Kink in Quantum Field Theory, A Broad Outline

- Quantization procedure

- Introduce the particles

- Sign of the leading order correction

- Boson-fermion connection

- Equivalence of sine-Gordon and massive Thirring models

Since the details of calculation can be found in other notes, here I will only talk about the broad outline. I will use as few formula as possible.

We does it mean to quantize the kink? It is similar to what we mean by quantizing the free theory? Generally speaking, there exist two different but equivalent methods, the canonical quantization and path integral quantization. Regarding the canonical quantization,

- given a classical field theory, we first need to identify the equation of motion and its set of solutions, namely eigen functions.

- Expand the fields in these eigenfunctions, this is how we diagonalize the Hamiltonian.

- Introduce the canonical quantization relation.

In textbooks we always start from some simple model for scalar fields $\phi$, based on which the above steps are illustrated. The vacuum of the field theory is conveniently chose as $\phi=0$. In a sense, we are expanding the field in the background of $0$, namely the vacuum of the model. Then to quantize the kink simply means we change the background about which we expand the scalar field, from zero to the specific kink solution.

Using the picture of path integral things are much more obvious. Here, to consider the quantum correction to a kink solution is to include the quantum effects of fluctuation about the classical kink solution.

The quantization we described above is akin to the familiar second quantization. Further, if one would like to describe the creation and annihilation of kinks themselves by suitable kink creation and annihilation operators, this would be what people call the third quantization.

It turns out that quantum corrections always reduces the kink energy.

We will adopt perturbative methods to study the quantization of kinks. As we all know, perturbation stops working at strong coupling, $\lambda \gg 1$. What happens to $\mathcal{Z}_ {2}$ and sine-Gordon kinks when the coupling is large? From the classical kink solution we know that the mass of a kink is proportional to $1 / \lambda$, so the kink mass decreases as $\lambda$ increases. Eventually kinks will be even lighter than mesons. At large $\lambda$ we know much more in sine-Gordon model than $\mathcal{Z}_ {2}$ model. In sine-Gordon, we have a dual theory, namely the massive Thirring model.

1. Quantization procedure

The broad outline is as following.

- Consider the 2D QFT model with compact spatial dimension of size $L$. Let $\phi$ be the degree of freedom. We could adopt either periodic or anti-periodic boundary condition. Eventually we will take $L \to \infty$, but for now it is large but finite.

- Consider small quantum fluctuation $\psi$ about the kink ground $\phi_ {k}$, namely $\psi = \phi - \phi_ {k}$.

- Linearize the equation for the fluctuation field $\psi$ (not the original field). Find the solutions, also known as

eigenmodesornormal modes. Expand the fluctuation field $\psi$ in normal modes. -

Quantization.Each normal mode corresponds to a quantum harmonic oscillator, with zero point fluctuations. Sum up the zero point energies of all the normal modes. This is the quantum correction we were looking for, but without appropriate renormalization procedure the sum is divergent. -

Renormalizationmust be performed. This is the subtle part. The zero point energy of the trivial vacuum (without kink background) must be subtracted from the zero point energy of the kink, since we want the energy of the trivial vacuum to be zero. Also, the energy must be expressed in terms of renormalized parameters.

As we turn on the potential slowly, some of the low-lying modes in the trivial box become the bound states of the kink.

Notice that in the trivial vacuum, the solutions to the equation of motion, a.k.a. the scattering states, are plane waves. They are eigenfunctions to both energy and momentum operator; in the presence of a kink, however, the scattering states are now normal modes, which are eigenstates of energy operator but not eigenstates to momentum operator.

To consistently compare the energy difference between trivial vacuum sector (just vacuum sector from now on) and kink sector, we need to carefully match discrete modes (thanks to finite box size $L$) in these two.

$\mathcal{Z}_ {2}$ kink has two bound states, sine-Gordon has only one, the translational zero mode. The leading order correction to kink mass are quite close in these two cases.

2. Introduce the particles

As in the second quantization of a free quantum field theory, particle creation and annihilation operators are introduced for each of the excitation modes of the kink. This is straightforward, except for the zero mode. The final result is a quantum theory with both kinks and particles, which are sometimes referred to as mesons.

The distinctive aspect of the zero mode in second quantization is associated with its time dependence and the reality of its eigenfunction, in contrast to the complex nature of the remaining eigenfunctions. To be more specific, the time dependence of the eigenfunction is $e^{ i\omega t}$, since zero mode has zero energy, the time dependence is trivial. A real eigenfunction means that in the normal mode expansion, instead of

\[a_ {k} f _ {k} + a_ {k}^{\dagger} f_ {k}^\ast\]we have a single term, say

\[c_ {0} F,\quad F \text{ is the zero mode eigenfunction}\]and $c_ {0}^{\dagger}=c_ {0}$. It is classical since it commutes with everything (that is $c_ {0}$ itself and all the other ladder operators).

3. Sign of the leading order correction

In both $\mathcal{Z}_ {2}$ and sine-Gordon models, the leading order quantum correction reduces the energy of the kink. A argument by Coleman in his private communication show that this observation holds quite true in 1+1 dimension, with boson only. However I am not convinced by the argument. I am not gonna put the argument here, interested readers can refer to section 4.5 of Tanmay Vachaspati’s textbook.

4. Boson-fermion connection

Boson and fermion operators satisfy different (equal time) commutation relations. It is remarkable that in 1+1 dimension, it is possible to construct explicitly a fermionic operator from bosonic operators. Let $\phi$ be a scalar bosonic field and $\psi_ {1}, \psi_ {2}$ the two components of Dirac spinor (there are only two components allowed in 1D space), then

\[\psi_ {1}(x) = C : e^{ P_ {+}(x) } :_ {a}, \quad \psi_ {2} = -i C : e^{ P_ {-}(x) } :,\]The normal ordering is defined in the trivial vacuum sector, justifying us to call it a “defining” sector. $C$ is a c-number coefficient depending on mass and other cutoffs, while $P_ {\pm}$ are q-number function of $\phi(x)$.

Note that normal ordering should be treated carefully – normal ordering should be prior to commuting operators that occur within the string.

This transformation between fermionic and bosonic operators hold on the level of quantum operators, not just on the level of expectation values. Furthermore, this transformation holds independent of interactions. However, when the bosonic model is sine-Gordon model, the dual fermionic model turn out to be another well-known model – the massive Thirring model.

5. Equivalence of sine-Gordon and massive Thirring models

The sine-Gordon model is an important field theory model in both classical and quantum physics, known for its rich structure of soliton solutions. The difference between the classical and quantum versions of the sine-Gordon model, particularly in the context of ground states for various parameter values, can be understood in terms of quantization and the effects of quantum fluctuations.

The Lagrangian of sine-Gordon model is

\[L_ {sG} = \frac{1}{2} (\partial_ {\mu}\phi)^{2} - \frac{\alpha}{\beta^{2}}(1-\cos(\beta \phi)).\]where $\alpha$ is a parameter related to the amplitude of the potential, and $\beta$ controls the periodicity of the potential. The term $(1 - \cos(\beta \phi))$ represents a periodic potential with minima occurring at $\phi = 2\pi n/\beta$ for integer $n$, which are the classical ground states of the system.

The sine-Gordon model undergoes a change in behavior when quantized, particularly as the parameter $\beta$ is varied. This model does not have a well-defined ground state for

\[\beta^{2}>8\pi.\]The key to understanding the issue with having a well-defined ground state for $\beta^2 > 8\pi$ lies in the renormalization group flow of the coupling constants and the concept of quantum fluctuations.

In quantum field theory, quantum fluctuations can significantly affect the properties of a model. The coupling constants, such as the one associated with the $\beta$ parameter in the sine-Gordon model, can “run” or change their values at different energy scales due to renormalization effects. This running of the coupling constants is described by the renormalization group (RG) equations.

The condition $\beta^2 > 8\pi$ is significant because it marks a threshold beyond which the quantum fluctuations in the sine-Gordon model become so strong that they destabilize the classical vacuum structure. This can be understood in terms of the renormalization of the coupling constant $\beta$: as the energy scale changes, the effective $\beta$ can grow in such a way that the periodic potential becomes “flatter” at the quantum level, making it harder to define distinct vacuum states.

For $\beta^2 \leq 8\pi$, the renormalization effects are such that the theory can maintain its integrability and the solitons (or topological excitations) of the sine-Gordon model have well-defined, finite masses. These solitons can be thought of as the “particles” of the quantum field theory, and their stability is crucial for the theory to have a well-defined ground state.

When $\beta^2 > 8\pi$, the quantum corrections make the mass of these solitons diverge, leading to a loss of particle-like excitations that could stabilize the ground state. This destabilization is related to the fact that the quantum theory no longer supports stable soliton solutions as it does in the classical case or in the quantum case for smaller $\beta$. The vacuum structure becomes ambiguous due to the proliferation of vacuum fluctuations, making it challenging to define a unique ground state. As a result, for $\beta^2 > 8\pi$, the sine-Gordon model does not have a well-defined ground state due to the strong quantum fluctuations that destabilize the classical vacuum structure.

In the range $0 < \beta^{2} < 8\pi$, the sine-Gordon model is dual to massive Thirring model whose Lagrangian reads

\[\mathcal{L}_ {mT} = i\overline{\psi} \partial\llap{/}\, \overline{\psi} - m \overline{\psi} \psi - \frac{g}{2} j^{\mu} j_ {\mu},\quad j^{\mu} := \overline{\psi} \partial^{\mu}\psi.\]The relations between coupling is

\[\frac{g}{\pi} = 1- \frac{4\pi}{\beta^{2}}.\]The fermionic field $\psi$ creates a fermion after quantization, it also creates a kink in terms of $\phi$ field. Hence the sine-Gordon kink is identified with the fermion in the massive Thirring model. The fermion in the massive Thirring model carries a topological charge in the sine-Gordon model.

The massive Thirring model does not have soliton solutions (a solution for a Dirac field represents a state that a fermion can occupy, not a classical soliton or anything like that), however fermions can form bound states, for the interaction between a fermion and an anti-fermion is attractive. It can be shown that such a bound state corresponds to a scalar field created by $\phi$.

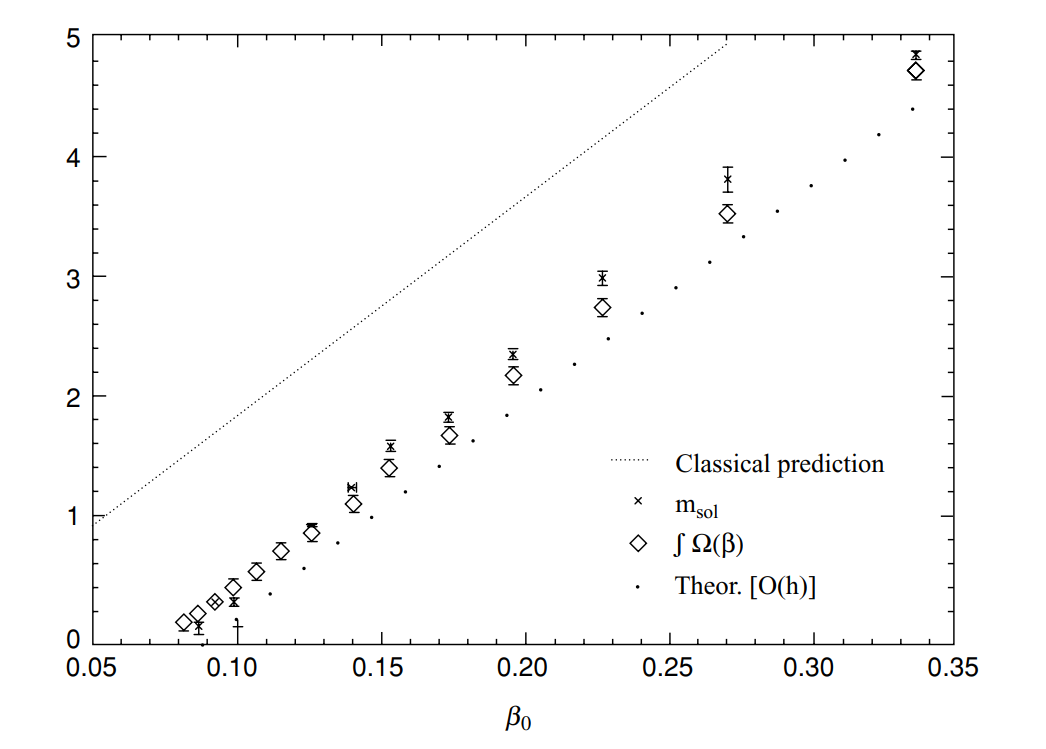

We have a few options for the fundamental degree of freedom, including the boson $\phi$, the fermions $\psi$, the kink of $\phi$, the bound state of $\psi$. Which one is the fundamental dof depends on its mass. For example, in the massive Thirring model let mass of a single fermion be $m$, a pair of fermion-antifermion has mass less than $2m$ due to the interaction between them. As the coupling increases, the interaction strengthens and the mass further reduces. Eventually the bounded pair will be lighter than a single fermion, then the bound state should be regarded as the fundamental degree of freedom. We know that the bounded state corresponds to boson created by $\phi$ field, hence the fundamental description should be the sine-Gordon model. A dual picture exists for $\phi$ and kink, a lattice result is shown in the below.

The construction of fermion operators from boson operator and vise versa has been used extensively in condensed matter physics under the name of bosonization.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: