Regression Methods in Biostatistics

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Basic Statistical Methods

- 3. Correlation

- 4. Linear Regression Method

- 5. Logistic Regression method

- 6. Entropy in Statistics

1. Introduction

In life some questions are too important to be left to opinion, superstition, or conjecture. For example, which drug should a doctor prescribe to treat an illness? What factors increase the risk of an individual developing coronary heart attack? To answer these questions (even remotely), we need objective, evidence-based decision making method.

Evidence-based practice: Using sound research findings based on observed or collected data to make decisions.

In principle, people collect and process information every day of their lives. Since it’s something we do frequently, you might think we would be really good at it…but we’re not. We are not good at picking out patterns from a sea of noisy data. And, on the flip side, we are too good at picking out non-existent patterns from small numbers of observations.

In order to mitigate any of our own personal biases when answering important questions about the way the world works (i.e., to do good science), we must be careful to be rigorous in the way we proceed. The scientific method is the process used to answer scientific questions.

- Ask the question

- Construct a hypothesis

- Test it with a study or an experiment

- Analyze data and draw conclusions (wish its as simple as that)

- Communicate results

However, collecting and analyzing data can be complicated. Statistics helps us design studies, test hypotheses, and use data to make scientifically valid conclusions about the world. In general, scientists use the scientific method to make generalizations about classes of people on the basis of their studies. The class of people that they are trying to make generalizations about is called the population. Most of the time, it is impractical and expensive to study all individuals in a population, Instead of sampling everyone in the population, or taking a census, typically we study only a portion of the population called the sample. In order to determine how best to obtain a sample to answer the research questions, we must be cautious about the study design. Then, researchers make generalizations, or inference, about the entire population based on studying the sample.

In this note we consider two broad categories of statistical analysis: descriptive statistics, which deals with methods for summarizing and/or presenting data and inferential statistics.

Descriptive statistics: Methods for summarizing and/or presenting data. Inferential statistics: Methods for making generalizations about a population using information contained in the sample.

It is difficult to sort through large streams of data and make any meaningful conclusions. Instead, we can better understand data by condensing it into human readable mediums through the use of data summaries, often displayed in the forms of tables and figures. However, in doing so, information is often be lost in the process. A good data summary will seek to strike a balance between clarity and completeness of information.

There are two broad types of data that we may see in the wild, which we will call categorical data and continuous data. As the name suggests, categorical data (sometimes called qualitative or discrete data) are data that fall into distinct categories. Categorical data can further be classified into two distinct types:

- Nominal data: data that exists without any sort of natural or apparent ordering, e.g., colors (red, green, blue), gender (male, female), and type of motor vehicle (car, truck, SUV).

- Ordinal data: data that does have a natural ordering, e.g., education (high school, some college, college) and injury severity (low, medium, high).

Continuous data (sometimes called quantitative data), on the other hand, are data that can take on any numeric value on some interval or on a continuum. Examples of continuous data include height, weight, and temperature. Categorical and continuous data are summarized differently, and we’ll explore a number of ways to summarize both types of data.

Below are some terminologies.

Absolute frequency: The number of observations in a category Rate/Relative frequency: The number of observations in a category relative to any other quantity Percent/Proportion: The number of observations per 100 Bar plot: Visualization of categorical data which uses bars to represent each category, with counts or percents represented by the height of each bar Stratification: The process of partitioning data into categories prior to summarizing

The two most common ways to describe the center are with the mean and the median. We all know what the mean is. The median is another common measure of the center of a distribution. In particular, for a set of observations, the median is an observed value that is both larger than half of the observations, as well as smaller than half of the observations.

Sometimes there lies some data that are extremely different than the rest. Take the salaries of staff of some American university, the highest paid employee is usually the football coach, and much much higher then the rest. This one high salary, which is not representative of most of the salaries collected, is known as an outlier. In this particular case, the mean is highly sensitive to the presence of outliers while the median is not. Measures that are less sensitive to outliers are called robust measures. The median is a robust estimator of the center of the data.

The shape of a distribution is often characterized by its modality and its skew. The modality of a distribution is a statement about its modes, or “peaks.” Distributions with a single peak are called unimodal, whereas distributions with two peaks are call bimodal. Multimodal distributions are those with three or more peaks. The skew on the other hand describes how our data relates to those peaks. Distributions in which the data is dispersed evenly on either side of a peak are called symmetric distributions; otherwise, the distribution is considered skewed. The direction of the skew is towards the side in which the tail is longest.

In addition to measuring the center of the distribution, we are also interested in the spread or dispersion of the data. Two distributions could have the same mean or median without necessarily having the same shape. Perhaps the most intuitive methods of describing the dispersion of our data are those associated with percentile-based summaries. Formally, the $p$-th percentile is some value $V_ {p}$ such that

- $p\%$ of observations are $\leq V_ {p}$;

- $1-p\%$ of observations are $\gg V_ {p}$.

The quartile is made of

A commonly used percentile-based measure of spread combining these measures is the interquartile range (IQR), defined as

\[\text{IQR} := Q_ {3} - Q_ {1}.\]The IQR is not impacted by the presence of outliers, so it is considered a robust measure of the spread of the data. So, like the median, it enjoys the quality of being a robust measure of the data.

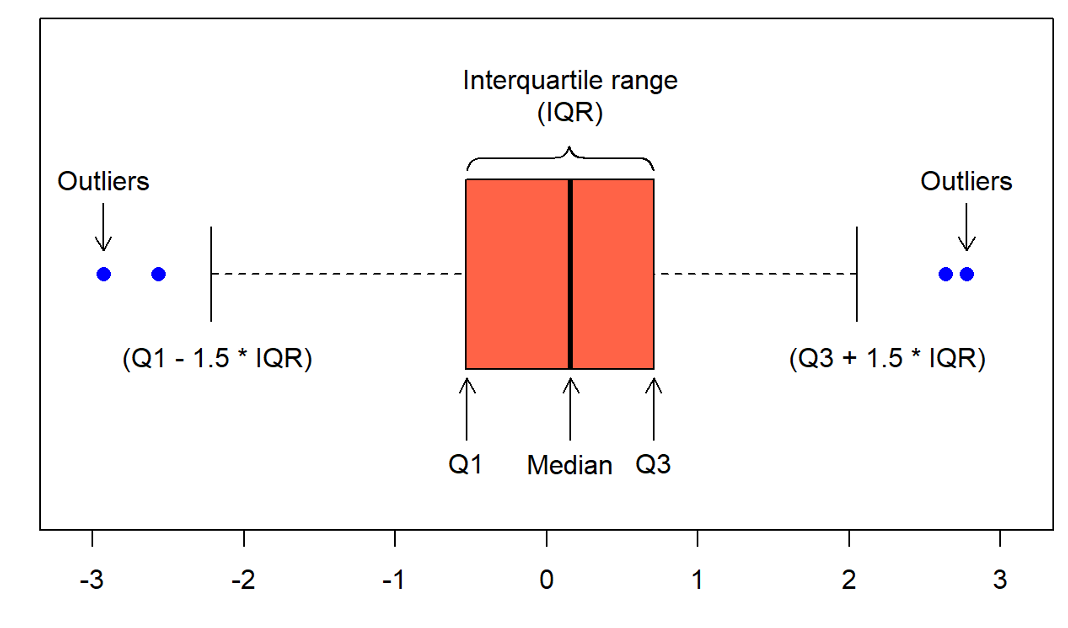

Percentiles are also used to create another common visual representation of continuous data: the boxplot, also known as a box-and-whisker plot. A boxplot consist of the following elements:

- A box, indicating the Interquartile Range (IQR), bounded by the values $Q_ {1}$ and $Q_ {3}$;

- The median, or $Q_ {2}$, represented by the line drawn within the box;

- The “whiskers,” extending out of the box, which can be defined in a number of ways. Commonly, the whiskers are 1.5 times the length of the IQR from either $Q_ {1}$ or $Q_ {3}$;

- Outliers, presented as small circles or dots, and are values in the data that are not present within the bounds set by either the box or whiskers.

The variance and the standard deviation are numerical summaries which quantify how spread out the distribution is around its mean.

We have two kinds of variances: sample variance and population variance. The difference between sample variance and population variance lies in how they are calculated and what they represent in the context of statistical analysis.

Population Variance:

Population variance measures how much the members of a population differ from the population mean. It is denoted by $\sigma^2$. If you have a population with $N$ members and population values $x_ 1, x_ 2, …, x_ N$, the population variance $\sigma^2$ is calculated as:

\[\sigma^2 = \frac{1}{N} \sum_ {i=1}^{N} (x_ i - \mu)^2\]where $\mu$ is the population mean. Note that $\mu$ is not the mean of some measured data, it is supposed to be given by some theoretical model. Population variance is used when you have access to all the data points in the population.

Sample Variance

Sample variance measures how much the members of a sample (a subset of the population) differ from the sample mean. It is an estimator of the population variance. Sample variance is denoted by $s^2$. If you have a sample of size $n$ with values $x_ 1, x_ 2, …, x_ n$, the sample variance $s^2$ is calculated as:

\[s^2 = \frac{1}{n-1} \sum_ {i=1}^{n} (x_ i - \overline{x})^2\]where $\overline{x}$ is the sample mean.

Key Differences:

- Purpose: Population variance describes the variability within an entire population, while sample variance estimates the population variance from a subset of the population.

- Formula: The population variance formula divides by $n$ (the total number of population members), whereas the sample variance formula divides by $n-1$ (one less than the sample size).

- Bias Correction: The use of $n-1$ in the sample variance formula, known as Bessel’s correction, corrects for the bias in the estimation of population variance from a sample.

When we calculate the variance of a sample, we typically use the sample mean $\overline{x}$ as an estimate of the true population mean. However, using the sample mean introduces a bias because it is based on the same data points that we are using to calculate the variance. This means the sum of the squared deviations $(x_ i - \overline{x})^2$ tends to be smaller than it would be if we used the true population mean, leading to an underestimate of the true population variance.

To correct for this bias, we use $n-1$ in the denominator instead of $n$. This adjustment is known as Bessel’s correction. The rationale behind it is that when estimating variance from a sample, we lose one degree of freedom because we have estimated the mean from the same data set. Using $n-1$ effectively compensates for this loss, making the sample variance an unbiased estimator of the true population variance.

In summary, the factor $\frac{1}{n-1}$ is used instead of $\frac{1}{n}$ to make the sample variance an unbiased estimator of the population variance, accounting for the fact that the sample mean is used in the variance calculation.

The standard deviation, denoted as $s$, is a function of variance. Recall that the mean is not a robust outlier and is highly sensitive to skew or the presence of outliers. Consequently, the variance and the standard deviation are also very sensitive.

The regression method is a statistical technique used to model and analyze the relationships between a dependent variable and one or more independent variables. The primary goal of regression is to predict the value of the dependent (or response) variable based on the values of the independent (or predictor) variables. It is widely used in various fields such as economics, finance, biological sciences, and social sciences for forecasting, estimating, and determining causal relationships.

There are several types of regression methods, each suited to different types of data and relationships:

-

Linear Regression: The simplest form of regression, linear regression uses a linear approach to model the relationship between the dependent variable and one or more independent variables. The model assumes that the relationship can be described by a straight line in the form $y = \beta_ 0 + \beta_ 1x_ 1 + \epsilon$, where $y$ is the dependent variable, $x_ 1$ is the independent variable, $\beta_ 0$ is the y-intercept, $\beta_ 1$ is the slope of the line, and $\epsilon$ represents the error term.

-

Multiple Linear Regression: An extension of simple linear regression, this method involves two or more independent variables. The model is expressed as $y = \beta_ 0 + \beta_ 1x_ 1 + \beta_ 2x_ 2 + … + \beta_ nx_ n + \epsilon$, where $x_ 1, x_ 2, …, x_ n$ are the independent variables.

-

Logistic Regression: Used when the dependent variable is categorical, typically binary. Logistic regression models the probability that the dependent variable belongs to a particular category, using a logistic function.

-

Polynomial Regression: A form of regression where the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable is modeled as an nth degree polynomial. Polynomial regression fits a nonlinear relationship between the value of x and the corresponding conditional mean of y.

-

Ridge and Lasso Regression: These are types of linear regression that include regularization. Regularization adds a penalty on the size of coefficients to prevent overfitting. Ridge regression adds a squared magnitude of the coefficient as a penalty term to the loss function, while Lasso regression adds the absolute value of the magnitude of the coefficient as a penalty term.

-

Non-linear Regression: Used when the data cannot be modeled using linear methods due to a non-linear relationship between the dependent and independent variables. Non-linear regression can fit complex curves to data.

Regression analysis involves selecting the appropriate model for the data, estimating the model parameters (usually through methods like least squares), evaluating the model’s adequacy (checking for goodness-of-fit, residuals, etc.), and interpreting the results to make inferences or predictions.

In practice, the choice of regression method depends on the nature of the dependent variable, the shape of the relationship, and the distribution of the residuals, among other factors. Proper model selection, diagnostic testing, and validation are crucial steps in ensuring that the regression model provides reliable and accurate predictions or insights.

2. Basic Statistical Methods

2.1. t-Test and ANOVA (Analysis of Variance)

My time is really limited here so I’ll direct jump to a short review of some mostly commonly used statistical methods.

The basic $t$-test is used to compare two independent samples. The t-statistic on which the test is based is the difference between the two sample averages, divided by the standard error of that difference. The t-test is designed to work in small samples, whereas Z-tests are not.

2.1.1. t-test

Below is the gist of the derivation of the t-distribution. Assume we have a population that follows a normal distribution with mean $\mu$ and standard deviation $\sigma$. We take a random sample of size $n$ from this population, and we calculate the sample mean $\bar{x}$. The sample mean $\bar{x}$ is also normally distributed (due to the Central Limit Theorem) with mean $\mu$ and standard deviation $\sigma / \sqrt{n}$. We standardize $\bar{x}$ to transform it into a standard normal variable $Z$:

\[Z = \frac{\bar{x} - \mu}{\sigma / \sqrt{n}}\]In practice, $\sigma$ (the population standard deviation) is often unknown and must be estimated from the sample. We use the sample standard deviation $s$ as an estimate for $\sigma$, where $s$ is calculated from the sample data. We replace $\sigma$ with $s$ in the standardization formula, but this introduces additional variability because $s$ is an estimate:

\[T = \frac{\bar{x} - \mu}{s / \sqrt{n}}\]This ratio $T$ does not follow a standard normal distribution anymore due to the uncertainty introduced by using $s$ instead of $\sigma$. Instead, the variable $T$ follows a distribution that is similar to the normal distribution but with heavier tails. This is the t-distribution. The exact shape of the t-distribution depends on the sample size $n$ through the degrees of freedom, which is $n - 1$ in this context. The degrees of freedom account for the additional uncertainty introduced by estimating the population standard deviation.

The t-distribution is formally defined through its probability density function (pdf), which is more complex than that of the normal distribution and involves the Gamma function. The pdf of the t-distribution for a given $t$ value and $v$ degrees of freedom (where $v = n - 1$) is given by:

\[f(t; v) = \frac{\Gamma((v+1)/2)}{\sqrt{v\pi}\Gamma(v/2)} \left(1 + \frac{t^2}{v} \right)^{-(v+1)/2}\]where $\Gamma$ is the Gamma function, a generalization of the factorial function to complex numbers.

In short, remember the following:

- The t-distribution accounts for the additional uncertainty in estimating the population mean when the population standard deviation is unknown and the sample size is small.

- As the sample size increases, the t-distribution approaches the standard normal distribution because the estimate $s$ becomes more accurate, reducing the extra uncertainty.

In the context of the t-test and statistical hypothesis testing, “significance” refers to the degree to which the test results allow us to reject the null hypothesis. The null hypothesis typically proposes that there is no effect or no difference between groups or conditions. When we say a result is “statistically significant,” it means that the observed data are unlikely to have occurred under the null hypothesis, suggesting that there is a real effect or difference.

The significance level, denoted as $\alpha$, is a threshold set by the researcher before conducting the test, which defines the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis when it is actually true (a type I error). Common values for $\alpha$ are 0.05, 0.01, and 0.10, with 0.05 being the most widely used. Setting $\alpha$ at 0.05 means that there is a 5% risk of concluding that a difference exists when there is no actual difference.

The p-value is a key metric derived from the t-test that indicates the probability of observing the test results, or more extreme results, if the null hypothesis were true. A p-value that is less than or equal to the significance level ($p \leq \alpha$) indicates that the observed data are unlikely under the null hypothesis, leading to the rejection of the null hypothesis. In simpler terms, a low p-value (typically ≤ 0.05) suggests that the evidence against the null hypothesis is strong enough to consider the results statistically significant.

Interpretation of Significance

-

Statistically Significant: If the test result is statistically significant, it suggests that the evidence is strong enough to reject the null hypothesis. This typically means there is a meaningful difference between the groups being compared, which is not likely to have occurred by chance.

-

Not Statistically Significant: If the result is not statistically significant, it suggests that the evidence is not strong enough to reject the null hypothesis. This could mean that there is no meaningful difference between the groups, or that the study did not have enough power (e.g., sample size was too small) to detect a difference if one exists.

It’s important to note that statistical significance does not necessarily imply practical or clinical significance. A result can be statistically significant but still be of little practical value if the observed effect or difference is too small to be of interest or use in a practical context.

2.1.2. Two-sided Hypothesis Test

In biostatistics, the two-sided t-test (also known as the two-tailed t-test) is commonly used to determine whether there is a significant difference between the means of two groups, without specifying the direction of the difference. This type of test is employed when the research question is concerned with whether there is any difference at all, rather than predicting which group will have a higher or lower mean.

Biostatistics often involves comparing biological measurements or outcomes across different groups. For instance, one might compare the efficacy of two different medications, the impact of a treatment versus a placebo, or physiological measurements (like blood pressure) between two groups with different dietary habits. In these cases, researchers might not have a strong hypothesis about which group will have higher or lower means, or they may wish to test for the possibility of a difference in either direction. The two-sided t-test is ideal for these scenarios because it allows for the detection of significant differences regardless of their direction.

The formula for the t-statistic in a two-sided t-test is similar to that of a one-sided t-test, but the interpretation of the p-value and the critical value from the t-distribution is different.

For an independent two-sample t-test, the formula for the t-statistic remains:

\[t = \frac{\bar{x}_ 1 - \bar{x}_ 2}{\sqrt{s^2 \left(\frac{1}{n_ 1} + \frac{1}{n_ 2}\right)}}\]However, in a two-sided t-test, you’re interested in differences in both directions, so you consider both tails of the distribution when determining the critical t-value or when interpreting the p-value.

The hypotheses for a two-sided t-test are formulated as follows:

- Null Hypothesis ($H_ 0$): There is no difference between the group means ($\mu_ 1 = \mu_ 2$).

- Alternative Hypothesis ($H_ a$): There is a difference between the group means ($\mu_ 1 \neq \mu_ 2$).

In a two-sided t-test, the p-value represents the probability of observing a test statistic as extreme as, or more extreme than, the one observed, in either direction, assuming the null hypothesis is true. If this p-value is less than or equal to the chosen significance level ($\alpha$), the null hypothesis is rejected, indicating a statistically significant difference between the two group means.

A significant result in a two-sided t-test suggests that there is enough evidence to conclude that a difference exists between the two group means, but it does not indicate which group has the higher mean. This approach is particularly useful in biostatistics, where establishing the existence of a difference can be crucial for further research, clinical decisions, or policy-making, even before the direction of the difference is fully understood.

2.1.3. F-test

Suppose that we need to compare sample averages across the arms of a clinical trial with multiple treatments, or more generally across more than two independent samples. For this purpose, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the F-test take the place of the t-test. F-test technique extends the t-test, which compares only two means, by allowing comparisons among multiple groups simultaneously, thus providing a holistic view of the data.

In the context of $F$-test, the null hypothesis is that the mean values of the outcomes from all the populations sampled from are the same, against the alternative that the means differ in at least two of the samples.

The F-test is based on the F-distribution and uses an F-statistic to test the null hypothesis. The test essentially compares the variance between the groups to the variance within the groups; a higher ratio suggests that the group means differ significantly.

Key Concepts of One-Way ANOVA are

-

Between-Group Variability: Differences among the group means, which reflect the effect of the independent variable. -

Within-Group Variability: Variations within each group, attributed to random error or individual differences not due to the treatment effect. -

F-Statistic: A ratio of the between-group variability to the within-group variability. A larger F-statistic indicates a greater likelihood that significant differences exist among the group means.

F-test assumes that:

- Independence of Observations: The data in different groups should be independent of each other.

- Normality: The distribution of the residuals (errors) should be approximately normally distributed for each group.

- Homogeneity of Variances: The variances among the groups should be approximately equal.

Next we will give the gist of the derivation of F-distribution, follow by an example of application.

Roughly speaking, the F-distribution arises when dividing one $\chi^{2}$ (chi-square) distributed variable by another, each divided by their respective degrees of freedom. Here’s a step-by-step explanation:

Consider two independent chi-square distributed variables, $X$ and $Y$, with degrees of freedom $d_ 1$ and $d_ 2$, respectively. These chi-square variables can be thought of as the sum of squares of $d_ 1$ and $d_ 2$ independent standard normal variables.

The probability density functions (pdf) for $X$ and $Y$ are given by:

\[f_ X(x) = \frac{1}{2^{d_ 1/2}\Gamma(d_ 1/2)} x^{d_ 1/2 - 1} e^{-x/2}, \quad x > 0\] \[f_ Y(y) = \frac{1}{2^{d_ 2/2}\Gamma(d_ 2/2)} y^{d_ 2/2 - 1} e^{-y/2}, \quad y > 0\]where $\Gamma$ denotes the Gamma function.

The F-statistic is constructed by dividing $X/d_ 1$ by $Y/d_ 2$, each chi-square variable divided by its degrees of freedom, which normalizes them:

\[F = \frac{X/d_ 1}{Y/d_ 2}\]To derive the pdf of the F-distribution, we need to find the distribution of the variable $F$. This involves some complex integration because we have to consider the joint distribution of $X$ and $Y$, and then transform it to the distribution of $F$. The transformation involves the Jacobian of the transformation from $(X, Y)$ to $(F, Y)$, and then integrating out $Y$ to get the marginal distribution of $F$. After performing the necessary mathematical manipulations, the pdf of the F-distribution for a given $f$ value, with degrees of freedom $d_ 1$ and $d_ 2$, is given by:

\[f(f; d_ 1, d_ 2) = \frac{\Gamma((d_ 1+d_ 2)/2)}{\Gamma(d_ 1/2)\Gamma(d_ 2/2)} \left(\frac{d_ 1}{d_ 2}\right)^{d_ 1/2} f^{d_ 1/2 - 1} \left(1 + \frac{d_ 1}{d_ 2}f\right)^{-(d_ 1+d_ 2)/2}, \quad f > 0\]This distribution is used to test hypotheses about the equality of variances of two normally distributed populations, among other applications.

Next, an example:

Imagine a researcher wants to investigate the effect of different teaching methods on student performance. The researcher divides a group of 90 students into three equal groups, each subjected to a different teaching method: Method A (traditional), Method B (interactive), and Method C (technology-assisted). After a semester, the researcher measures the performance of each student on a standardized test.

The research question is: “Do the three teaching methods result in different student performance levels?”

To address this question using one-way ANOVA, the researcher would:

- Calculate the group means: Find the average performance score for students in each teaching method group.

- Compute the ANOVA statistics: Determine the between-group and within-group variances and calculate the F-statistic.

- Compare the F-statistic to a critical value from the F-distribution: The critical value depends on the level of significance (usually set at 0.05) and the degrees of freedom for the numerator (between-groups, $k - 1$, where $k$ is the number of groups) and the denominator (within-groups, $N - k$, where $N$ is the total number of observations).

If the computed F-statistic is greater than the critical value, the null hypothesis is rejected, suggesting that there is a significant difference in student performance across at least two of the teaching methods. The researcher might then conduct post-hoc tests to identify specifically which groups differ from each other.

2.1.4. Robustness

We have assumed normal distribution for the distribution of random variables. However, both the t-test and the F-test are pretty robust to violations of the normality assumption, especially in large samples, similar to the central limit theorem. By robust we mean that the type-I error rate, which is the mistake of rejecting the null hypothesis when it actually holds, is not seriously affected. They are, however, primarily sensitive to outliers, which will mess up the variation.

Specifically for the independent two-sample t-test, there’s an important assumption known as the equal variance assumption or homoscedasticity. This assumption states that the variance within each of the groups being compared should be approximately equal. The t-test is less robust to violations to this assumption, which can seriously affect the type-I error rate (and not always in conservative direction). In contrast, the overall F-test in ANOVA loses efficiency, but the error rate of type-I is use seriously increases. If the assumption of equal variances is violated, adjustments to the t-test can be made to account for the difference in variances. One common approach is to use Welch’s t-test, which does not assume equal population variances. Welch’s t-test adjusts the degrees of freedom of the t-test based on the sample sizes and variances of the two groups, making it more reliable when the variances are unequal.

3. Correlation

Pearson correlation coefficient, often symbolized as $r$, is a measure of the linear correlation between two variables $X$ and $Y$. In biostatistics, it’s widely used to quantify the degree to which two biological or health-related variables are linearly related. The value of $r$ ranges from -1 to +1, where:

- $r = 1$ indicates a perfect positive linear relationship,

- $r = -1$ indicates a perfect negative linear relationship,

- $r = 0$ suggests no linear relationship.

In biostatistics, Pearson correlation is used to explore relationships between various biological, clinical, or health-related variables. Some examples include:

-

Gene Expression Studies: Researchers might use Pearson correlation to assess the relationship between the expression levels of two genes across various conditions or tissue types, helping to identify potentially co-regulated genes or gene pairs with opposing expression patterns.

-

Nutritional Epidemiology: It can be used to explore the relationship between dietary intake (like calorie intake) and health outcomes such as blood pressure or cholesterol levels. A positive correlation might suggest that higher intake is associated with higher blood pressure, while a negative correlation could indicate the opposite.

-

Clinical Trials: In trials, Pearson correlation might be applied to examine the relationship between the dose of a drug and its effect on a biomarker. A positive correlation would suggest that as the dose increases, the biomarker levels also increase, indicating a possible dose-response relationship.

The Pearson correlation coefficient is calculated as:

\[r = \frac{\left\langle (x-\overline{x})(y-\overline{y}) \right\rangle }{\sqrt{ \left\langle (x-\overline{x})^{2} \right\rangle \left\langle (y-\overline{y})^{2} \right\rangle }}\]Where $\left\langle \bullet \right\rangle$ is the sample mean of $\bullet$, not the population mean.

While the Pearson correlation coefficient is a powerful tool, it has limitations. It only measures linear relationships, so it may not capture more complex patterns. Additionally, it is sensitive to outliers, which can disproportionately affect the correlation coefficient. Finally, a significant Pearson correlation does not imply causation; it only indicates that a linear relationship exists.

Like the $t$-test and linear regression, the correlation coefficients are sensitive to outliers. In this case, a robust alternative is the Spearman correlation coefficient, which is equivalent to the Pearson coefficient applied to the ranks of $x$ and $y$. By rank we mean position in the ordered sequence of the values of a variable. For example, if $x$ takes on values $1.2,5.1,4.3,16.0$, then we first order them from small to large, then the so-called rank is the position; the rank of $1.2$ is 1, the rank of 4.3 is 2, the rank of the outlier 16.0 is 4. In the given order the outliers are by construction either on the smallest end or the largest end. Ranks are used in a range of nonparametric methods, in no small part because of their robustness when the data include outliers. Their disadvantage is that any information contained in the measured values of the outcome beyond the ranks is lost.

To be more specific, here’s a step-by-step explanation of how ranking is done, along with an example:

-

Sort the data: Arrange the data in ascending or descending order.

-

Assign ranks: Assign ranks to each observation based on its position in the sorted data. The smallest observation gets a rank of 1, the second smallest gets a rank of 2, and so on.

-

Handle tied ranks: If there are tied values (i.e., two or more observations with the same value), assign them the average of the ranks they would have received. For example, if two observations tie for the second smallest value, each would receive a rank of 2.5.

Let’s illustrate this with an example. Consider the following dataset: 10, 15, 8, 20, 25, 15, 30

-

Sort the data: 8, 10, 15, 15, 20, 25, 30

-

Assign ranks:

- 8 gets a rank of 1

- 10 gets a rank of 2

- 15 gets a rank of 3.5 (average of ranks 3 and 4)

- 15 gets a rank of 3.5 (average of ranks 3 and 4)

- 20 gets a rank of 5

- 25 gets a rank of 6

- 30 gets a rank of 7

Kendall’s tau (often denoted as $\tau$) is a measure of association or correlation between two ranked variables. It’s a non-parametric statistic, meaning it doesn’t assume any specific distribution for the variables involved. Kendall’s tau is particularly useful when dealing with ranked or ordinal data, where the exact numerical values of the data points might not be as important as their relative ordering.

The formula for Kendall’s tau for two variables $X$ and $Y$ with $n$ observations each is given by:

\[\tau = \frac{\text{Number of concordant pairs} - \text{Number of discordant pairs}}{\text{Number of possible pairs}}\]Where:

- A pair of observations $X_ i, Y_ i$ and $X_ j, Y_ j$ is considered concordant if the ranks agree, i.e., if $(X_ i - X_ j)(Y_ i - Y_ j) > 0$.

- A pair is discordant if the ranks disagree, i.e., if $(X_ i - X_ j)(Y_ i - Y_ j) < 0$.

- The number of possible pairs is the total number of pairs of observations, which is $\frac{n(n-1)}{2}$ for n observations.

Let’s go through an example to illustrate Kendall’s tau:

Suppose we have the following ranked data for two variables X and Y:

\(X: 5, 3, 1, 4, 2\) \(Y: 2, 4, 5, 1, 3\)

Step 1: Calculate the number of concordant and discordant pairs.

- Concordant pairs: Count the pairs where the ranks agree.

- Discordant pairs: Count the pairs where the ranks disagree.

pairs (5, 4), (5, 3), (4, 2), (3, 2)

\[\text{Discordant pairs} = 6\]pairs (5, 2), (5, 1), (5, 3), (4, 1), (4, 3), (3, 1)

Step 2: Calculate Kendall’s tau.

\[\tau = \frac{\text{Concordant pairs} - \text{Discordant pairs}}{\text{Number of possible pairs}}\] \[\tau = \frac{4 - 6}{\frac{ {5(5-1)}}{2} } = \frac{-2}{10} = -0.2\]So, Kendall’s tau for the given data is -0.2.

Interpretation: Since Kendall’s tau is negative, it suggests a slight negative association between variables X and Y. This means that as the rank of X increases, the rank of Y tends to decrease slightly, and vice versa.

Kendall’s tau is widely used in various fields, especially when dealing with ranked or ordinal data, as it provides a robust measure of association that is not sensitive to the specific values of the ranks.

4. Linear Regression Method

Linear regression methods in biostatistics are used to describe the relationship between one or more independent (predictor or explanatory) variables and a continuous dependent (outcome) variable. These methods are fundamental in biostatistical analysis for understanding associations, predicting outcomes, and identifying potential causal relationships in health sciences. The primary methods include:

- Simple Linear Regression:

- Description: Examines the relationship between a single independent variable (X) and a dependent variable (Y).

- Model: The relationship is modeled as $Y = \beta_ 0 + \beta_ 1X + \epsilon$, where $\beta_ 0$ is the y-intercept, $\beta_ 1$ is the slope of the line (indicating the change in Y for a one-unit change in X), and $\epsilon$ represents the error term.

- Use Cases: Used when you want to see how changes in one predictor variable influence changes in the outcome. For example, studying the effect of drug dosage on blood pressure levels.

- Multiple Linear Regression (MLR):

- Description: Extends simple linear regression to include multiple independent variables.

- Model: $Y = \beta_ 0 + \beta_ 1X_ 1 + \beta_ 2X_ 2 + … + \beta_ kX_ k + \epsilon$, where $\beta_ 0$ is the intercept, $\beta_ i$ are the coefficients for each predictor $X_ i$, and $\epsilon$ is the error term.

- Use Cases: Useful when investigating the impact of several factors on an outcome. For instance, assessing how patient age, weight, and smoking status together influence the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases.

- Polynomial Regression:

- Description: A form of regression analysis where the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable is modeled as an nth degree polynomial.

- Model: $Y = \beta_ 0 + \beta_ 1X + \beta_ 2X^2 + … + \beta_ nX^n + \epsilon$.

- Use Cases: Employed when the relationship between variables is not linear, allowing for a better fit to data that display curvature. For example, modeling the growth rate of bacteria at different temperatures might require a polynomial fit.

- Ridge Regression (L2 Regularization):

- Description: Addresses multicollinearity (high correlation among independent variables) in MLR by adding a penalty term equal to the square of the magnitude of the coefficients.

- Model: The cost function is $\text{Cost} = \left\lVert Y - X\beta \right\rVert ^2 + \lambda \left\lVert \beta \right\rVert ^2$, where $\lambda$ is the penalty term.

- Use Cases: Useful in situations with many predictors, some of which might be correlated. It helps in reducing overfitting by shrinking the coefficients.

- Lasso Regression (L1 Regularization):

- Description: Similar to ridge regression but uses an absolute value penalty for the size of coefficients, which can lead to some coefficients being exactly zero.

- Model: The cost function is $\text{Cost} = \left\lVert Y - X\beta \right\rVert ^2 + \lambda \left\lVert \beta \right\rVert$.

- Use Cases: Used for variable selection and regularization to improve prediction accuracy and interpretability of the statistical model by excluding irrelevant variables.

- Elastic Net Regression:

- Description: Combines penalties of ridge regression and lasso regression.

- Model: The cost function includes both L1 and L2 penalties, $\text{Cost} = \lVert Y - X\beta\rVert ^2 + \lambda_ 1 \lvert\beta\rvert + \lambda_ 2 \lVert\beta\rVert^2$.

- Use Cases: Effective when there are multiple correlated variables, providing a balance between ridge and lasso regression by including both sets of penalties.

Some comments. Ridge Regression is called L2 regularization because of the nature of the penalty applied to the coefficients in the regression model. In this context, “L2” refers to the L2 norm of the coefficient vector, which is used as the penalty term. The L2 norm is essentially the square root of the sum of the squared vector values, but in the context of ridge regression, the penalty term involves the square of the L2 norm (i.e., the sum of the squared values of the coefficients, not taking the square root).

More mathematically, for a regression coefficient vector $\beta = [\beta_ 1, \beta_ 2, …, \beta_ n]$, the L2 norm is defined as:

\[\lVert\beta\rVert_ 2 = \sqrt{\beta_ 1^2 + \beta_ 2^2 + ... + \beta_ n^2}\]In ridge regression, the penalty term added to the cost function (which is minimized during the training of the model) is the square of this L2 norm (hence the term “L2 regularization”), but it’s often just presented without the square root to begin with in the context of ridge regression.

The rationale behind using L2 regularization (ridge regression) is to prevent overfitting by shrinking the coefficients of less important features towards zero (though not exactly zero, which is a characteristic of Lasso regression, or L1 regularization). This is particularly useful when dealing with multicollinearity or when the number of predictor variables is large relative to the number of observations. The L2 regularization term penalizes large coefficients, thus enforcing a constraint on the size of coefficients, which can lead to more robust and better-generalized models.

Overfitting occurs when a statistical model or machine learning algorithm captures the noise of the data rather than the underlying pattern. It happens when the model is too complex relative to the amount and noisiness of the input data. The overfitted model has high variance and low bias, making excellent predictions on the training data but performing poorly on new, unseen data because it has essentially memorized the training dataset rather than learning the general underlying patterns.

The name “Lasso regression” comes from the term “Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator.” It was introduced by Robert Tibshirani in 1996 as a new regression method that not only has the capability to shrink the coefficients toward zero, like Ridge regression, but also to set some coefficients exactly to zero. This latter property makes Lasso regression particularly useful for feature selection in addition to regularization.

The term “Lasso” itself is a metaphor, likening the method to a cowboy’s lasso used to catch and select specific components (in this case, variables or features in a model). The lasso wraps around the most important features while discarding the less important ones, making it a valuable tool for models with a large number of features, many of which might be irrelevant or redundant.

5. Logistic Regression method

Logistic regression in biostatistics is a statistical analysis method used to model the relationship between one or multiple independent variables and a dependent variable that is binary (i.e., it takes on two possible outcomes, often coded as 0 and 1). It’s particularly useful in the field of biostatistics for analyzing and predicting the probability of a binary outcome based on one or more risk factors or predictor variables.

Logistic regression is a statistical method used for analyzing a dataset in which there are one or more independent variables that determine an outcome. The outcome is measured with a dichotomous variable (in which there are only two possible outcomes). It’s used extensively in fields like medicine, biology, and social sciences, among others, for tasks like disease prediction, customer churn prediction, and spam detection.

The logistic function, also called the sigmoid function, is an S-shaped curve that can take any real-valued number and map it into a value between 0 and 1, but never exactly at those limits.

6. Entropy in Statistics

In statistics and machine learning, entropy is a measure of uncertainty, randomness, or unpredictability in a set of outcomes. The concept of entropy, borrowed from thermodynamics and information theory, is particularly useful in model fitting and various statistical analyses for quantifying the amount of information, selecting models, and even in decision tree algorithms. Here’s how entropy is applied in these contexts:

Information Gain in Decision Trees:

In the context of decision trees, particularly in classification problems, entropy is used to measure the impurity or disorder in a set of examples. Information gain, which is based on the decrease in entropy, is then used to decide which feature to split on at each step in the tree.

- Entropy before Split: Measures the degree of uncertainty or impurity in the dataset before it is divided.

- Entropy after Split: Measures the weighted sum of the entropy of each subset created after splitting the dataset based on a specific feature.

- Information Gain: The difference between the entropy before the split and the weighted entropy after the split. A feature with the highest information gain is chosen for the split because it best reduces uncertainty.

Model Selection and Regularization:

Entropy can also be used as a criterion for model selection and regularization, particularly in methods like Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt) modeling, which is used in various fields including natural language processing (NLP) and ecology.

- Maximum Entropy Modeling: In MaxEnt, the principle of maximum entropy is used to select the probability distribution that best represents the current state of knowledge (the one with the maximum entropy), subject to the given constraints (e.g., the known moments or expectations of certain features). This approach ensures that no additional assumptions are made beyond what is justified by the data, leading to a model that is maximally non-committal with regard to missing information.

Feature Selection and Dimensionality Reduction:

Entropy can be used to evaluate the importance or relevance of features in a dataset. Features that do not contribute significantly to reducing uncertainty (or increasing the information gain) can be considered for removal, which is an essential aspect of feature selection and dimensionality reduction.

- Mutual Information: A related concept, mutual information, measures the amount of information that one variable provides about another. In feature selection, mutual information can be used to quantify the relevance of each feature with respect to the target variable, where features with higher mutual information are preferred.

Quantifying Prediction Uncertainty:

In probabilistic modeling and Bayesian statistics, entropy can be used to quantify the uncertainty associated with predictions. Models that produce probability distributions as predictions can have their predictive entropy calculated to assess how uncertain the model is about its predictions.

- Predictive Entropy: High entropy in the predicted probability distributions indicates high uncertainty in the predictions, which can be crucial for understanding the confidence of the model in its predictions and for decision-making processes where uncertainty needs to be minimized.

Example in Decision Tree:

Consider a dataset with two features (X1: Color, X2: Size) and a binary target variable (Y: Defective or Not Defective). The entropy of the target variable represents the uncertainty in the defective status. If a split based on the “Color” feature results in subsets with lower entropy (more purity in terms of the target variable), the information gain from this split is high, making “Color” a good candidate for splitting. The decision tree algorithm will use this entropy-based criterion to construct a tree that aims to reduce the uncertainty (entropy) in the target variable with each split.

In summary, entropy serves as a foundational concept in model fitting and statistics, enabling more informed decisions about model structure, feature importance, and the uncertainty in predictions, thereby improving model interpretability and effectiveness.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: