Note on the kink mass correction in 3D Part II

1. Domain wall in phi-fourth model

Recall that we are working in $D = d+1$ dimensional space-time, the space-dimension is $d$. For now let’s consider $d=2$. In 2-dimensional space, a kink can extend to form a domain wall, for more info about domain walls see my other note. The world line of such a domain wall would be world sheet. Now let’s try to calculate the quantum corrections to the tension of such a domain wall.

The energy is given by the space integral of the Hamiltonian density,

\[H = \int d^{d}x \, \mathcal{H},\quad \mathcal{H} = \frac{1}{\lambda}\left[ \frac{\tilde{\pi}^{2}}{2}+\frac{(\nabla \tilde{\phi})^{2}}{2} + V(\tilde{\phi}) \right]\]where

\[\tilde{\phi}:= \sqrt{ \lambda } \phi,\quad \tilde{\pi} := \sqrt{ \lambda } \pi .\]Note that we have written $\phi$ as $\tilde{\phi}$ so that the coupling becomes an overall pre-factor. Keep in mind that, in this formalism, the energy is no longer simply $H=\int \, V$ but $H = \int \, V / \lambda$.

Let the spatial coordinates be $x$ and $y$. Consider the potential (expanded in the negative vacuum)

\[V(\tilde{\phi}) = \frac{\tilde{\phi}^{2}}{4} (\tilde{\phi}-\sqrt{ 2 }m)^{2}.\]Now consider a flat domain wall in $x=0$ plane. The classical kink solution in the $x$-direction is

\[\widetilde{f}(x,y) = \frac{m}{\sqrt{ 2 }} \left( 1+\tanh \frac{mx}{2} \right)\]where again, $\widetilde{f} = \sqrt{ \lambda }f$ by definition.

The energy now reads

\[H = \int dy \int dx \, \frac{1}{\lambda} \left( \frac{1}{2} (\partial_ {x} \widetilde{f})^{2}+ V(\tilde{f}) \right) =: \int dy \, \rho_ {0}(y),\]where $\rho_ {0}$ is now interpreted as the tension of the domain wall. The calculation is exactly the same as for the kink energy, but to refresh the memory I decided to do it again.

Introduce a new variable $t := \frac{mx}{2}$, we have

\[\widetilde{f}(t) = \frac{m}{\sqrt{ 2 }} (1+\tanh t),\quad dx = \frac{2}{m} dt,\quad \partial_ {x} = \frac{m}{2} \partial_ {t}.\]The potential contribution to the energy is

\[\begin{align*} \int dx \, \frac{1}{\lambda} V(\tilde{f}) &= \frac{m^{3}}{8\lambda}\int dt \, (\tanh ^{2}(t)-1) ^{2}\\ &= \frac{m^{3}}{8\lambda} \int dt \, \frac{1}{\cosh^{4}t} \\ &= \frac{m^{3}}{6\lambda}, \end{align*}\]where we have used

\[\int dt \, \frac{1}{\cosh^{4}t} = \frac{4}{3}.\]Similarly, the contribution from the space-derivative term reads

\[\begin{align*} \frac{1}{\lambda} \int dx \, \frac{1}{2} (\partial_ {x}\widetilde{f})^{2} &= \frac{m^{3}}{8\lambda} \int dt \, (\partial_ {t}\tanh t)^{2} \\ &= \frac{m^{3}}{8\lambda} \int dt \, \frac{1}{\cosh^{4}t} \\ &= \frac{m^{3}}{6\lambda}. \end{align*}\]Putting Eq. (1) and Eq. (2) together, we have

\[\rho_ {0} = \frac{m^{3}}{3\lambda}.\]The dimensional analysis gives us

\[[\lambda] = 4-D = 3-d,\]hence in $2+1$ dimension the coupling has dimension of mass.

2. Normal Modes

Since we assumed the domain wall to be lying flat in the $y$-plane, the normal modes in 2-d space can be factorized into $x$ and $y$ components,

\[{\mathfrak g} _ {k_ {x}k_ {y}} (x,y) = {\mathfrak g}_ {k_ {x}}(x) \times e^{ -i y k_ {y}}.\]The normal modes are the solution of the equation of motion in the kink background, or Poschl-Teller potential. These modes include a continuum

\[{\mathfrak g} _ {k}(x) = \frac{e^{-ikx}}{\omega_ {k} \sqrt{m^2+4k^2}}\left[2k^2-m^2+(3/2)m^2\text{sech}^2(m x/2)-3im k\tanh(m x/2)\right]\]with eigenvalue $\omega_ {k} = \sqrt{ k^{2}+m^{2} }$, a zero mode

\[{\mathfrak g}_ {B} = -\sqrt{ \frac{3m}{8} } \text{sech}^{2}\left( \frac{mx}{2} \right)\]with eigenvalue $0$, and a shape mode

\[{\mathfrak g} _ {S} = \frac{\sqrt{ 3m }}{2} \tanh \frac{mx}{2} \text{sech} \frac{mx}{2},\quad \omega_ {S} = \frac{\sqrt{ 3 }}{2}m\]with eigenvalue less then the rest mass of excited particle.

Momentum in the $y$-direction also contributes to the total energy, putting them together with the zero modes, shape modes and continuum in the $x$ direction we have

\[\boxed { \omega_ {k_ {B}k_ {y}} = \left\lvert k_ {y} \right\rvert ,\quad \omega_ {k_ {S}k_ {y}} = \sqrt{ \frac{3m^{2}}{4}+k_ {y}^{2} },\quad \omega_ {k_ {x} k_ {y}} = \sqrt{ m^{2}+k_ {x}^{2}+k_ {y}^{2} }. }\]Note that

- there is a zero mode corresponding to $k_ {B},k_ {y}=0$,

- the mass gap disappears, due to the mass-gap-less of $y$-momentum.

The formalism we developed in generic dimension $d$ surely also applies to $d=2$. Let $\vec{p}=(p_ {x},p_ {y})$ and $\vec{k}=(k_ {x},k_ {y})$. The Fourier transform is

\[\tilde{\mathfrak{g} }_ {k_ {x},k_ {y}} (\vec{p})= \int d^{2}x \, \mathfrak{g} _ {k}(\vec{x}) e^{ -i\vec{k}\cdot \vec{x} } = (2\pi)\delta(k_ {y}+p_ {y}) \times \tilde{\mathfrak{g}} _ k (p_ {x}).\]Again we see the factorization in $x$ and $y$, the $\delta$-function in $y$ direction is due to the plane wave expansion.

Note that the infinite volume of a flat $\mathbb{R}$ can be written as Dirac-$\delta$ function $\delta(0)$. To see it, recall the Fourier transform of a function is written as

\[\widetilde{f}(\vec{k}) = \int d^{d}x \, e^{ -i\vec{k}\cdot \vec{x} } f(\vec{x})\]which means if we set $f(\vec{x})=1$ then

\[\tilde{f}(\vec{k}) = \int d^{d}x \, e^{ -i \vec{k}\cdot\vec{x} } = (2\pi)^{d} \delta^{d}(k),\]If we further set $k=0$ then the integral becomes

\[\int d^{d}x \, 1\, = \text{Vol}^{d} = (2\pi)^{d}\delta^{d}(0).\]In the case of 1-dimension, say coordinated by $y$, the total length would be $2\pi \delta(0)$.

This identity comes in handy when we take the factorized expression Eq. (3) into the one-loop correction

\[\begin{align*} Q_ {1} &= -\frac{1}{4} \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \frac{\;d^{2}k}{(2\pi)^{2}} \, \int \frac{d^{2}p}{(2\pi)^{2}} \, \left\lvert \tilde{ \mathfrak{g} }_ {k}(\vec{p}) \right\rvert^{2} \frac{(\omega_ {k}-\omega_ {p})^{2}}{\omega_ {p}} \\ &= -\frac{1}{4} \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \frac{\;d^{2}k}{(2\pi)^{2}} \, \int \frac{d^{2}p}{(2\pi)^{2}} \, \left\lvert (2\pi)\delta(k_ {y}+p_ {y})\tilde{ \mathfrak{g} }_ {k}(p_ {x}) \right\rvert^{2} \frac{(\omega_ {k}-\omega_ {p})^{2}}{\omega_ {p}} \\ &= -\frac{1}{4} \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \; \frac{dk_ {x}}{2\pi} \int \frac{dk_ {y}}{2\pi} \int \frac{dp_ {x}}{2\pi} (2\pi)\delta(0)\left\lvert \tilde{\mathfrak{g}}_ {k_ {x}} (p_ {x})\right\rvert ^{2} \frac{(\omega_ {k_ {x} p_ {y}}-\omega_ {p})^{2}}{\omega_ {p}} \\ &= - \frac{L_ {\text{DM}}}{4}\sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \;\frac{dk_ {x}}{2\pi} \int \frac{dk_ {y}}{2\pi} \int \frac{dp_ {x}}{2\pi} \left\lvert \tilde{\mathfrak{g}}_ {k_ {x}} (p_ {x})\right\rvert ^{2} \frac{(\omega_ {k_ {x} p_ {y}}-\omega_ {p})^{2}}{\omega_ {p}} \\ &= L_ {\text{DM}} \times (\text{tension correction}). \end{align*}\]In the above equation we have set the dimensionality $d$ to $2$. $\omega_ {k}$ is the short-handed form for $\omega_ {k_ {x}k_ {y}}$, the same for $\omega_ {p}$. Note that starting from the third line, we have $\omega_ {k}=\omega_ {k_ {x} p_ {y}}$ due to the Dirac-$\delta$ function. The integral regarding $y$-coordinate gives as a term proportional to $(2\pi)\delta(0)$, which is the total length of the $y$-direction. $L_ {\text{DM}}$ is the length of the domain wall, $L_ {\text{DM}}=\int dy$. It is understood that in the final result $p_ {y}=-k_ {y}$. It agrees with our naive expectation that the correction is proportional to the total length of the domain wall.

Eq. (4) can also be written as

\[\begin{align*} Q_ {1} &= -\frac{1}{4} \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \; \frac{dk_ {x}}{2\pi} \int \frac{dp_ {x}}{2\pi} \int \frac{dp_ {y}}{2\pi} (2\pi)\delta(0)\left\lvert \tilde{\mathfrak{g}}_ {k_ {x}} (p_ {x})\right\rvert ^{2} \frac{(\omega_ {k}-\omega_ {p})^{2}}{\omega_ {p}} \\ &= - \frac{L_ {\text{DM}}}{4}\sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \;\frac{dk_ {x}}{2\pi} \int \frac{dp^{2}}{(2\pi)^{2}} \left\lvert \tilde{\mathfrak{g}}_ {k_ {x}} (p_ {x})\right\rvert ^{2} \frac{(\omega_ {k}-\omega_ {p})^{2}}{\omega_ {p}} \\ &= \int dy \, \left( - \frac{1}{4} \right)\sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \;\frac{dk_ {x}}{2\pi} \int \frac{dp^{2}}{(2\pi)^{2}} \left\lvert \tilde{\mathfrak{g}}_ {k_ {x}} (p_ {x})\right\rvert ^{2} \frac{(\omega_ {k}-\omega_ {p})^{2}}{\omega_ {p}} \\ &= : \int dy \, \rho_ {1}(y). \end{align*}\]Here again $\omega_ {k}$ is understood to be $\omega_ {k_ {x} k_ {y}}$, and we have defined the one-loop correction $\rho_ {1}$ to the tension. Note that one-loop correction comes not from the interaction, as in QFT models in the vacuum sector, but rather comes from the non-trivial soliton background.

3. Fourier Transform

We still need to evaluate the one-loop correction

\[\boxed { \rho_ {1} = \left( - \frac{1}{4} \right)\sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \;\frac{dk_ {x}}{2\pi} \int \frac{dp^{2}}{(2\pi)^{2}} \left\lvert \tilde{\mathfrak{g}}_ {k_ {x}} (p_ {x})\right\rvert ^{2} \frac{(\omega_ {k}-\omega_ {p})^{2}}{\omega_ {p}}. }\]To do this, first we need to Fourier-Transform various normal modes.

To Fourier transform it we use Mathematica. In Mathematica, the convention used for the Fourier transform is represented by the function FourierTransform[expr, t, ω], where expr is the expression to be transformed, t is the time variable, and ω is the frequency variable. This gives the symbolic Fourier transform of the expression. For multidimensional Fourier transforms, you can use FourierTransform[expr, {t1, t2, …}, {ω1, ω2, …}], but here we won’t need it.

The basis function used by Mathematica’s FourierTransform is dependent on the FourierParameters setting. The FourierParameters option is specified as {a, b}, where a and b are parameters that influence the Fourier transform’s definition. Specifically, they appear in the exponential factor and the normalization constant of the Fourier transform equations. The default setting for FourierParameters in Mathematica is {0, 1}, which corresponds to using the basis function $e^{i t \omega}$ for the Fourier transform,

where $\mathcal{F}\left\lbrace f \right\rbrace$ is the Fourier transform of function $f(t)$. In general, under FourierParameters->{a,b} the Fourier Transform is set to be

In order to change it to our desired basis, we need to set $a=1,b=-1$, which is the so-called physics convention. As a test let’s try to transform a plane wave $\exp(-ipx)$, with our convention mathematica should return $2\pi \delta(p+k)$. The code reads

FourierTransform[Exp[-I p x], x, k, FourierParameters -> {1, -1}]

which indeed returns 2 Pi DiracDelta[k + p].

The shape mode

The shape mode as a function of $x$ reads

\[{\mathfrak g} _ {S}(x) = \frac{\sqrt{ 3m }}{2} \tanh \frac{mx}{2} \text{sech} \frac{mx}{2},\]whose Fourier transform can be calculated with mathematica code

fkgS[x_] := Sqrt[3 m]/2 Tanh[(m x)/2] Sech[ (m x)/2];

FourierTransform[fkgS[x], x, p, FourierParameters -> {1, -1}]

The result reads

\[\boxed { \tilde{ \mathfrak{g} }_ {S}(p) = -\frac{2i\sqrt{ 3 }\pi p}{m^{3/2}} \mathrm{sech}\left( \frac{p\pi}{m} \right). }\]The zero mode

From the following Mathematica code

fkgB[x_] := -Sqrt[((3 m)/8)] Sech[(m x)/2]^2;

FourierTransform[fkgB[x], x, k, FourierParameters -> {1, -1}]

we have

\[\boxed { \tilde{ \mathfrak{g} }_ {B}(p) = -\frac{\sqrt{ 6 }\pi p}{m^{3/2}}\text{csch}\left(\frac{\pi p}{m} \right) }\]The continuum

The Fourier transform is given by the following Mathematica code,

fkgk[x_] :=E^(-I k x)/(\[Omega]k Sqrt[m^2+4k^2])(2k^2-m^2+3/2 m^2 Sech[(m x)/2]^2 - 3I m k Tanh[(m x)/2]);

FourierTransform[fkgk[x], x, p, FourierParameters -> {1, -1}]

which gives us

\[\tilde{ \mathfrak{g} }_ {k}(p) = \frac{6\pi p}{\omega_ {k}\sqrt{ 4k^{2} + m^{2} }} \text{csch}\left(\frac{(k+p)\pi}{m}\right).\]However, if we perform the Fourier transform term-by-term we get

In[1]:= FourierTransform[E^(-I k x)/(\[Omega]k Sqrt[m^2 + 4 k^2]) (2 k^2 - m^2), x, p,

FourierParameters -> {1, -1}]

Out[1]= (2 (2 k^2 - m^2) \[Pi] DiracDelta[k + p])/(Sqrt[4 k^2 + m^2] \[Omega]k)

In[2]:= FourierTransform[E^(-I k x)/(\[Omega]k Sqrt[m^2 + 4 k^2]) (3/2 m^2 Sech[(m x)/2]^2), x, p,

FourierParameters -> {1, -1}]

Out[2]= (6 (k + p) \[Pi] Csch[((k + p) \[Pi])/m])/(Sqrt[4 k^2 + m^2] \[Omega]k)

In[3]:= FourierTransform[E^(-I k x)/(\[Omega]k Sqrt[m^2 + 4 k^2]) (-3 I m k Tanh[(m x)/2]), x, p,

FourierParameters -> {1, -1}]

Out[3]= -((6 k \[Pi] Csch[((k + p) \[Pi])/m])/(Sqrt[4 k^2 + m^2] \[Omega]k))

Putting them together we get

\[\tilde{ \mathfrak{g} }_ {k}(p) = \frac{6\pi p}{\omega_ {k}\sqrt{ 4k^{2} + m^{2} }} \text{csch}\left(\frac{(k+p)\pi}{m}\right)+\frac{2\pi(2k^{2}-m^{2})}{\omega_ {k}\sqrt{ 4k^{2} + m^{2} }} \delta(p+k).\]I have no idea why this delta function disappeared. Any help here?

Let’s proceed to calculate $\rho_ {1}$. Since $k_ {x}$ is separated into three parts, i.e. zero mode, shape mode and continuum, we can separate $\rho_ {1}$ into three corresponding parts, writing

\[\rho_ {1} = \rho_ {1B} + \rho_ {1S} + \int \frac{dk_ {x}}{2\pi} \, \rho_ {1k_ {x}}\]where

\[\begin{align*} \rho_ {1B} &= - \frac{1}{4} \int \frac{dp_ {x}}{2\pi} \, (\tilde{ \mathfrak{g} }_ {B}(p_ {x}))^{2} \int \frac{dp_ {y}}{2\pi}\, \frac{(\omega_ {k_ {B}p_ {y}}-\omega_ {p_ {x}p_ {y}})^{2}}{\omega_ {p_ {x}p_ {y}}}, \\ \rho_ {1S} &= -\frac{1}{4} \int \frac{dp_ {x}}{2\pi} \, (\tilde{ \mathfrak{g} }_ {S}(p_ {x}))^{2} \int \frac{dp_ {y}}{2\pi} \, \frac{(\omega_ {k_ {S}p_ {y}}-\omega_ {p_ {x}p_ {y}})^{2}}{\omega_ {p_ {x}p_ {y}}}, \\ \rho_ {1C} &= \int \, \frac{dk_ {x}}{2\pi} \left( - \frac{1}{4} \right) \int \frac{dp_ {x}}{2\pi}\, \left\lvert \tilde{\mathfrak{g}}_ {k_ {x}} (p_ {x})\right\rvert ^{2} \int \frac{dp_ {y}}{2\pi} \, \frac{(\omega_ {k_ {x}p_ {y}}-\omega_ {p_ {x}p_ {y}})^{2}}{\omega_ { p_ {x}p_ {y}}} \\ &=: \int \frac{dk_ {x}}{2\pi} \, \rho_ {1k_ {x}}. \end{align*}\]The subscript $C$ in $\rho_ {1C}$ stands for continuum.

We have separated the integral over $d^{2}p$ into its two components for a reason, so we can perform the integral over the flat direction $p_ {y}$ analytically first. For the sake of convenience let’s define a general integral of form

\[\mathcal{I} (a,b) := \int_ {-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{d p}{2\pi} \, \frac{(\sqrt{ a+p^{2} }-\sqrt{ b+p^{2} })^{2}}{\sqrt{ b+p^{2} }} ,\]With the help of mathematica again we get

\[\mathcal{I} (a,b) = \frac{a}{2\pi} \left( \frac{b}{a}-\ln \left\lvert \frac{b}{a} \right\rvert -1 \right).\]This form shows that if $a=b$ then $\mathcal{I}_ {ab}=0$, as it should be by definition. If we allow the parameters of $\ln$ function to be dimensionful, another form is more useful to us,

\[\boxed { \mathcal{I} (a,b) = \frac{1}{2\pi} (b-a-a\ln \left\lvert b \right\rvert +a\ln \left\lvert a \right\rvert ). }\]This form made obvious that $\mathcal{I}(a,b)$ behaviors nice at $a=0$.

To calculate Eq. (6), recall that (since $k_ {y}=-p_ {y}$)

\[\boxed { \omega_ {k_ {B}p_ {y}} = \left\lvert p_ {y} \right\rvert ,\quad \omega_ {k_ {S}p_ {y}} = \sqrt{ \frac{3m^{2}}{4}+p_ {y}^{2} },\quad \omega_ {k_ {x} p_ {y}} = \sqrt{ m^{2}+k_ {x}^{2}+p_ {y}^{2} }. }\]We have

\[\begin{align*} \rho_ {1B} &= - \frac{1}{4} \int \frac{dp_ {x}}{2\pi} \, (\tilde{ \mathfrak{g} }_ {B}(p_ {x}))^{2} \int \frac{dp_ {y}}{2\pi}\, \frac{(\omega_ {k_ {B}p_ {y}}-\omega_ {p_ {x}p_ {y}})^{2}}{\omega_ {p_ {x}p_ {y}}}, \\ &= - \frac{1}{4} \int \frac{dp_ {x}}{2\pi} \, (\tilde{ \mathfrak{g} }_ {B}(p_ {x}))^{2} \mathcal{I}(0,m^{2}+p^{2}_ {x}) \\ &= - \frac{1}{4} \int \frac{dp_ {x}}{2\pi} \, (\tilde{ \mathfrak{g} }_ {B}(p_ {x}))^{2} \frac{m^{2}+p^{2}_ {x}}{2\pi} \\ &= - \frac{1}{8\pi} \int \frac{dp_ {x}}{2\pi} \, (\tilde{ \mathfrak{g} }_ {B}(p_ {x}))^{2} (m^{2}+p^{2}_ {x})\\ &= -\frac{3 m^2}{20 \pi} \end{align*}\]The last line is obtained by Mathematica code

tldgB[p_] := -((Sqrt[6] \[Pi] p) /m^(3/2)) Csch[(p \[Pi])/m];

Integrate[-1/(8 \[Pi]) 1/(2 Pi) tldgB[px]^2 (m^2 + px^2), {px, -\[Infinity], \[Infinity]},

Assumptions -> {m > 0, m \[Element] Reals}]

Next let’s move on to Eq. (7). We have

\[\begin{align*} \rho_ {1S} &= -\frac{1}{4} \int \frac{dp_ {x}}{2\pi} \, \left\lvert \tilde{ \mathfrak{g} }_ {S}(p_ {x}) \right\rvert ^{2} \int \frac{dp_ {y}}{2\pi} \, \frac{(\omega_ {k_ {S}p_ {y}}-\omega_ {p_ {x}p_ {y}})^{2}}{\omega_ {p_ {x}p_ {y}}} \\ &= -\frac{1}{4} \int \frac{dp_ {x}}{2\pi} \, \left\lvert \tilde{ \mathfrak{g} }_ {S}(p_ {x}) \right\rvert ^{2} \, \mathcal{I}\left( \frac{3}{4}m^{2},m^{2}+p_ {x}^{2} \right) \\ &= -\frac{1}{4} \int \frac{dp_ {x}}{2\pi} \, \left\lvert \tilde{ \mathfrak{g} }_ {S}(p_ {x}) \right\rvert ^{2} \, \mathcal{I}\left( \frac{3}{4}m^{2},m^{2}+p_ {x}^{2} \right) \end{align*}\]where

\[\mathcal{I}\left( \frac{3}{4}m^{2},m^{2}+p_ {x}^{2} \right) = \frac{m^{2}}{2\pi} \left[ \frac{1}{4} + \frac{p_ {x}^{2}}{m^{2}} + \frac{3}{4}\ln\left( \frac{3}{4} \right) - \frac{3}{4}\ln\left( 1+\frac{p_ {x}^{2}}{m^{2}} \right) \right].\]We’ll have to turn to numerical calculation now. For the sake of numerical calculation, we better change $p_ {x}$ to something without dimension. Set $t:= p_ {x} / m$, we have

\[\begin{align*} dp_ {x} &= m dt, \\ \tilde{ \mathfrak{g} }_ {S}(t) &= - \frac{2i\sqrt{3} \pi t}{\sqrt{ m }} \mathrm{sech}\,(\pi t), \\ \mathcal{I}(t) &= \frac{m^{2}}{2\pi} \left[ \frac{1}{4} + t^{2} + \frac{3}{4}\ln\left( \frac{3}{4} \right) - \frac{3}{4}\ln\left( 1+ t^{2} \right) \right]. \end{align*}\]All of this gives us

\[\rho_ {1S} = -\frac{1}{4} \int_ {\infty}^{\infty} \frac{m dt}{2\pi} \, \left\lvert \tilde{ \mathfrak{g} }_ {S}(t) \right\rvert^{2} \, \mathcal{I}(t) = -0.00725 m^{2}.\]It is a little harder to do Eq. (8).

\[\begin{align*} \rho_ {1C} &= - \frac{1}{4} \int \, \frac{dk_ {x}}{2\pi} \int \frac{dp_ {x}}{2\pi}\, \left\lvert \tilde{\mathfrak{g}}_ {k_ {x}} (p_ {x})\right\rvert ^{2} \int \frac{dp_ {y}}{2\pi} \, \frac{(\omega_ {k_ {x}p_ {y}}-\omega_ {p_ {x}p_ {y}})^{2}}{\omega_ { p_ {x}p_ {y}}} \\ &= - \frac{1}{4} \int \, \frac{dk_ {x}}{2\pi} \int \frac{dp_ {x}}{2\pi}\, \left\lvert \tilde{\mathfrak{g}}_ {k_ {x}} (p_ {x})\right\rvert ^{2} \, \mathcal{I}(m^{2}+k_ {x}^{2},m^{2}+p_ {x}^{2}) \end{align*}\]where

\[\mathcal{I}(m^{2}+k_ {x}^{2},m^{2}+p_ {x}^{2}) = \frac{1}{2\pi} \left[ p_ {x}^{2}-k_ {x}^{2}+(m^{2}+k_ {x}^{2})\ln\left( \frac{m^{2}+k_ {x}^{2}}{m^{2}+p_ {x}^{2}} \right) \right].\]This leaves

\[\rho_ {1k_ {x}} = - \frac{1}{8\pi} \int \frac{dp_ {x}}{2\pi}\, \left\lvert \tilde{\mathfrak{g}}_ {k_ {x}} (p_ {x})\right\rvert ^{2} \, \left[ p_ {x}^{2}-k_ {x}^{2}+(m^{2}+k_ {x}^{2})\ln\left( \frac{m^{2}+k_ {x}^{2}}{m^{2}+p_ {x}^{2}} \right) \right]\]Now we simply need to substitute

\[\tilde{ \mathfrak{g} }_ {k_ {x}}(p_ {x}) = \frac{6\pi p_ {x}}{\omega_ {k_ {x}}\sqrt{ 4k_ {x}^{2} + m^{2} }} \text{csch}\left(\frac{(k_ {x}+p_ {x})\pi}{m}\right)+\frac{2\pi(2k_ {x}^{2}-m^{2})}{\omega_ {k_ {x}}\sqrt{ 4k_ {x}^{2} + m^{2} }} \delta(p_ {x}+k_ {x}).\]where $\omega_ {k_ {x}} = \sqrt{ m^{2}+k_ {x}^{2} }$. Note that since $\mathcal{I}(m^{2}+k_ {x}^{2},m^{2}+p_ {x}^{2})$ equals to zero when $p=-k$, hence we can discard the $\delta$ term and focus on the $\text{csch}$ term.

Again we have to turn to numerical methods, and again we need to cook up some dimension-less variables from $k_ {x}$ and $p_ {x}$. Define $\kappa:= k_ {x} / m$ and $\rho := p_ {x} / m$, we have

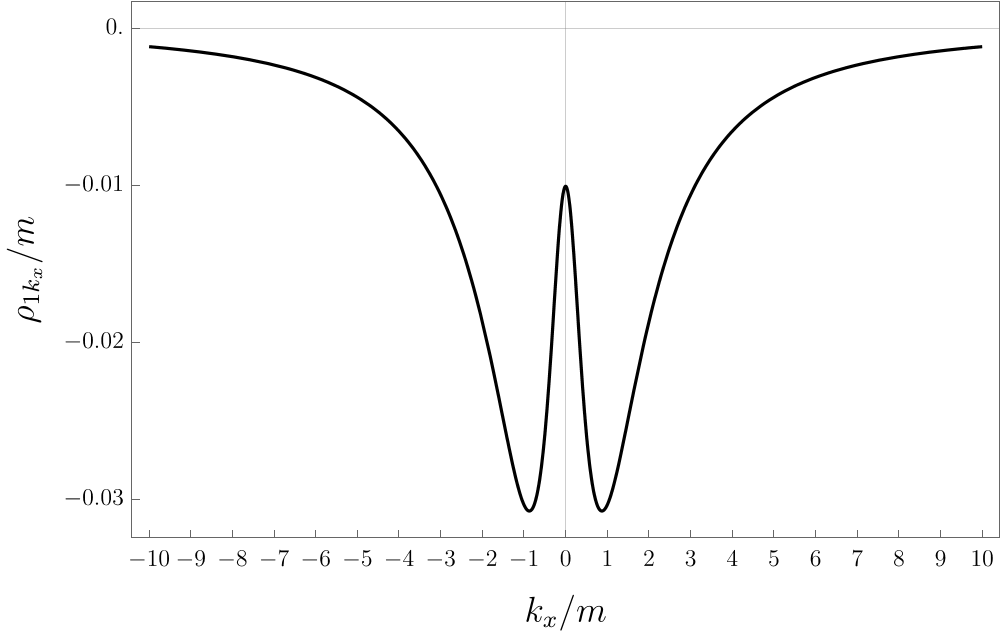

\[\frac{\rho_ {1k_ {x}}(\kappa)}{m} = \int d \rho \, (-9 \rho ^2) \frac{ \left(\left(\kappa ^2+1\right) \log \left(\frac{\kappa ^2+1}{\rho ^2+1}\right)-\kappa ^2+\rho ^2\right) }{4 \left(4 \kappa ^4+5 \kappa ^2+1\right)} \, \text{csch}^2(\pi (\kappa +\rho )).\]The figure of the integral is shown in the below.

The numerical result shows that the total contribution is

\[\rho_ {1C} = -0.0312775 m^{2}\]which is slightly different from that in the draft where $\rho_ {1C}=−0.03156 m^{2}$. We will explain how we get the numerical result and how reliable they are in the following section.

4. Numeric Results

Result Using Mathematica function NIntegral

We can directly perform the double integral over $dk_ {x}dp_ {x}$, based on Eq. (5.18) in the paper. Using the Mathematica code in the following (it is meant to be copied and opened in Mathematica notebook)

Module[{integrandTem},

integrandTem[\[Kappa]_, \[Rho]_] := - (9/(2*4 Pi*(1 + \[Kappa]^2) (1 + 4 \[Kappa]^2))) \[Rho]^2 (Csch[Pi (\[Kappa] + \[Rho])])^2 (-\[Kappa]^2 + \[Rho]^2 - (1 + \[Kappa]^2) Log[(1 + \[Rho]^2)/(1 + \[Kappa]^2)]);

NIntegrate[integrandTem[\[Kappa], \[Rho]], {\[Kappa], -\[Infinity], \[Infinity]}, {\[Rho], -\[Infinity], \[Infinity]}]

]

where $\kappa := k_ {x} / m$ and $\rho := p_ {x} / m$, they are the reduced momenta.

We get -0.0290278 without any error or warning message. However since the slow-converging nature and the fact that the 2D integral domain is infinity, this result is not very reliable, especially it differs from results that we got from more reliable method, which we will elaborate in the following.

When the parameter WorkingPrecision and MaxRecursion is set too high, $50$ for example, the integral result will be unstable and oscillates wildly. It can be seen from running the following code, we will skip the final result rather just mention that it doesn’t work.

Module[{data},

rho1kx[\[Kappa]_] :=

NIntegrate[

integrand[\[Kappa], \[Rho]], {\[Rho], -\[Infinity], \[Infinity]},

WorkingPrecision -> 50, MaxRecursion -> 50, PrecisionGoal -> 50,

AccuracyGoal -> 50];

Plot[rho1kx[\[Kappa]], {\[Kappa], -10, 10}]]

Similarly, PrecisionGoal->50 does not help, for the result is not even monotonically decreasing at large $k_ {x}$, we list the code and the result:

Module[{data},

rho1kx[\[Kappa]_] :=

NIntegrate[

integrand[\[Kappa], \[Rho]], {\[Rho], -\[Infinity], \[Infinity]},

WorkingPrecision -> 50, MaxRecursion -> 50, PrecisionGoal -> 50,

AccuracyGoal -> 50];

data = Table[{\[Kappa], rho1kx[\[Kappa]]}, {\[Kappa], 0, 100, 10}];

TableForm[data,

TableHeadings -> {None, {"\[Kappa]", "rho1kx[\[Kappa]]"}}]]

| $\kappa:=k_ {x} / m$ | $2\pi\rho_ {1k_ {x}}(\kappa)$ |

|---|---|

| 0 | -0.01006749649788711098711857084994935329969685541183878214107904582123515308302 |

| 10 | -0.0011686020701178210972909521296487066189263742489601351585665823047453837217 |

| 20 | -0.00029683035584775581156058547901822136103318225147929961904900419907102724281 |

| 30 | -0.00013231530085233583442497003327532617560145592710253697711716088939790650143 |

| 40 | -0.00007450450777691673214866577793384482867825300381463112353663045604557837695 |

| 50 | -0.00004770576549529244561173447135702738762050345037729455603576967068239692329 |

| 60 | -0.00003313763983924425143831035983787787108360534775902718717778116210540211577 |

| 70 | -3.05720109112434448297096772257979519066270693516655258261985652468392e-67 |

| 80 | -0.00001864475446773486568369540682272388850447396654084892463438555277298711842 |

| 90 | -1.4130111258010705126942302422531874366831796760314017313726306134102608247521657e-56 |

| 100 | -1.08733498976318462751508987228401098685929997485580324213060115407081675e-83 |

It shows wild oscillation, hence is not trust-worthy.

With reasonable options

NIntegrate[

rho1kx[\[Kappa]]/(2 Pi), {\[Kappa], -\[Infinity], \[Infinity]},

WorkingPrecision -> 30, PrecisionGoal -> 6, AccuracyGoal -> 6

]

we get the following result:

NIntegratefailed to converge to prescribed accuracy after 9 recursive bisections in [Kappa] near {[Kappa]} = {169.954045306876363791355871581}.NIntegrateobtained -0.0313611336264321023970618041371 and 2.68446200766726199070353491885 * 10^-6 for the integral and error estimates”.

Which translates to $\boxed {-0.031361 \pm 0.0000027}$. However, the origin of this error estimation is unclear to me, and multiple warnings about converging too slowly make it even less convincing. This motivates us to try another more direct but more controllable method to perform the integral.

Cutoff on $\rho$-integral

Let’s take a closer look at the integral Eq. (9). The integrand contains a factor roughly $\text{csch}^{2}(\kappa+\rho )$, proportional to $e^{-2 (\kappa+\rho) }$, a exponential suppression. When $\kappa$ is fixed, the only integral domain that contributes to the integral is $\rho \in (\kappa-\Lambda,\kappa+\Lambda)$ for some cutoff $\Lambda$. The below numerical results will show that it is sufficient for $\Lambda=4$. We compare the integrals with and without a cutoff, and calculate the numerical difference. The Mathematica code is as follow.

(*cut_:4 means the defalut value for cut is 4, which is used unless \

an explicit value is provided for cut in the function call. rho1kxCut \

can be called as, for example, rho1kxCut[0] or rho1kxCut[0,6] *)

integrand[\[Kappa]_, \[Rho]_] := -((

9 \[Rho]^2 Csch[\[Pi] (\[Kappa] + \[Rho])]^2 (-\[Kappa]^2 + \

\[Rho]^2 + (1 + \[Kappa]^2) Log[(1 + \[Kappa]^2)/(1 + \[Rho]^2)]))/(

4 (1 + 5 \[Kappa]^2 + 4 \[Kappa]^4)));

rho1kxCut[\[Kappa]_, cut_ : 4] :=

NIntegrate[

integrand[\[Kappa], \[Rho]], {\[Rho], -\[Kappa] - cut, -\[Kappa] +

cut}];

Module[{data},

rho1kxOld[\[Kappa]_] :=

NIntegrate[

integrand[\[Kappa], \[Rho]], {\[Rho], -\[Infinity], \[Infinity]}];

data = Table[{\[Kappa],

rho1kxCut[\[Kappa]], (rho1kxCut[\[Kappa]] - rho1kxOld[\[Kappa]])/

rho1kxOld[\[Kappa]]}, {\[Kappa], 0, 70, 5}];

Labeled[

TableForm[data,

TableHeadings -> {None, {"\[Kappa]", "rho1kxCut[\[Kappa]]",

"Relative Error"}}],

"\[Rho]\[Element](-\[Kappa]-4,-\[Kappa]+4)", Top]

]

The result is shown in the following, where relative error is defined as $(\text{cut}-\text{uncut})/\text{cut}$.

$\rho \in(\kappa-4,\kappa+4)$

| $\kappa$ | rho1kxCut | Relative Error |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | -0.0100675 | -8.70642e-7 |

| 5 | -0.00439214 | -3.62796e-9 |

| 10 | -0.0011686 | -3.03801e-9 |

| 15 | -0.000525522 | -2.66222e-9 |

| 20 | -0.00029683 | -2.60459e-9 |

| 25 | -0.000190336 | -2.83341e-9 |

| 30 | -0.000132315 | -2.21074e-7 |

| 35 | -0.0000972723 | -2.50754e-9 |

| 40 | -0.0000745045 | 6.09896e-6 |

| 45 | -0.0000588842 | 9.25771e-6 |

| 50 | -0.0000477058 | -0.000611088 |

| 55 | -0.0000394321 | -3.35955e-6 |

| 60 | -0.0000331376 | 7.45096e-6 |

| 65 | -0.0000282381 | 7.13059e-7 |

| 70 | -0.0000243498 | 0.000272326 |

$\rho \in(-\kappa-5,-\kappa+5)$:

| $\kappa$ | rho1kxCut | Relative Error |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | -0.0100675 | -4.05348e-9 |

| 5 | -0.00439214 | -1.14805e-11 |

| 10 | -0.0011686 | -2.57375e-10 |

| 15 | -0.000525522 | -1.60657e-11 |

| 20 | -0.00029683 | -2.65453e-11 |

| 25 | -0.000190336 | -2.58825e-10 |

| 30 | -0.000132315 | -2.18558e-7 |

| 35 | -0.0000972723 | 2.75179e-11 |

| 40 | -0.0000745045 | 6.10152e-6 |

| 45 | -0.0000588842 | 9.26034e-6 |

| 50 | -0.0000477058 | -0.000611086 |

| 55 | -0.0000394321 | -3.35706e-6 |

| 60 | -0.0000331376 | 7.45363e-6 |

| 65 | -0.0000282381 | 7.15863e-7 |

| 70 | -0.0000243498 | 0.000272329 |

For $\rho \in(\kappa-4,\kappa+4)$, the relative error is negligible. Hence we will used the cutoff version.

4.1. Summation method

At lower values of $\kappa$ we can afford finer step size, the basic Mathematica code we are gonna use is (ignore it or copy to a note book to read)

(*Set up the discretization parameters*)

\[CapitalLambda] = 50;

\[Kappa]Min = -\[CapitalLambda]; (*LargeValue should be a large \

number representing the approximation to -Infinity*)

\[Kappa]Max = \[CapitalLambda]; (*Similarly for +Infinity*)

stepSize =

0.1; (*DesiredStep is the step size for the discretization,choose \

based on desired precision*)

(*Sum up the values of rho1kx over the range using the specified step \

size*)

(*The first argument defined the range of Subscript[\[Rho], \

1Subscript[k, x]], the second argument defines the step size.*)

totalSum[\[CapitalLambda]_, stepSize_] :=

Module[{\[Kappa]Min = -\[CapitalLambda], \[Kappa]Max = \

\[CapitalLambda]},

Sum[rho1kxCut[\[Kappa]]*

stepSize, {\[Kappa], \[Kappa]Min, \[Kappa]Max, stepSize}]/(2 Pi)]

To see if summation method is stable at step size $0.01$ for various $\Lambda$, execute

Module[{data},

data = Table[

totalSum[\[CapitalLambda],

stepSize], {\[CapitalLambda], {1, 20, 1}}, {stepSize, {0.01}}];

TableForm[data,

TableHeadings -> {Table[

"\[CapitalLambda]=" <>

ToString[\[CapitalLambda]tem], {\[CapitalLambda]tem, 20}],

Table["stepSize=" <> ToString[a], {a, {0.01}}]}]

]

and we get

$\text{step size=0.01}$, $\kappa \in(-\Lambda,+\Lambda)$:

| $\Lambda$ | $2\pi\rho_ {1k_ {x}}$ |

|---|---|

| 1 | -0.046851 |

| 2 | -0.0963558 |

| 3 | -0.124661 |

| 4 | -0.14134 |

| 5 | -0.152061 |

| 6 | -0.159464 |

| 7 | -0.16486 |

| 8 | -0.168959 |

| 9 | -0.172175 |

| 10 | -0.174763 |

| 11 | -0.176889 |

| 12 | -0.178667 |

| 13 | -0.180176 |

| 14 | -0.181471 |

| 15 | -0.182596 |

| 16 | -0.183581 |

| 17 | -0.184452 |

| 18 | -0.185226 |

| 19 | -0.185919 |

| 20 | -0.186544 |

Looks stable enough.

I decided to increase the upper and lower limit $\Lambda$ until the first four or five digit (after the decimal point) stabilizes, with step size 0.01, and include the $2\pi$ factor:

(*cut_:4 means the defalut value for cut is 4, which is used unless \

an explicit value is provided for cut in the function call. rho1kxCut \

can be called as, for example, rho1kxCut[0] or rho1kxCut[0,6] *)

integrand[\[Kappa]_, \[Rho]_] := -((

9 \[Rho]^2 Csch[\[Pi] (\[Kappa] + \[Rho])]^2 (-\[Kappa]^2 + \

\[Rho]^2 + (1 + \[Kappa]^2) Log[(1 + \[Kappa]^2)/(1 + \[Rho]^2)]))/(

4 (1 + 5 \[Kappa]^2 + 4 \[Kappa]^4)));

rho1kxCut[\[Kappa]_, cut_ : 4] :=

NIntegrate[

integrand[\[Kappa], \[Rho]], {\[Rho], -\[Kappa] - cut, -\[Kappa] + cut}];

(*Set up the discretization parameters*)

\[CapitalLambda] = 50;

\[Kappa]Min = -\[CapitalLambda]; (*LargeValue should be a large \

number representing the approximation to -Infinity*)

\[Kappa]Max = \[CapitalLambda]; (*Similarly for +Infinity*)

stepSize =

0.1; (*DesiredStep is the step size for the discretization,choose \

based on desired precision*)

(*Sum up the values of rho1kx over the range using the specified step \

size*)

(*The first argument defined the range of Subscript[\[Rho], \

1Subscript[k, x]], the second argument defines the step size.*)

totalSum[\[CapitalLambda]_, stepSize_] :=

Module[{\[Kappa]Min = -\[CapitalLambda], \[Kappa]Max = \

\[CapitalLambda]},

Sum[rho1kxCut[\[Kappa]]*

stepSize, {\[Kappa], \[Kappa]Min, \[Kappa]Max, stepSize}]/(2 Pi)]

Module[{data},

data = Table[

totalSum[\[CapitalLambda],

stepSize], {\[CapitalLambda], {50, 170, 5}}, {stepSize, {0.01}}];

TableForm[data,

TableHeadings -> {Table[

"\[CapitalLambda]=" <>

ToString[\[CapitalLambda]tem], {\[CapitalLambda]tem, 20}],

Table["stepSize=" <> ToString[a], {a, {0.01}}]}]

]

We get

| $\kappa \in(-\Lambda,\Lambda)$ | stepSize=0.01 |

|---|---|

| Λ=100 | -0.0312054 |

| Λ=105 | -0.0312235 |

| Λ=110 | -0.0312399 |

| Λ=115 | -0.0312549 |

| Λ=120 | -0.0312687 |

| Λ=125 | -0.0312813 |

| Λ=130 | -0.031293 |

| Λ=135 | -0.0313038 |

| Λ=135 | -0.0313038 |

| Λ=140 | -0.0313139 |

| Λ=145 | -0.0313233 |

| Λ=150 | -0.031332 |

| Λ=155 | -0.0313402 |

| Λ=160 | -0.0313478 |

| Λ=165 | -0.031355 |

| Λ=170 | -0.0313618 |

| Λ=175 | -0.0313682 |

| Λ=180 | -0.0313742 |

| Λ=195 | -0.0313904 |

| Λ=200 | -0.0313953 |

| Λ=210 | -0.0314044 |

| Λ=220 | -0.0314126 |

| Λ=230 | -0.0314201 |

| Λ=240 | -0.031426995 |

| Λ=250 | -0.0314333 |

| Λ=300 | -0.0314587 |

| Λ=400 | -0.0314903 |

| Λ=500 | -0.0315093 |

| Λ=600 | -0.031522 |

| Λ=800 | -0.0315378 |

| Λ=1000 | -0.0315473 |

| Λ=1200 | -0.0315537 |

| Λ=1400 | -0.0315582 |

| Λ=1600 | -0.0315616 |

With step size 0.01, the first four digits after decimal point can no longer be improved by enlarging $\Lambda$.

Next, we divide the integral domain into an inner region where we use fine summations (smaller step size) and an outer region where we use coarser summation (large step size), separated by an limit $\Lambda=1600$. We do two things simultaneously, 1) increase the inner region step size from $0.005$ to $0.01$ and 2) increase the outer region step size from $0.05$ to $0.1$ until the first four or five digits after the decimal point stabilizes.

$\Lambda=1600$, Upper limit of $\kappa$ is set to be 10 000.

In the following table, large step size means 0.01 for inner region and 0.1 for outer region; small step size means 0.005 for inner region and 0.05 for outer region. Hope I had a stronger computer…

| Small Step Size (fine sum) | Large Step Size (coarse sum) | |

|---|---|---|

| Inner | -0.0315615 | -0.03156158063750391` |

| Outer | -0.000019948 | -0.0000199484 |

| Total | -0.03158147 | -0.03158153 |

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: