $\mathcal{O}(g^{2},e^{2})$ will be of order $\hbar$.

This derivation is equivalent to the standard one of, for example, Mark Srednicki’s textbook, which associates a factor $\hbar$ to each propagator and $h^{-1}$ with each vertex, and assume the parameters appearing in the action to be independent of $\hbar$.

Fore more details please refer to Brodsky and Hoyer’s paper mentioned above.

2 Kinks in d-Dimension

In R. Jackiw’s 1976 paper, he made three assumption:

- The energy (mass) is finite;

- The energy is locally minimum, meaning the soliton is stable;

- The potential $U$ depends on a coupling constant $\lambda$ according to the scaling law

The choice is such that all the $\lambda$ dependence are now moved to the pre-factor $1 / \lambda$. As for $\hbar$-expansion, we take the scheme such that $\hbar$-expansion agrees with $\lambda$-expansion, namely each loop brings in a factor of $\hbar$.

Let the Hamiltonian be

\[H = \int d^{2}x \, : \mathcal{H} :_ {a},\quad \mathcal{H}(x) = \frac{\pi^{2} }{2} + \frac{(\partial_ {x}\phi(x))^{2} }{2} + \frac{1}{\lambda} V\left(\sqrt{ \lambda}\, \phi(x) \right).\]Now, in order to get the equation of motion, we have two options: 1) Legendre-transform the equation to the Lagrangian formalism and adopt Euler-Lagrange equation, or 2) stick with the Hamiltonian formalism and adopt the Hamiltonian equations of motion (Hamilton equations) instead. Here we will take the second option.

Recall that the Hamilton equations in classical field theory reads

\[\begin{align*} \frac{\delta \mathcal{H} }{\delta \phi_i} &=-\dot{\pi}(x), \\ \frac{\delta \mathcal{H} }{\delta \pi_i} &= \dot{\phi}_i. \end{align*}\]This is a non-trivial generalization of the familiar Hamiltonian in classical mechanics, non-trivial since the connection between variational derivative and partial derivative is not as simple as one might think, we have

\[\frac{\delta \mathcal{H} }{\delta \phi} = \frac{\partial\mathcal{H} }{\partial \phi } - \left( \partial_ x\frac{\partial \mathcal{H} }{\partial(\partial_ {x}\phi)} \right).\]Taking everything into consideration, we obtain the equation of motion by straightforward calculation. But before going there, let’s rewrite the Hamiltonian in a more compact form:

\[\boxed{ \lambda \, \mathcal{H} = \frac{1}{2} \tilde{\pi}^{2} + \frac{1}{2} \vec{\nabla}^{2}\,\tilde{\pi} + V(\tilde{\phi}),\quad \tilde{\pi} := \sqrt{ \lambda }\, \pi,\quad \tilde{\phi} := \sqrt{ \lambda }\,\phi. }\]Then we can first obtain the EOM in terms of $\tilde{\phi}$ and $\tilde{\pi}$, the changing to un-tilded version is trivial. Finally we have

\[\ddot{\phi} - \vec{\nabla}^{2} \phi(x,t) + \frac{1}{\sqrt{ \lambda } } V^{(1)}(\sqrt{ \lambda }\phi) = 0\]with definition

\(V^{(n)} := \frac{ \partial^{n } V(\tilde{\phi})}{ \partial \tilde{\phi}^{n} }.\)

2.1 Normal modes and quantization

When kink solutions are placed in more than one spatial dimension, they become extended planar structures called “domain walls.”

Now, how can we borrow the kink result form 2D directly to 3D? Consider a static kink solution in the $x$ direction

\[\phi(x,y) =: f(x,y)=: f_ {1}(x)\times f_ {2}(y) ,\]where we have assumed the possibility of separation of variables. To say the kink is in the $x$ direction is to say the solution satisfies the equation of motion in the $x$ direction,

\[\frac{ \partial^{2} f(x,y) }{ \partial x^{2} } = \frac{1}{\lambda} \frac{ \partial V }{ \partial \phi } = \frac{1}{\sqrt{ \lambda } } \frac{ \partial V }{ \partial \tilde{\phi} } = \frac{1}{\sqrt{ \lambda } }V^{(1)}(\tilde{\phi}).\]First, consider the case of 2D spacetime. Writing the filed as a kink background plus fluctuation,

\[\phi(x,t) =: f(x) + {\mathfrak g}(x) e^{ -i\omega t }\]where $f(x)$ is the 1-dimensional kink solution, the equation of motion in terms of ${\mathfrak g}$ reads

\[[-\omega^{2}-\partial_ {x}^{2}+V^{(2)}(\sqrt{ \lambda }f(x))]\, {\mathfrak g}(x) = 0.\]As we mentioned before, there are three kinks of solutions: the zero mode, the shape mode and the continuum.

The equation of motion is the Sturm-Liouville equation. A general Sturm-Liouville problem is typically written in the form:

\[\frac{d}{dx}\left[ p(x) \frac{dy}{dx} \right] - q(x)y + \lambda r(x)y = 0\]Here, $y$ is the function of the variable $x$ that we are solving for, and $p(x)$, $q(x)$, $r(x)$ are known functions that specify the particular Sturm-Liouville problem. The parameter $\lambda$ is often referred to as the eigenvalue.

Key characteristics and applications of the Sturm-Liouville equation include:

-

Eigenvalue Problem: The Sturm-Liouville equation is an eigenvalue problem. The solutions $y(x)$ are eigenfunctions, and the associated values of $\lambda$ are eigenvalues. These eigenvalues are typically discrete and can be ordered as a sequence $\lambda_1, \lambda_2, \lambda_3, \ldots$, where each $\lambda_n$ corresponds to a particular eigenfunction $y_n(x)$.

-

Orthogonality and Completeness: The eigenfunctions of a Sturm-Liouville problem are orthogonal with respect to the weight function $r(x)$. This property is crucial in solving partial differential equations, as it allows the expansion of functions in terms of these eigenfunctions (similar to Fourier series).

-

Boundary Conditions: Sturm-Liouville problems are typically accompanied by boundary conditions that the solutions must satisfy. These conditions are usually specified at the endpoints of the interval in which the equation is defined.

-

Physical Applications: The Sturm-Liouville problem appears in various areas of physics, such as quantum mechanics (in solving the Schrödinger equation), heat conduction, wave propagation, and vibrations analysis. It is essential in the separation of variables technique for solving partial differential equations.

-

Self-Adjoint Form: The equation is often referred to as a self-adjoint form, which has important implications in the theory of linear operators and functional analysis.

In our case, the weight function is trivial.

We will denote the zero mode by ${\mathfrak g}_ {B}$ and the shape mode by ${\mathfrak g}_ {S}$. The $B$ in ${\mathfrak g}_ {B}$ has a historical reason, but in our note it is just part of the name. The normalization conditions are

\[\int dx \, {\mathfrak g}_ {S}^{2} = \int dx \, {\mathfrak g}_ {B}^{2} = 1 , \quad \int dx \, {\mathfrak g}_ {B}{\mathfrak g}_ {S} = 0 ,\quad \int dx \, {\mathfrak g}_ {k}(x){\mathfrak g}_ {p}(x) = 2\pi i\delta(p-k).\]The sign of ${\mathfrak g}_ {B}$ is fixed using

\[{\mathfrak g}_ {B}(x) = - \frac{f'(x)}{\sqrt{ Q_ {0} } },\]where $f$ is again the kink solution.

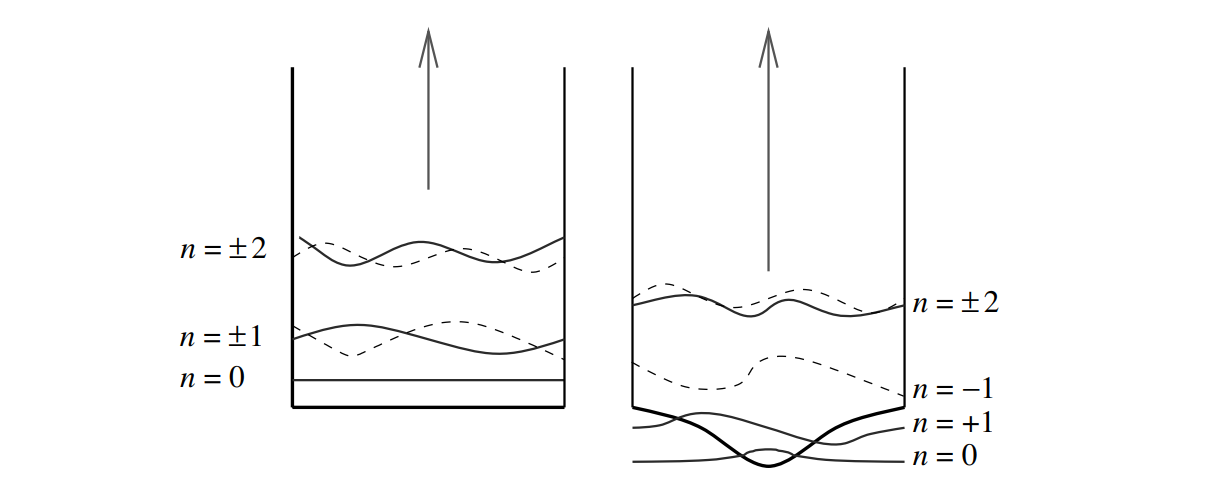

We choose to expand in the $x$ direction in normal modes (in the kink background), while expanding in the $y$ direction in plane waves. The 2D momentum is $\vec{k}=\left\lbrace k_ {x},k_ {y} \right\rbrace$, where $k_ {x}=\left\lbrace B,S,k \right\rbrace$, $B$ for the zero mode (bounded solution), $S$ for the shape mode (also bounded) and $k$ for the continuum. A nice illustration of normal modes in the background of kink is shown in the figure below, which I shamelessly copied from Tanmay Vachaspati’s book, all the credits goes to Vachaspati.

We want to expand the static fluctuation field $\phi(r)$ in terms of normal modes. Since we have defined the indices $k$ in ${\mathfrak g}_ {k}(x)$ to include everything, we can conveniently write the field expansion as

\[\begin{align*} \phi(r) &= \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \frac{ d^{d}k}{(2\pi )^{d} } \, \left( B_ {k} ^{\ddagger} +\frac{B_ {-k} }{2\omega _ {k} } \right){\mathfrak g}_ {k} (r),\\ \pi(r) &= \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \frac{ d^{d}k}{(2\pi )^{d} } \, \left( B_ {k} ^{\ddagger} -\frac{B_ {-k} }{2} \right){\mathfrak g}_ {k} (r), \end{align*}\]where $r = (x,y)$. We adopt the convention

\[B^{\ddagger}_ {k} = \frac{B^{\dagger}_ {k} }{2\omega _ {k} }.\]This helps us to switch between different conventions for the field expansion.

We have omitted the vector sign (or bold font) in $r$ since it would not cause any misunderstanding. We assume (quite reasonably) the separation of variables $x$ and $y$ for 2D normal modes ${\mathfrak g}(r)$,

\[{\mathfrak g}(r) = {\mathfrak g}_ {x}\times g_ {y},\quad {\mathfrak g}_ {x} = \text{kink normal modes},\, {\mathfrak g}_ {y} = \text{plane waves.}\]The quantization in terms of $\phi$ and $\pi$ reads

\[[\phi(r),\pi(r')] = i\delta^{(d)}(r-r').\]This represents the fundamental quantization relation, unaffected by the selection of sectors. We haven’t given a formal definition of sectors, roughly speaking, within each sector, there exists a distinct set of normal modes for expanding both $\phi$ and $\pi$. Each mode must conform to the aforementioned relation, namely the quantization relation given in space-time positions $r$. Ultimately, the difference across different sectors lies in the diverse backgrounds (regarded as classical functions) used for field expansion. However, as we are analyzing the same theory within the same space-time, the theory should be quantized only once, and, all sectors must consistently align with the same quantization process.

2.2 Renormalization methods review

Things does get more complicated when renormalization is included. The commonly used renormalization method include (but not limited to):

-

Dimensional regularization. This is particularly useful in 4D. This technique regularizes integrals by analytically continuing the number of dimensions of space $d$, usually reduce it by an infinitesimal quantity $\epsilon$. It preserves the gauge symmetry and Lorentz invariance. -

Cutoff regularization. This method introduces a high-energy cutoff in the energy. By doing this we are making the momentum integrals finite by force, but as a price we would introduce a new parameter $\Lambda$ with the dimension of energy. This $\Lambda$ has profound physical consequence, such as in dimensional transmutation and, most importantly, the Wilsonian RG flow. -

Pauli-Villars Regularization.This approach involves adding hypothetical heavy particles to the theory to cancel out the divergences. The mass of the heavy particles acts effectively as the cutoff in the integrals. -

Lattice reguglarization. This method discretizes the spacetime into a lattice. Computations are performed on this lattice, the spacing between different sites, or the resolution of the lattice serves as a cutoff.

There also exist tons of other renormalization methods, such as holographic renormalization, Hopf algebra renormalization, Connes-Kreimer renormalization, and so on. They sounds like fun but, unfortunately, they lie beyond the scope of our work and my comprehension.

Different renormalization methods may yield different results depending on the specific sector they are applied to. For instance, the momentum cutoff method produces distinct outcomes when used in the trivial vacuum sector compared to the one-kink sector. From my perspective, it seems more appropriate to consider the regularization method as an integral part of the quantization process. Quantization itself is not a natural, free functor (just means a ); whether one opts for geometrical quantization or path integral quantization (among other methods), additional elements are always needed. For example, incorporating a momentum cutoff is often a crucial step.

Different sectors also seem to give different perspectives regarding the relations between different regularization methods. For example, in trivial vacuum sector (which we will just call vacuum sector), the momentum cutoff method is closely connected to the lattice renormalization method, by roughly $\Lambda = 2\pi / a$ where $a$ is the lattice spacing. This very relation is harder to see in, for instance, one-kink sector (which we will just call kink sector).

A natural question that follows is, if there exists a regularization method that applies to all the sectors (unlike the momentum cutoff renormalization) equally well? If so, which one? Apparently the space-time itself is the common ground of all sectors, since the lattice regularization is dependent on spacetime alone, it is independent of the specific mode-expansion we adopt for fields, so it seems reasonable to use it as the renormalization scheme. Other advantages of lattice renormalization includes, 1) it made obvious the Wilsonian RG flow, which is continuous change of various parameters in the theory depending on a continuous change of the lattice size. 2) The connection between the lattice quantization and momentum-cutoff renormalization is already know in the trivial vacuum sector. We just need to find a way to generalize it to other sectors.

2.3 Lattice quantization

In our work we will start with the lattice quantization. Recall that the canonical quantization relation in a continuous $d$-dimensional spacetime reads

\[[\phi(r),\pi(r')] = i \delta^{(d)} (r-r'),\]In lattice quantization, the continuous spacetime of the theory is replaced by a discrete set of points, and the fields are defined only at these points. It is a powerful, comprehensive change of viewpoint, not only of numerical importance, but really alters our view of spacetime. In principal we can translate all concepts we have defined in spacetime continuum into the lattice spacetime, such as the gauge connection, gauge field strength, etc. Sometimes, it is convenient to think the lattices as “sample points” of a spacetime continuum. In this view, between the lattice sites there maybe exists something other than the pure void, but it is meaning less to talk about them anyway. This view is rather useful when discussing the connection between lattice quantization and momentum cutoff quantization.

The commutation relation on a lattice should take the form

\[[\phi_ {i},\pi_ {j}] =i\delta_ {ij},\]where $i,j$ are the indices of different sites.

Recall that in canonical quantization, Eq. (2.1) translate to the momentum space rather trivially, yielding

\[[a_ {p},a^{\dagger}_ {p'}] = (2\pi)^{d} \delta^{(d)}(p-p').\]So the question is, how does the lattice commutation relation translates to different sectors? Particularly, in the trivial vacuum sector and the one-kink sector?

2.3.1 Latticization of scalar field

Write the scalar field $\phi$ in continuum as as function of spacetime position $\phi(x)$, and write the lattice position as a label of the field $\phi_ {a^{\mu} }$, where $a^{\mu}=m^{\mu} a$, $m^{\mu}\in \mathbb{N}^{d}$ is the $d$-dimensional count of the lattice site, $a$ is the lattice distance. The summation on lattices goes to integral in the continuous limit with the following dictionary,

\[\begin{align*} \sum_ {m^{d} } &\to \int, \\ a^{d} &\to d^{d}x,\\ f_ {a^{\mu} } &\to f(x) \end{align*}\]where $m^{d}$ indicates the $d$-dimensional lattice. Combined together we have the familiar formula

\[\sum_ {m^{d} } a^{d} f_ {a^{\mu} } \to \int d^{d}x \, f(x).\]We can define two types of differences, corresponding to derivatives in the continuous case

\[\begin{align*} \partial_ {\mu} f_ {x} &= \frac{1}{a} (f_ {x+\hat{a}^{\mu} }-f_ {x}),\\ \partial'_ {\mu} f_ {x} &= \frac{1}{a} (f_ {x}-f_ {x-\hat{a}^{\mu} }), \end{align*}\]where $\hat{a}^{\mu}$ is a vector in direction $x^{\mu}$ of length $a$, namely $\hat{a}$ moves to the next lattice site in the $x^{\mu}$ direction. These two differences are like differences “from right” and “from left”. For smooth functions of course their continuous limit all give the derivative.

The interesting thing is that these two types of differences are kind of dual to each other. Define an inner product

\[(f_ {x},g_ {x}) := \sum_ {x} f_ {x} g_ {x},\]similar to the case of differential forms, then

\[(f_ {x},\partial g_ {x}) = (-\partial' f_ {x},g_ {x}),\]which corresponds to the integral by part

\[\int \, f\partial g = \int \,(-\partial f) g.\]2.3.2 Second quantization in the vacuum sector

First let’s review how the second quantization is achieved in the vacuum sector without latticization, namely on a continuum of spacetime of dimension $d+1$. This is what we learnt from textbooks.

Note that we will adopt a slight change of variable here. Before we used $\vec{r}$ to denote the spatial vector where $\vec{r}=(x,y, \cdots)$ since in two dimensional space time, it is easier to write $x,y$ than $x_ {1},x_ {2}$. However, since now we are dealing with $d+1$ dimensional spacetime, we will also adopt a different convention, namely $x=(t,\vec{x})$ where $\vec{x}$ is a $d$-dimensional vector with components $x_ {1},\cdots,x_ {d}$. In summary, Latin letters without a vector sign $x$ are covariant $d+1$-vectors, the generalization of $4$-vector to arbitrary dimension.

The simplest special relativistic equation of motion a field $\phi$ can satisfy is the massless Klein-Gordon equation,

\[\partial^{2}\phi=0,\quad \partial^{2}=\partial_ {\mu}\partial^{\mu}=\partial_ {t}^{2}-\nabla^{2}.\]Decompose $\phi$ into a continuum of momentum mode, each mode can be written as

\[a_ {p} (t) e^{ i\vec{p}\cdot \vec{x} }\]where we have assume the separation of variable $t$ and $\vec{x}$, and the time-dependent part of the Klein-Gordon equation gives

\[(\partial_ {t}^{2}+\vec{p}\cdot \vec{p})a_ {p} (t) = 0\]with solutions

\[a_ {p} (t) =a_ {p} e^{ \pm i\omega t},\quad \omega^{2}= \vec{p}^{2}.\]where $a_ {p}$ now is just some c-number, constant in time. The field can be expanded as a linear combination of all the momentum modes

\[\phi(t,\vec{r}) = \int \frac{d^{d}p}{(2\pi)^{d} } \, (a_ {p} e^{ -ipx }+a_ {p} ^{\ast }e^{ipx })\]where the second term in the parenthesis is to make sure that $\phi$ is real. We have assembled $\omega$ and $\vec{p}$ into a Lorentzian vector $p=(\omega,\vec{p})$.

Now the second quantization. This is usually first done in the momentum space, since we are treating each mode as a harmonic oscillator. You can already see one aspect of the difference between the previously define lattice quantization and the textbook second quantization. We introduce the equal-time commutation relation

where we have omitted the vector sign in the superscript $k,p$ to avoid overly cumbersome notation. The factors of $2\pi$ are a convention, stemming from our convention for Fourier transform, for the details see my other blog on conventions.

We want the operators $a_ {p}^{\dagger}$ to create particles with momentum $\vec{p}$. Let $\left\lvert{\vec{p} }\right\rangle$ be a physical state with a single particle with momentum $\vec{p}$, define

\[a_ {p} ^{\dagger}\left\lvert{\Omega}\right\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{ 2\omega _ {p} } }\left\lvert{\vec{p} }\right\rangle ,\]where $\left\lvert{\Omega}\right\rangle$ is the ground state in the vacuum sector. This factor of $1 / \sqrt{ 2\omega _ {p} }$ is just another convention.

From the normalization $\left\langle \Omega \middle\vert \Omega \right\rangle=1$ and the commutation of $a,a^{\dagger}$ we get

\[\left\langle \vec{p} \middle\vert \vec{k} \right\rangle =2\omega _ {p} (2\pi)^{d}\delta^{d}(\vec{p}-\vec{k}).\]As a result, the identity operator for one particle states is

\[\mathbb{1}=\int \frac{d^{d}p}{(2\pi)^{d} } \, \frac{1}{2\omega _ {p} }\left\lvert{\vec{p} }\right\rangle \left\langle{\vec{p} }\right\rvert .\]We define the quantum field as integrals over $a_ {p}$ and $a_ {p}^{\dagger}$,

\[\phi_ {0}(\vec{x})= \int \frac{d^{d}p}{(2\pi)^{d} } \, \frac{1}{\sqrt{ 2\omega } } (a_ {p} e^{ i\vec{p} \cdot \vec{x} } + a_ {p} ^{\dagger}e^{ -i\vec{p}\cdot \vec{x} })\]where the subscript $0$ indicates this is a free field. The traditional view is to take it as the definition of the field operator $\phi_ {0}$ constructed from the creation and annihilation operators $a_ {p}$ and $a_ {p}^{\dagger}$ (Schwartz M.D.), but we shall try an opposite viewpoint, as will be shown later.

Later we will work with the Schrodinger picture which is less commonly used compared to the Heisenberg or interaction pictures. To finish the review on the second quantization, we just mentioned that in Heisenberg picture, all the time dependence is in operators such as $\phi$ and $a_ {p}$, the field operator reads

\[\phi_ {0}(\vec{x},t) = \int \frac{d^{d}p}{(2\pi)^{d} } \, \frac{1}{\sqrt{ 2\omega _ {p} } }(a_ {p} e^{ -ipx } + a_ {p} ^{\dagger}e^{ ipx }),\]which is not Lorentz invariant.

Instead of the traditional view of harmonic oscillator quantization in the momentum space, let’s take Eq.(2) as the starting point. Adopt a somewhat un-conventional field expansion

\[\begin{align*} \phi(\vec{x}) &= \int \frac{d^{d}p}{(2\pi)^{d} } \, e^{ -i\vec{x}\cdot \vec{p} }\phi_ {p},\\ \pi(\vec{x}) &= \int \frac{d^{d}p}{(2\pi)^{d} } \, e^{ -i \vec{x}\cdot \vec{p} }\pi_ {p}. \end{align*}\]The next question is how to inverse it on a lattice…

2.4 Kink in (2+1)-dimension

If we adopt (1) the ultraviolet cutoff $\Lambda$ and (2) the harmonic quantization in the trivial vacuum sector and translate it to the physical spacetime. As a result we get a non-local commutation relation in spacetime,

\[[\phi(x),\pi(y)]_ {\Lambda} = i \int_{-\Lambda}^{\Lambda} \frac{dp}{2\pi} \, e^{ -ip(x-y)} = i \frac{\sin(\Lambda x)}{\pi x} .\]This is non-local in the sense that for certain $x\neq y$ the commutator is nonzero. However, this commutation relation does agree with the lattice picture, if we set the lattice spacing to be $\pi / \Lambda$! (check for yourself)

But for now let’s forget about the momentum cutoff and work with a more general picture. We can define the normal ordering in the vacuum sector, then propagate it to the kink sector via the displacement operator, which we will talk about shortly.

Recall the equation of motion reads

\[\partial^{2}\phi-\frac{1}{\lambda} \frac{dV(\sqrt{ \lambda }\phi)}{d\phi}=0,\]separate $\phi(\vec{x},t)$ into the kink background $f(\vec{x})$ and the fluctuation (time-dependent) ${\mathfrak g}$,

\[\phi(\vec{x},t) = f(\vec{x})+{\mathfrak g}(\vec{x},t),\]insert it into the equation of motion and use the fact that $f(\vec{x})$ satisfies the time-independent EoM, we get the EoM for the fluctuation field:

\[\begin{align*} 0 &= \partial^{2} (f+{\mathfrak g}) -\frac{1}{\lambda} \frac{d V(\sqrt{ \lambda }(f+{\mathfrak g}))}{d\phi} \\ &= \partial^{2} f + \partial^{2}{\mathfrak g}-\frac{1}{\lambda} \frac{d}{d\phi}\left( V( \sqrt{ \lambda } f)+{\mathfrak g} \frac{dV(\sqrt{ \lambda }\phi)}{d\phi} \mid_ {\phi=f} + \mathcal{O}({\mathfrak g^{2} }) \right) \\ &= \partial^{2} f - \frac{1}{\lambda} \frac{dV(\sqrt{\lambda} f)}{df} + \partial^{2}{\mathfrak g}-\frac{ {\mathfrak g} } {\lambda} \frac{d^{2}V(\sqrt{\lambda}f)}{d f^{2} } +\mathcal{O}( {\mathfrak g}^{2} ) \\ &= \partial^{2} {\mathfrak g}+V^{(2)}(\sqrt{ \lambda }f) + \mathcal{O}({\mathfrak g}^{2}), \end{align*}\]where

\[V^{(n)} := \frac{d^{n}V(\tilde{\phi})}{d\tilde{\phi}^{n} },\quad \tilde{\phi}:=\sqrt{ \lambda }\phi.\]In the below are some results needed for the derivation, not carefully organized in a readable order. I will tidy it up later.

The commutation relation reads

\[[\phi(\vec{x}_ {1}),\pi(\vec{x}_ {2})] = i \delta^{d}(\vec{x}_ {1}-\vec{x}_ {2}),\]together with the decomposition we have

\[\begin{align*} [\phi_ {p_ {1} },\pi_ {p_ {2} }] &= i(2\pi)^{d}\delta^{d}(p_ {1}+p_ {2}),\\ [\phi_ {k_ {1} },\pi_ {k_ {2} }] &= i(2\pi)^{d}\delta^{d}(k_ {1}+k_ {2}), \end{align*}\]note the plus sign instead of minus in the parenthesis.

The decomposition into ladder operators reads

\[\begin{align*} \phi_ {p} &= A^{\ddagger}_ {p}+\frac{A_ {-p} }{2\omega_ {p} },\quad \pi_ {p}=i\omega_ {p}A^{\ddagger}_ {p}- \frac{iA_ {-p} }{2},\quad A^{\ddagger}_ {p} = \frac{A^{\dagger}_ {p} }{2\omega _ {p} },\\ \phi_ {k} &= B^{\ddagger}_ {k}+\frac{B_ {-k} }{2\omega_ {k} },\quad \pi_ {k}=i\omega_ {k}B^{\ddagger}_ {k}- \frac{iB_ {-k} }{2},\quad B^{\ddagger}_ {k} = \frac{B^{\dagger}_ {k} }{2\omega _ {k} }. \end{align*}\]The commutation relation in terms of those reads

\[[B_ {k_ {1} },B^{\ddagger}_ {k_ {2} }] = (2\pi)^{d}\delta^{d}(k_ {1}-k_ {2}).\]Note the minus sign. It is exactly the same as what we’ve got in the trivial vacuum sector where

\[[A_ {p_ {1} },A^{\ddagger}_ {p_ {2} }] = (2\pi)^{d}\delta^{d}(p_ {1}-p_ {2}).\]Expand $A,A^{\ddagger}$ in terms of $B,B^{\ddagger}$ we have

\[\begin{align*} A^{\ddagger}_ {p} &= \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \; \frac{d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{d} } \, \frac{\tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k}(-\vec{p})}{2\omega_ {p} } \left[ (\omega_ {p} +\omega _ {k} )B_ {k} ^{\ddagger}+(\omega _ {p} -\omega _ {k} )\frac{B_ {-k} }{2\omega_ {k} } \right] ,\\ A_ {-p}&= \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \; \frac{d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{d} } \, \tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k}(-\vec{p}) \left[ (\omega _ {p} -\omega _ {k} ) B_ {k} ^{\ddagger}+(\omega _ {p} +\omega _ {k} )\frac{B_ {-k} }{2\omega _ {k} } \right]. \end{align*}\]The idea is to

- write terms in the Hamiltonian in normal order with respect to $A,A^{\ddagger}$,

- use the above relation to rewrite it in terms of $B,B^{\ddagger}$,

- use the commutation relation to diagonalize $H$ in terms of $B,B^{\ddagger}$.

The normal ordered leading order Hamiltonian (in kink sector) reads

\(H'_ {2} = A+B+C\) where

\[\begin{align*} A &= \frac{1}{2} \int d^{d}x \, :\pi^{2}(\vec{x}):_ {a}, \\ B &= \frac{1}{2} \int d^{d}x \, :(\nabla\phi(\vec{x}))^{2}:_ {a}, \\ C &= \frac{1}{2} \int d^{d}x \, V^{(2)} (\sqrt{ \lambda }f) :\phi^{2}(\vec{x}):_ {a}. \end{align*}\]In plane-wave space and $\vec{k}$-space we have

\[\begin{align*} A &= \frac{1}{2} \int\frac{d^{d}p}{(2\pi)^{d}} \, :\pi_ {p}\pi_ {-p}:_ {a} , \\ B+C &= \frac{1}{2} \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \;\frac{d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{d}} \, \omega^{2}_ {k} \int \frac{d^{d}p_ {1}}{(2\pi)^{d}} \int \frac{d^{d}p_ {2}}{(2\pi)^{d}} \, \tilde{ {\mathfrak g}}_ {-k}(\vec{p}_ {1}) \tilde{ {\mathfrak g}}_ {k}(\vec{p}_ {2}) :\phi_ {p_ {1}}\phi_ {p_ {2}}:_ {a}. \end{align*}\]Define the Fourier transformation $\tilde{f}$ of function $f(x)$ to be

\[\tilde{f}(\vec{p}) := \int d^{d}x \, f(\vec{x})e^{ -i\vec{p}\cdot \vec{x} }.\]The Fourier transformation of normal modes reads

\[\tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k}(p) = \int d^{d} x \, {\mathfrak g}_ {k}( \vec{x} ) e^{-i\vec{p} \cdot \vec{x} }\]which satisfies relation

\[\tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k}^{\ast}(\vec{p}) = \tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {-k}(-\vec{p}) .\]Sometime this relation can help to make the numerical calculation easier.

The normalization relations for ${\mathfrak g}$ reads

\[\begin{align*} \int d^{d}x \, {\mathfrak g}^{\ast }_ {k}(\vec{x}){\mathfrak g}_ {k'}(\vec{x}) &=(2\pi)^{d}\delta ^{d}(\vec{k}-\vec{k}'), \\ \int \frac{d^{d}p}{(2\pi)^{d} } \tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k}(\vec{p}) \tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k'}(\vec{p}) &= (2\pi)^{d}\delta ^{d}(\vec{k}+\vec{k}'), \\ \int \frac{d^{d}p}{(2\pi)^{d} } \tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k}(\vec{p}) \tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }^{\ast }_ {k'}(\vec{p}) &= (2\pi)^{d}\delta ^{d}(\vec{k}-\vec{k}') , \end{align*}\]and the completeness condition (in both spacetime and momentum space)

\[\begin{align*} \int \frac{d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{2}} \, {\mathfrak g}_ {k}(\vec{x}) {\mathfrak g}^{\ast }_ {k}(\vec{y}) &=\delta ^{d}(\vec{x}-\vec{y}), \\ \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \; \frac{d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{d}} \, \tilde{ {\frak g} }_ {k}(\vec{p}_ {1}) \tilde{ {\frak g} }^{\ast} _ {k}(\vec{p}_ {2}) &= (2\pi)^{d} \delta^{d}(\vec{p}_ {1} - \vec{p}_ {2}). \end{align*}\]Note that in our convention of Fourier transformation, instead of $+i\vec{p}\cdot \vec{x}$ we have minus sign. This is only the spatial part of the Fourier transformation (recall that our spacetime is $d+1$ dimensional).

We have divided the leading order, kink-sector Hamiltonian into $A+B+C$ three parts, in normal order we have

\[\begin{align*} A &=\frac{1}{2} \int \frac{d^{d}p}{(2\pi)^{d} } \, \left( -\omega^{2}_ {p} A^{\ddagger}_ {p} A^{\ddagger}_ {-p}+ \omega _ {p} A^{\ddagger}_ {p} A_ {p} -\frac{1}{4} A_ {-p}A_ {p} \right), \\ B+C &= \frac{1}{2} \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \;\frac{d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{d} } \int \frac{d^{d}p}{(2\pi)^{d} } \frac{d^{d}p'}{(2\pi)^{d} } \,\omega_ {k}^{2}\, \tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {-k}(\vec{p} )\tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k}(\vec{p}') \\ &\;\;\;\; \times \left[ A^{\ddagger}_ {p }A^{\ddagger}_ {p'} + \frac{A^{\ddagger}_ {p }A_ {-p'} }{2\omega_ {p'} } + \frac{A^{\ddagger}_ {p'}A_ {-p } }{2\omega_ {p } } + \frac{A_ {-p } }{2\omega_ {p } } \frac{A_ {-p'} }{2\omega_ {p'} } \right]. \end{align*}\]In the calculation just keep in mind the property of $\tilde{ {\mathfrak g}}$ and invariance under combined exchange $p \leftrightarrow p’$ with $k \to -k$.

The following relations are useful in derivation, with terms that do not annihilate the kink ground state $\left\lvert{0}\right\rangle$:

\[\begin{align*} A^{\ddagger}_ {p} A^{\ddagger}_ {p'} &\cong \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \frac{d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{d} } \frac{d^{d}k'}{(2\pi)^{d} } \frac{\tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k}(-\vec{p}) \tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k'}(-\vec{p}')}{2\omega_ {p} 2\omega_ {p'} } \\ &\;\;\;\;\; \times \left( (\omega _ {p} +\omega _ {k} )(\omega_ {p'}+\omega_ {k'})B^{\ddagger}_ {k} B^{\ddagger}_ {k'}+ \frac{1}{2\omega _ {k} }(\omega _ {p} -\omega _ {k} )(\omega_ {p'}+\omega_ { {k'} }) B_ {-k} B^{\ddagger}_ {k'}) \right), \\ A^{\ddagger}_ {p} A_ {-p'} &\cong \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \frac{d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{d} } \frac{d^{d}k'}{(2\pi)^{d} } \frac{1}{2\omega_ {p} } \tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k}(-\vec{p})\tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k'}(-\vec{p}') \\ &\;\;\;\;\; \times \left( (\omega _ {p} +\omega _ {k} )(\omega_ {p'}-\omega_ {k'})B^{\ddagger}_ {k} B^{\ddagger}_ {k'}+ \frac{1}{2\omega _ {k} } (\omega _ {p} -\omega _ {k} )(\omega_ {p’}-\omega_ { {k'} }) B_ {-k}B^{\ddagger}_ {k'}) \right), \\ A_ {-p} A_ {-p'} &\cong \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \frac{d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{d} }\frac{d^{d}k'}{(2\pi)^{d} } \tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k}(-\vec{p})\tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k'}(-\vec{p}')\\ &\;\;\;\;\; \times \left( (\omega _ {p} -\omega _ {k} )(\omega_ {p'}-\omega_ {k'})B^{\ddagger}_ {k} B^{\ddagger}_ {k'} + \frac{1}{2\omega _ {k} }(\omega _ {p} +\omega _ {k} )(\omega_ {p'}-\omega_ { {k'} }) B_ {-k}B^{\ddagger}_ {k'}) \right). \\ \end{align*}\]We just need to keeps the terms surviving acting on $\left\lvert{0}\right\rangle$, namely the terms that are proportional to $B^{\ddagger} B^{\ddagger}$ and $B B^{\ddagger}$.

The part in $A$ and $B+C$ that are proportional to $B^{\ddagger}B^{\ddagger}$ reads

\[\begin{align*} A &\supset \frac{1}{8} \int \frac{d^{d}p}{(2\pi)^{d} } \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \frac{\;d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{d} } \frac{d^{d}k'}{(2\pi)^{d} } \tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k}(-\vec{p})\tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k'}(\vec{p}) B_ {k}^{^{\ddagger} } B_ {k'}^{\ddagger} \\ &\;\;\;\;\; \times (-4\omega _ {k} \omega_ {k'} + 2\omega _ {p} \omega _ {k} -2\omega _ {p} \omega_ {k'}) \\ &= - \frac{1}{2} \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \, \frac{d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{d} } \, \omega^{2}_ {k}B^{\ddagger}_ {k} B^{\ddagger}_ {-k}, \\ B+C &\supset \frac{1}{2} \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \; \frac{d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{d} } \frac{d^{d}k_ {1} }{(2\pi)^{d} } \frac{d^{d}k_ {2} }{(2\pi)^{d} } \int \frac{d^{d}p_ {1} }{(2\pi)^{d} } \frac{d^{d}p_ {2} }{(2\pi)^{d} } \\ & \;\;\;\;\; \times \omega^{2}_ {k} \, \tilde{\mathfrak g}_ {k_ {1} }(-\vec{p}) \tilde{\mathfrak g}_ {k_ {2} }(-\vec{p}') \tilde{\mathfrak g}_ {-k}(\vec{p}) \tilde{\mathfrak g}_ {k}(\vec{p}') B^{\ddagger}_ {k_ {1} }B^{\ddagger}_ {k_ {2} } \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \frac{d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{d} } \,\omega _ {k} ^{2} B^{\ddagger}_ {k}B^{\ddagger}_ {-k} . \end{align*}\]Note that the last two terms in the second line cancel each other since $k,k’$ are dummy indices, we can simply exchange them. We have used the normalization condition for $\tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }$ functions. Apparently, put together, in $A+B+C$ the terms proportions to $B^{\ddagger}B^{\ddagger}$ disappear! We are left with terms proportional to $B B^{\ddagger}$ only, which can be obtained similarly. We will omit the explicit result here since it can be easily found in other papers.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: