Tsallis Statistics in Logistic Regression

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Boltzmann-Gibbs Statistical Mechanics

- 3. Nonextensive Statistical Mechanics

- 4. Tsallis in Logistic Regression Methods

- Appendix. Useful Mathematical Formulae

1. Introduction

Tsallis statistics is a generalization of traditional statistical mechanics, devised by Constantino Tsallis, to better characterize complex systems. It involves a collection of mathematical functions and associated probability distributions that can be derived by optimizing the Tsallis entropic form, a generalization of familiar Boltzmann entropy. A key aspect of Tsallis statistics is the introduction of a real parameter $q$, which adjusts the distributions to exhibit properties intermediate between Gaussian and Levy distributions, reflecting the degree of nonextensivity of the system.

Tsallis distributions include various families like the $q$-Gaussian, $q$-exponential, and $q$-Weibull distributions. These distributions are notable for their heavy tails and have been applied across diverse fields such as statistical mechanics, geology, astronomy, economics, and machine learning, among others.

The adaptation of Tsallis statistics to these varied fields underscores its versatility in dealing with systems where traditional Boltzmann-Gibbs statistics might not be adequate, particularly in scenarios involving long-range interactions, memory effects, or multifractal structures. Tsallis statistics is particularly useful in the analysis of non-extensive systems, to biostatistics could offer a novel perspective on analyzing complex biological data. Tsallis statistics has been successfully applied in various complex physical systems, such as space plasmas, atmospheric dynamics, and seismogenesis, as well as in the analysis of brain and cardiac activity, showing excellent agreement between theoretical predictions and experimental data. This demonstrates the versatility and potential of Tsallis statistics in capturing the dynamics of complex systems, which could be beneficial in biostatistical applications.

Given the interdisciplinary nature of biostatistics, which often deals with complex, high-dimensional data, the non-extensive framework of Tsallis statistics might offer new methodologies for data analysis. For instance, it could be useful in understanding the dynamics of ecosystems, population genetics, or the spread of diseases, where traditional models might not fully capture the underlying processes due to their complexity and the presence of long-range interactions.

To explore this possibility further, one could start by investigating specific biostatistical problems where the assumptions of traditional statistical mechanics are not met, and then applying Tsallis statistics to see if it offers better predictive power or insights. It would also be beneficial to collaborate with experts in biostatistics to identify the most pressing challenges where Tsallis statistics could be applied.

While the application of Tsallis statistics to biostatistics is an intriguing prospect, it is an emerging area that would require substantial interdisciplinary research to fully understand its potential and limitations. Below is a list of potential applications, which is to be taken with a grain of salt.

-

Epidemiological Modeling: Tsallis statistics could be used to model the spread of diseases, especially in cases where traditional models fail to capture the long-range correlations between individuals in a population.

-

Genetic Data Analysis: Analysis of genetic sequences and variations, where non-extensive entropy might better capture the complexity and long-range dependencies within genetic information.

-

Protein Folding Dynamics: Investigating the non-linear dynamics of protein folding, where Tsallis statistics may offer insights into the anomalous diffusion processes involved.

-

Neural Network Analysis: Modeling the complex interactions within neural networks, particularly in understanding the non-linear dynamics of brain activities and signal transmissions.

-

Ecological Systems: Applying Tsallis statistics to model the complexity of ecological systems, where interactions can span vast spatial and temporal scales.

-

Cancer Growth Modeling: Understanding the anomalous growth patterns of tumors, where traditional models might not accurately capture the underlying dynamics.

-

Drug Response Modeling: Analyzing the variability in drug responses among populations, which may exhibit non-standard distribution patterns that Tsallis statistics could elucidate.

-

Heart Rate Variability Analysis: Investigating the complex, non-linear dynamics of heart rate variability, potentially uncovering new insights into cardiovascular health.

-

Analysis of Medical Imaging Data: Enhancing the interpretation of complex patterns in medical imaging, such as MRI or CT scans, through non-extensive statistical models.

-

Public Health Data Analysis: Applying Tsallis statistics to public health data, potentially uncovering new patterns or correlations in large-scale health trends.

1.1. The Basics of Boltzmann-Gibbs Extensive Entropy

The whole theory of Tsallis statistics is based on a single concept: the modified Boltzmann-Gibbs (B-G) entropy $S_ {q}$. $q$ is some index show how much $S_ {q}$ differs from the $BG$ entropy, if $q=1$ then there is no difference.

To explain why the Boltzmann-Gibbs entropy is said to be additive, let’s first clarify what we mean by entropy in this context. In statistical mechanics, the Boltzmann-Gibbs entropy is a measure of the number of microstates that correspond to a given macrostate, providing a quantification of the system’s disorder or randomness.

The formula for Boltzmann-Gibbs entropy, $S$, for a system in a particular macrostate is given by:

\[S = -k_B \sum_i p_i \ln p_i\]where $p_i$ is the probability of the system being in the $i$-th microstate, and $k_B$ is the Boltzmann constant.

Entropy is said to be additive when, for two independent systems $A$ and $B$, the total entropy $S_{AB}$ of the combined system is the sum of their individual entropies:

\[S_{AB} = S_A + S_B\]This additivity property stems from the assumption of statistical independence of the two systems, which implies that the probability of the combined system $AB$ being in a particular microstate is the product of the probabilities of $A$ and $B$ being in their respective microstates. If $A$ is in a microstate with probability $p_i$ and $B$ is in a microstate with probability $q_j$, then the probability of the combined system being in the microstate characterized by both $p_i$ and $q_j$ is $p_i \cdot q_j$.

As an example, consider two independent systems $A$ and $B$, each with two possible microstates. For system $A$, let the probabilities of the microstates be $p_1$ and $p_2$, and for system $B$, let them be $q_1$ and $q_2$. The entropies of systems $A$ and $B$ are:

\(S_A = -k_B (p_1 \ln p_1 + p_2 \ln p_2)\) \(S_B = -k_B (q_1 \ln q_1 + q_2 \ln q_2)\)

For the combined system $AB$, there are four possible microstates, with probabilities $p_1q_1, p_1q_2, p_2q_1,$ and $p_2q_2$. The entropy of the combined system is:

\[S _{AB} = -k_B [(p_1q_1) \ln (p_1q_1) + (p_1q_2) \ln (p_1q_2) + (p_2q_1) \ln (p_2q_1) + (p_2q_2) \ln (p_2q_2)]\]With some algebra, you can show that:

\[S_{AB} = S_A + S_B .\]This demonstrates the additivity of entropy for independent systems. The crucial point here is the assumption of independence, which allows the probabilities of the combined system to be expressed as products of the individual systems’ probabilities, leading directly to the additivity of entropy.

Tsallis in his book compared his generalization of B-G statistics to $q$-statistics to the generalization of a circle to ellipses in explaining the motion of celestial objects. In both cases a single parameter changes everything. However I would argue that in the case of Kepler and others, more physics was revealed then in Tsallis’ case.

1.2. Generalization to non-Extensive entropy

In his book Tsallis listed some reasons for considering non-extensive, non-Boltzmann-Gibbs entropy, which can be roughly translated into:

- There is no (mathematical or physical) reason not to.

- A statistical description of a system should be based on the dynamics of the system, the macroscopic theory should come from a microscopic one. This opens the way, especially for complex systems, for other than Boltzmann statistics.

- The existence of long-range interactions on the microscopic level.

2. Boltzmann-Gibbs Statistical Mechanics

2.1. Three different forms of BG entropy

No we need to come back to one of the most important concept in physics, statistics and information theory: entropy. It appears in various fields, each with its unique perspective but underlying similarities in concept.

Generally, entropy represents a measure of disorder, randomness, or uncertainty. In statistics, entropy is a measure of the unpredictability or the randomness of a distribution. The higher the entropy, the more unpredictable the outcome. For example, in a perfectly uniform distribution where all outcomes are equally likely, entropy is at its maximum, indicating maximum uncertainty or disorder. In contrast, a distribution where one outcome is certain has zero entropy, representing complete order. This concept is used in various statistical methods and models to quantify uncertainty or variability within a dataset. In information theory, entropy is a fundamental concept introduced by Claude Shannon. It quantifies the average amount of information produced by a stochastic source of data. The more uncertain or random the source, the higher the entropy. In practical terms, entropy helps in understanding the limits of data compression and the efficiency of communication systems. For instance, a message composed of completely random bits has higher entropy and cannot be compressed beyond a certain limit without losing information. On the other hand, a message with a lot of repetitive or predictable parts has lower entropy and can be compressed more effectively.

In each of these fields, entropy helps us understand systems’ behavior in terms of unpredictability, disorder, and efficiency. While the context and applications may vary, the core idea revolves around the concepts of uncertainty and the distribution of states or outcomes.

In the previous section we showed the definition of entropy without much justification, because there is none! Not from the first principal at least. The programme to derive the expression of entropy that we are using today is sometimes called the Boltzmann program, since that was what Boltzmann was trying to do, before he strangled himself to death using a curtain or something.

However, if the possibilities is a continuous distribution, the BG entropy must be modified accordingly, discrete probability $p_ {i}$ must be replaced by probability density $p(x)$ where $x$ is the variable. As a naively guess, I would say that we can write the entropy as

\[-k \sum p _ {i} \ln p _ {i} \to -k \int dx \, p(x) \ln(p(x)),\]where the probability distribution function (or probability density) is normalized,

\[\int dx \, p(x) =1.\]However, a difference between discrete and continuous probability lies in its dimension! Normalized discrete probabilities $p_ {i}$ sums to 1, $\sum_ {i} p_ {i}=1$, since $1$ is dimensionless, so is $p_ {i}$. This is not true for continuous probability density $p(x)$, since now the normalization condition tells us that $\int dx \, p(x)$ should be dimensionless, and $dx$ has the dimension of length, so $p(x)$ must have dimension of length inversed! Thus, wo need to introduce another parameter, call it $\sigma$, with dimension of length. Then we can define the BG entropy in the continuous scenario:

\[S_ {BG} = -k\int dx \, p(x) \ln(\sigma\, p(x)).\]For the case of equal probabilities, that is, $p= 1 / \Omega$ where $\Omega$ is the total number of allowed microscopic states, we have

\[S_ {BG} = k \ln\left( \frac{\Omega}{\sigma} \right).\]We just mention on the fly that, in quantum mechanics, the probabilistic distribution of a mixed state in terms of pure states is described using the density matrix $\rho$, and the BG entropy is generalized to

\[S_ {BF} = -k\,\mathrm{Tr}\, (\rho \ln \rho).\]2.2. Properties of BG entropy

We will list without proof some of the key properties of BG entropy.

- Non-negativity. $S\geq 0$ always. $S = k\ln \Omega$ might help to convince you of it.

- BG entropy is maximized at equal probability. Anything that drives the system away from it will decrease the entropy.

- Expansibility. Adding to a system new possible states with zero probability should not modify the entropy.

- Additivity. Let $A,B$ be two systems with entropy $S(A)$ and $S(B)$, putting them together will result in a new system $A+B$ with entropy $S(A+B)=S(A)+S(B)$.

- Concavity. Given two different probability distributions $\left\lbrace p_ {i} \right\rbrace$ and $\left\lbrace p’_ {i} \right\rbrace$, we can define an intermediate probability distribution

Then we have

\[S(\widetilde{p})\equiv S(\lambda)> \lambda S(p)+(1-\lambda)S(p').\]Shannon Uniqueness Theorem.

In his work, Shannon was interested in finding a measure that could quantitatively capture the information content of a message source. He proposed several properties that this measure (which we now call entropy) should satisfy to be a useful and consistent measure of information. These properties included:

- Additivity: The entropy of two independent sources should be the sum of their individual entropies.

- Continuity: The measure should change continuously as the message probabilities change.

- Symmetry: The measure should not depend on the order of the messages.

- Maximum: The measure should be maximal for a uniform distribution, where all messages are equally likely.

Shannon’s Uniqueness Theorem essentially states that, given these properties (along with a few others), the entropy of a discrete random variable is unique and is given by the now-familiar formula:

\[S = -\sum_{i} p(x_i) \ln p(x_i)\]The theorem’s significance lies in its establishment of entropy as a unique measure that satisfies these intuitive and necessary properties for quantifying information. It solidified the concept of entropy as the foundational metric in information theory, leading to profound implications for communication, coding theory, and even other disciplines like statistics and thermodynamics.

2.3. Constraints and Entropy Optimization

Imposing the Mean Value

We might know a priori the mean value of a variable $x$, i.e.

\[\left\langle x \right\rangle := \int dx \, x \, p(x) = \overline{x} \quad \text{ is known.}\]We can apply the Lagrange multiplier method to find the optimizing distribution with the constraint, together with the normalization condition $\int dx \, p(x)=1$. The Lagrangian functional that we want to extremize reads

\[\Phi[p(x)] = S_ {BG} - \alpha \int dx \, p(x) - \beta \int dx \, x \, p(x)\]where we have neglected some constant terms since they don’t appear in the Euler-Lagrange equation, that is to say, they don’t affect the final result; and

\[S_ {BG} = -\int dx \, p(x)\ln p(x).\]Using the method of variation, we get

\[p(x) = \frac{1}{\overline{x}} e^{ -x / \overline{x} }.\]Imposing the Mean value and the Mean Squared Value

Supposed that we not only know the mean value $\overline{x}=\left\langle x \right\rangle$, but also the mean square value $\left\langle x^{2} \right\rangle$:

\[\left\langle x^{2} \right\rangle \equiv \int dx \, (x-\left\langle x \right\rangle )^{2} p(x)\]This time the Lagrangian reads

\[\Phi[p(x)] = S_ {BG} - \alpha \int dx \, p(x) - \beta_ {1}\int dx \, xp(x) - \beta_ {2} \int dx \, (x-\left\langle x \right\rangle )^{2}p(x).\]Exactly as before, the variational method gives us

\[p(x) = \sqrt{ \frac{\beta_ {2}}{\pi} } \exp \left\lbrace -\beta_ {2}(x-\left\langle x \right\rangle )^{2} \right\rbrace\]which is just the Gaussian distribution! This tells us that the Gaussian distribution maximizes the entropy with fixed mean and variance.

3. Nonextensive Statistical Mechanics

Tsallis is convinced that there exists no logical-deductive procedure for generalizing any physical theory. As a possible motivation to generalize the exponential function $e^{ x }$, he started from the equation that $e^{ x }$ satisfies, which is fairly simple:

\[\frac{dy}{dx} = y.\]A possible generalization of the equation is to writhe the RHS as $a+by$, we have

\[\frac{dy}{dx} = a+by \implies \frac{dy}{a+by}=dx\implies y=\frac{1}{b}(e^{ b(x+c) }-a),\]which does not look very promising. Then Tsallis considered a non-linear generalization:

\[\frac{dy}{dx} = y^{q}, \quad q\in \mathbb{R},\quad y(0)=1.\]The boundary condition $y(0)=1$ is such that is agrees with the usual exponential function $e^{ 0 }=1$. Solving it we get

\((1-q) (x+c) = y^{1-q} ,\) the boundary condition translates to

\[c = \frac{1}{1-q},\]thus

\[\boxed{ y = (1+(1-q)x)^{1/(1-q)} =: \exp_ {q}(x). }\]When $1+(1-q)x<0$, $e_ {q}(x)$ is defined to be zero (why don’t complexify it?). Also note that $e^{ x }_ {q}$ goes to $e^{ x }$ at $q\to 1$ since, writing $q = 1-\epsilon$, we have

\[\lim_ { q \to 1 } e^{ x }_ {q} = \lim_ { \epsilon \to 0 } (1+\epsilon x)^{1/\epsilon} = e^{ x }.\]From the same equation that we got the definition of $e^{ x }_ {q}$, we also get the inverse function of $x$ in terms of $y$:

\[\boxed{ x = \frac{y^{1-q}-1}{1-q} =: \log_ {q} y. }\]They are referred to as $q$-exponential functions and $q$-logarithmic functions respectively.

Recall that logarithmic functions turns multiplication into addition, $\log(AB)=\log(A)+\log(B)$, for $q$-logarithmic functions we have something similar,

\[\log_ {q}(AB) = \log_ {q}(A) + \log_ {q}(B) + (1-q) \log_ {q}(A)\log_ {q}(A).\]3.1. Mean Value in Tsallis Statistics

The Tsallis entropy is defined as

\[S_ {q} = \frac{1}{q-1} \sum_ {i} (p_ {i}-p_ {i}^{q}) = - \sum_ {i} p_ {i} \ln_ {q} p_ {i}\]There are at least three types of Tsallis statistics, depending on how they take the mean value. Next we will discuss each of them in chronological order.

Throughout the note we will assume that probabilities are normalized to one,

\[\sum_ {i} p_ {i} = 1.\]Given an observable $\mathcal{O}$, what is the expected value $\left\langle \mathcal{O} \right\rangle$? In regular statistics

\[\left\langle \mathcal{O} \right\rangle := \sum_ {i} p _ {i} O_ {i}\]where $\mathcal{O}_ {i}$ is the $i$-th possible value of $\mathcal{O}$ with probability $p_ {i}$. However, this definition yields an ill-defined thermodynamic distribution, some energy states will not be allowed due to mathematical rather than physical reasons, and the distribution is not invariant under an overall shift in energy. Normally only the energy difference matter, the only situation that I know of where the absolute energy matters is from gravity, which is clearly not the case here. Thus it is not a good definition in Tsallis statistics.

Another way to define the average, known as Tsallis type II, is

\(\left\langle \mathcal{O} \right\rangle := \sum_ {i} p_ {i}^{q} \mathcal{O}_ i.\) The problem is similar with type I, the sample space is constraint due to some un-natural reason, which I tend to interpret as the evidence of an ill-defined theory. Some divergence that occurs in type I does not occur here, but it introduces new problems, most of all the expected value of unity $\mathbb{1}$ is not $1$.

However there is a remedy. Arguing from the point of view of information theory on incomplete probability distributions, Q. A. Wang suggested modifying the normalization of probability as

\[\sum_ {i} p_ {i}^{q} = 1.\]This can be rewritten by defining $P_ {i}:= p_ {i}^{1}$, then

\[\left\langle \mathcal{O} \right\rangle := \sum_ {i} P_ {i} \mathcal{O}_ {i} .\]Type III assumes that the average is defined as type II but with an normalization factor:

\[\left\langle \mathcal{O} \right\rangle := N \sum_ {i} p_ {i}^{q}\mathcal{O}_ {i},\quad N = \sum_ {i}p_ {i}.\]This solves the problem that the expectation value of identity $1$ is not $1$. The probability derived from is also becomes invariant under an overall shift.

4. Tsallis in Logistic Regression Methods

This part will be presented in a much less pedagogical way, we will simply introduce new functions and concepts along the way.

Before I could apply Tsallis statistics to medical data, I need first to figure out how the traditional method works.

4.1 Traditional logistic regression method

Consider a matrix $X_ {n \times p}$ representing the expression of $p$ genes from $n$ samples, obtained through technologies like microarray or RNA-seq. Here, $p \gg n$, hence the name big $p$, small $n$ problem. The response, or dependent variables (observables), is denoted by an $n$-vector $\vec{y} = (y_ 1, \cdots, y_ n)$. Each $y_ i$ is a binary variable, taking values 0 or 1. For example, in a clinical context, think of each sample as a patient; $y_ i = 1$ might indicate that patient $i$ is cured of, or has, a certain disease, while $y_ i = 0$ indicates the opposite. Currently, we are focusing on a mathematical model, so the exact biological or clinical significance of $y = 1$ is not specified. The values of $\vec{y}$ follow a Bernoulli distribution, which will be discussed in more detail shortly.

We can organize all the gene expressions from all the samples into a single matrix $X$,

\[X = \begin{pmatrix} x_ {11} & \cdots & x_ {1p} \\ x_ {21} & \cdots & x_ {2p} \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ x_ {n1} & \cdots & x_ {np} \end{pmatrix}.\]In the above matrix, each row is a vector of different genes from one sample, while each column represents one type of gene from different patients. We use $X_ {i}$ to denote the expression of the $i$-th gene across $n$ samples, which corresponds to the $i$-th column of $X$. Conversely, $(X_ {(j)})^{T}$ represents the genes expression observed in $j$-th sample (or patient $j$), namely the $j$-th row of $X$. The transpose makes $X_ {(j)}$ a column vector, just like $X_ {a}$. Be aware that the distinction in notation is merely the addition of parentheses. In general, $X$ is our data and $\vec{y}$ will be the dependent variable. In practice, it is known which patients are treated and which are not, hence we know the observed value of $\vec{y}$. The problem is to find a way to predict $y_ {a}$ from an observed vector of genes expressions $X_ {(a)}$. But first, we need to know the role played by each gene expressed in different patients, that is, we need to know how to interpret $X_ {a}$ for gene $a$. For example, if $X_ {a}$ is a constant vector for all the patients, then we know that gene $a$ most likely has nothing to do with the disease of study.

Let us now delve into the mathematical foundations of the model.

Let $\pi_ {i}$ be the probability of $y_ {i}=1$, which we aim to predict. Following the standard logistic regression method, we define the logit (log here is used as a verb, log-it) function of $\pi_ {i}$,

\[\text{logit}(\pi_ {i} ) := \ln\left( \frac{\pi_ {i}}{1-\pi_ {i}} \right), \quad \text{logit}: [0,1]\to \mathbb{R}.\]$\pi$ is the probability, and $\pi / (1-\pi)$ is called odd with range $\mathbb{R}^{+}:=[0,\infty)$. Note that in our convention zero is included in $\mathbb{R}^{+}$.

Since we have constructed a continuous function $\text{logit}(\pi)$ from a probability function $\pi$, we can now adopt familiar linear regression method and apply it to the logit function. Parametrize the logit function in a linear form

\[\text{logit}(\pi_ {i}) := \beta_ {0}+X_ {(i)}\cdot\beta, \quad \beta=(\beta_ {1},\cdots,\beta_ {p}).\]$\beta$ is the parameter vector to be fixed later. Note the dot product is the product between vectors, $X \cdot \beta:= X^{T} \beta$ .

Direct derivation shows that

\[\pi_ {i} = \frac{1}{1+\exp(-\beta_ {0}-X_ {(i)}\cdot \beta)}=:\text{sigm}(\beta_ {0}+X_ {(i)}\cdot \beta),\]where $\text{sigm}$ stands for sigmoid function, which literally means a function that has an $S$-shape. In our particular case the sigmoid function is give by

\[\text{sigm}(t) := \frac{1}{1+e^{ -t }}.\]Note that $\text{sigm}$ is the inverse of $\text{logit}$,

\[\text{logit}(\pi)=x \Longleftrightarrow \pi = \text{logit}^{-1}(x) = \text{sigm}(x).\]I am not sure if there exists other widely-applied definitions for sigmoid function except for that given above. There surely are other functions with an S-shape, such as tanh and arctan, but I am not sure if they can be called sigmoids? Or maybe difference in the predictive power by introducing different choices of sigmoid functions are negligible, hence it only makes sense that we stuck with the simplest option?

Now, the question is how can we fix the parameters? The natural answer is: by maximizing the likelihood, or equivalent by minimizing the loss function. The likelihood function, by definition, is the probability (likelihood) for a certain observation $\vec{y}$. This function gives the probability of observing the given data within certain model, with some free parameters. For instance, supposed there are three samples (binary), then the likelihood of $y=(1,0,1)$ corresponds to the probability predicted by our model that the first and third patients have got some disease, while the second does not. Now, the probability for each $y_ {i}=1$ is $\pi_ {i}$, which is by definition $\text{sigm}(t_ {i})\equiv1/(1-e^{ -t_ {i} })$, where $t=\beta_ {0}+X_ {(i)}\cdot \beta$, and $\beta$’s are the parameters. The probability for $y_ {i}=0$ is $1- 1/(1-e^{ -ti })$, which is $e^{ -t_ {i} }/(1-e^{ -t_ {i} })$. Then, the likelihood for observing $y=(1,0,1)$ is simply the product of each probability,

\[\text{lik}(1,0,1) = \frac{1}{1-e^{ -t_ {1} }} \frac{e^{ -t_ {2} }}{1-e^{ -t_ {2} }} \frac{1}{1-e^{ -t_ {3} }},\]which is a function of observed gene expression $X_ {(i)}$ with parameters $\beta$’s.

Likelihood function can also be written using the Bernoulli distribution function, which is a probability distribution function (PDF) that has only two possible outcomes, 1 and 0, with probability $\pi$ for $y=1$ and $1-\pi$ for $y=0$. This distribution is a special case of the binomial distribution where the number of trials $n$ is equal to 1. The Probability Mass Function (PMF) of Bernoulli distribution is defined as

where $\pi$ is given a priori. The Expected Value is $\left\langle y \right\rangle=\pi$ and the variance is $\text{Var}(y) = \pi(1-\pi)$, you can verify it easily. This neat expression unites both cases $y=0$ and $y=1$. Applying it to the likelihood function we get

\[\text{lik}(1,0,1) = \prod_ {i=1}^{3} \pi_ {i}^{y_ {i}}(1-\pi_ {i})^{1-y_ {i}}, \quad \vec{y}=(1,0,1).\]Generalization to arbitrary $\vec{y}$ is trivial,

\[\text{lik}(\vec{y}) := \prod_ {i=1}^{n} \pi_ {i}^{y_ {i}}(1-\pi_ {i})^{1-y_ {i}}, \quad \vec{y}=(y_ {1},\cdots,y_ {n}).\]The above expression can be further simplified using logarithms. Recall that logarithm is a monotonically increasing function, it means that $\log(\text{lik}(\vec{y}))$ is maximized iff (if and only if) $\text{lik}(\vec{y})$ is maximized. The reason why it is a good idea to take the logarithm of the likelihood is the following.

-

Numerical Stability: The likelihood function in models like logistic regression involves products of probabilities, which can be very small numbers. When multiplying many such small probabilities, the result can become extremely small, potentially leading to numerical underflow (where values are so small that the computer treats them as zero). The logarithm of these small numbers turns them into more manageable, larger negative numbers, reducing the risk of numerical issues.

-

Simplification of Products into Sums: The likelihood function involves taking the product of probability values across all data points. In contrast, the log-likelihood converts these products into sums by the property of logarithms $\ln(ab) = \ln(a) + \ln(b)$. Sums are much easier to handle analytically and computationally. This is especially useful when dealing with large datasets.

-

Convexity Properties: The log-likelihood function often yields a convex optimization problem in cases where the likelihood itself is not convex. Convex problems are generally easier to solve reliably and efficiently. For logistic regression, the log-likelihood function is concave, and finding its maximum is a well-behaved optimization problem with nice theoretical properties regarding convergence and uniqueness of the solution.

-

Derivative Computation: The derivatives of the log-likelihood (needed for optimization algorithms like gradient ascent or Newton-Raphson) are typically simpler to compute and work with than the derivatives of the likelihood function. This simplicity arises because the derivative of a sum (log-likelihood) is more straightforward than the derivative of a product (likelihood).

Last but not least,

- Possibility to introduce the Tsallis statistics: We have explain how the Tsallis statistics modified traditional exponential and logarithmic functions, in our case the log-likelihood function can be generalized by adopting the Tsallis logarithm, namely $\log_ {q}$. In the next section we will try to explain the advantage of such generalization, which will also serve as justification. But of course, being a phenomenological model, the true justification will be the power of prediction, which can only be tested in real-life practice.

But for now, let’s forget about Tsallis and carry on on the road of conventional logic regression method.

Taking the natural log of likelihood function gets us

\[\begin{align*} \text{loglik}(\vec{y}) &:=\log(\text{lik}(\vec{y}))= \ln \left\lbrace \prod_ {i=1}^{n} \pi_ {i}^{y_ {i}}(1-\pi_ {i})^{1-y_ {i}} \right\rbrace \\ &=\sum_ {i} \left\lbrace y_ {i} \ln\pi_ {i}+(1-y_ {i}) \ln(1-\pi_ {i}) \right\rbrace. \end{align*}\]In the context of logistic regression, people often use the loss function, defined as the negative of the likelihood function. This is primarily due to convention and practical considerations in optimization processes, since most optimization algorithms and tools are designed to minimize functions rather than maximize them. This is a common convention in mathematical optimization and numerical methods. Since maximizing the likelihood is equivalent to minimizing the negative of the likelihood, formulating the problem as a minimization problem allows us the application of standard, widely available optimization software and algorithms without modification. In many statistical learning methods, the objective function is often interpreted as a “cost” or “loss” that needs to be minimized. When working with a loss function, the goal is to find parameter estimates that result in the smallest possible loss. Defining the loss function as the negative log-likelihood aligns with this interpretation because lower values of the loss function correspond to higher likelihoods of the data under the model.

Furthermore, using a loss function that is to be minimized creates a consistent framework across various statistical learning methods, many of which inherently involve minimization (like least squares for linear regression, and more complex regularization methods in machine learning). This consistency is helpful not only from an educational and conceptual standpoint but also from a practical implementation standpoint.

A regularized loss function is the loss function with penalty terms. Penalty terms in regression methods are essential for managing several challenges that arise in statistical modeling, particularly with high-dimensional data. These challenges include overfitting, multicollinearity, and interpretability.

One of the primary reasons for using penalty terms is to prevent overfitting. Overfitting occurs when a model captures not just the true underlying pattern but also the random fluctuations (noise) in the data. This makes the model very accurate on the training data but poorly generalized to new, unseen data. By adding a penalty term, which increases as the model complexity increases (e.g., as coefficients become larger), the optimization process is biased towards simpler models. This helps to ensure that the model generalizes well to new data by focusing on the most significant predictors and shrinking the others.

Multicollinearity occurs when two or more predictor variables in a regression model are highly correlated. This can make the model estimation unstable and the estimates of the coefficients unreliable and highly sensitive to small changes in the model or the data. Penalty terms, especially those like Lasso regression (L1 penalty) or Ridge regression (L2 penalty), can reduce the impact of multicollinearity by penalizing the size of the coefficients, thus stabilizing the estimates. In high-dimensional datasets where the number of predictors $p$ exceeds the number of observations $n$ or when there are many irrelevant features, selecting the most relevant features becomes crucial. Lasso regression (L1 penalty) is particularly useful for this purpose because it can shrink some coefficients to exactly zero, effectively performing variable selection. This helps in identifying which predictors are most important for the outcome, simplifying the model and improving interpretability.

By shrinking coefficients or reducing the number of variables, penalty terms help in simplifying the model. A simpler model with fewer variables or smaller coefficients is easier to understand and interpret. This is particularly valuable in domains like medical science or policy-making, where understanding the influence of predictors is as important as the prediction itself.

However it is also important to realize the disadvantages of introducing penalty terms, that is the bias-variance tradeoff. Adding a penalty term introduces bias into the estimator for the coefficients (the estimates are “shrunk” towards zero or towards each other in the case of Ridge). However, this can lead to a significant reduction in variance (the estimates are less sensitive to fluctuations in the data). This trade-off can lead to better predictive performance on new data, which is the ultimate goal of most predictive modeling tasks.

In our project, we consider the regularized loss function as following.

\[l(\beta_ {0}, \vec{\beta}) := -\sum_ {i}^{n} \left\lbrace y_ {i}\ln(\pi_ {i})+(1-y_ {i})\ln(1-\pi_ {i}) \right\rbrace +h(\vec{\beta}),\]where $h(\vec{\beta})$ is the penalty terms and is independent of $\beta_ {0}$, which is simply a shift. $h(\vec{\beta})$ could be the Lasso (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) term, or ridge term.

We now introduce the Group Lasso regression method. Group Lasso regression is an extension of Lasso that is particularly useful in the context of biostatistics, especially when dealing with models that incorporate multiple predictors which naturally group into clusters. This method not only encourages sparsity in the coefficients, like traditional Lasso, but also takes into account the structure of the data by promoting or penalizing entire groups of coefficients together. Here’s an introduction to how Group Lasso works and why it’s valuable in biostatistics:

In many biostatistical applications, predictors can be inherently grouped based on biological function, measurement type, or other domain-specific knowledge. For example, genes might be grouped into pathways, or clinical measurements might be grouped by the type of instrument used or the biological system they measure.

The key idea behind Group Lasso is to perform regularization and variable selection at the group level. The formulation of Group Lasso is similar to that of Lasso, but instead of summing the absolute values of coefficients, it sums the norms of the coefficients for each group. The objective function for Group Lasso can be written as:

\[\text{Minimize:} \quad \text{loss function} + h(\vec{\beta}), \quad h(\vec{\beta}):= \lambda \sum_ {g=1}^G w_ g \left\lVert \vec{\beta}_{(g)} \right\rVert_ {2}\]where $\vec{\beta}$ represents the coefficient vector, $\vec{\beta}_ {(g)}$ is the sub-vector of coefficients corresponding to group $g$. Note the difference between $\beta_ {g}$ and $\beta_ {(g)}$, the former is a component of $\vec{\beta}$ thus a number, while the latter is a sub-vector of $\vec{\beta}$. $G$ is the total number of groups, $w_g$ are weights that can be used to scale the penalty for different groups, often based on group size or other criteria, $\left\lVert \vec{\beta}_ {(g)} \right\rVert$ is typically the Euclidean norm (L2 norm) of the coefficients in group $g$ or, as is shown in ShunJie’s paper, the PCC (Pearson correlation coefficient) distance, or shape-based distance. $\lambda$ is a global tuning parameter that controls the overall strength of the penalty.

In our current project, we use square root of the degree of freedom (dof) as the weight for different groups. The penalty term is then

\[h(\beta) = \lambda \sum_ {g=1}^{G} \sqrt{ d_ {g} } \left\lVert \vec{\beta}_ {g} \right\rVert _ {2} =: \lambda \sum_ {g=1}^{G} \sqrt{ d_ {g} }\; r_ {g}\]where $d_ {g}$ is the number of genes in group $g$, or dimension of $\vec{\beta}_ {g}$, $\vec{\beta}_ {g}$ is treated as a $d_ {g}$-vector of parameters, and $r_ {g}$ is the radius of $\vec{\beta}_ {g}$. Naturally it is a subset of $\beta$.

Recall that $\sqrt{ d_ {g} }$ is the expected length of $d_ {g}$ i.i.d. variables, independent and identically distributed variables. The factor $\sqrt{d_ g}$ is to adjust for the size of each group, it scales up the penalty proportional to the group size. This means that larger groups, which naturally have a potentially larger norm due to more coefficients, receive a proportionally larger penalty. By multiplying the norm by $\sqrt{d_ g}$, the intention is to make the penalty fair by ensuring that the regularization is proportional to the number of parameters in the group. Without this scaling, smaller groups could be unfairly penalized in relative terms because their norms are naturally smaller due to fewer components. For example, consider two groups in a regression setting:

- Group 1: Contains 1 coefficient, $\mathbf{w}_ 1 = (3)$.

- Group 2: Contains 4 coefficients, $\mathbf{w}_ 2 = (1, 1, 1, 1)$.

Without any normalization, we have

- The norm for Group 1 is $\left\lVert w_ {1} \right\rVert_ 2 = \left\lvert 3 \right\rvert = 3$.

- The norm for Group 2 is $\left\lVert w_ {2} \right\rVert_ 2 = \sqrt{1^2 + 1^2 + 1^2 + 1^2} = 2$.

Here, the raw norms suggest that Group 1 might be more significant, which could distort the model’s view. Using $d_ g$ for normalization instead, we have:

- For Group 1: $1 \times \left\lvert 3 \right\rvert= 3$.

- For Group 2: $4 \times 2 = 8$.

This overcorrects, making the penalty overly sensitive to the number of components, and could lead to under-penalizing smaller groups. Thus we decide to use $\sqrt{d_ g}$ for normalization:

- For Group 1: $\sqrt{1} \times 3 = 3$.

- For Group 2: $\sqrt{4} \times 2 = 2 \times 2 = 4$.

This balances the penalties more reasonably, reflecting that while Group 2 is larger, its collective contribution should be seen in proportion to the natural growth of norms with group size, not exponentially with each addition.

We recall that $X_ {(i)}$ is the expression of different genes from one patient $i$, in terms of $X_ {(i)}$ is given the probability:

\[\pi_ {i} = \frac{1}{1+\exp(-\beta_ {0}-X_ {(i)}\cdot \beta)}=\text{sigm}(\beta_ {0}+X_ {(i)}\cdot \beta)=\text{sigm}(t_ {i} ),\]where the sigmoid function is give by

\[\text{sigm}(t_ {i} ) := \frac{1}{1+e^{ -t_ {i} }}, \quad t_ {i} := \beta_ {0}+X_ {(i)}\cdot \beta.\]The loss function is given by the negative log-likelihood function plus the penalty term, including a punish term:

\[\begin{align*} l(\beta) &= -\sum_ {i}^{n} \left\lbrace y_ {i}\ln(\pi_ {i})+(1-y_ {i})\ln(1-\pi_ {i}) \right\rbrace +h(\vec{\beta})\\ &= -\sum_ {i}^{n} \left\lbrace y_ {i}\ln(\text{sigm}(t_ {i} ))+(1-y_ {i})\ln(\text{sigm}(-t_ {i} )) \right\rbrace +h(\vec{\beta})\\ &= -\sum_ {i} \left\lbrace y_ {i}\ln\left( \frac{\text{sigm}(t_ {i} )}{\text{sigm}(-t_ {i} )} \right) + \ln\, \text{sigm}(-t_ {i} ) \right\rbrace + h(\beta) \\ &= -\sum_ {i}[y_ {i}t_ {i} -\ln(1+e^{ t_ {i} })] + h(\beta)\\ &=: J(\beta)+h(\beta), \end{align*}\]where in the first line we have exploit the fact that the sigmoid function is symmetric, and write $l(\vec{\beta})$ in terms of sigmoid function for future convenience. To be specific, in future work we will consider generalization for sigmoid function with Tsallis q-logarithms, so we might just write the loss functions explicitly in terms of it as well. $h(\beta)$ is the Lasso penalty term given by $\lambda \sum_ {g=1}^{G} \sqrt{ d_ {g} } \left\lVert \vec{\beta}_ {g} \right\rVert _ {2}$. $J(\beta)$ is the minus likelihood function,

\[\boxed{ J(\beta):= -\sum_ {i}[y_ {i}t_ {i} -\ln(1+e^{ t_ {i} })],\quad t_ {i} =\beta_ {0}+\beta \cdot X_ {(i)}. } ,\]As usual, the loss function is convex and non-linear. Since we took the absolute value of $\left\lVert \vec{\beta}_ {g} \right\rVert$, it is not smooth at $\vec{\beta}=0$. However it is not a big problem in minimization problem, since it is piece-wise smooth, we simply need to consider the behavior from both sides of the non-smooth point. In the case of a LASSO punish term, that is the origin or each $\vec{\beta}_ {g}$.

For Group LASSO regression, the goal is to apply LASSO regularization to groups of coefficients rather than individual coefficients. This means entire groups of variables can be zeroed out together, which encourages group-wise sparsity in the model. The challenge with Group LASSO is the non-differentiability of the regularization term, similar to standard LASSO but applied to norms of groups of coefficients.

Several methods can be used to solve the Group LASSO problem efficiently:

-

Coordinate Descent: This method can still be adapted for Group LASSO by modifying it to work on groups of coefficients rather than individual coefficients. In this context, the update step involves a group soft-thresholding operation, which is a generalization of the soft-thresholding used in standard LASSO.

-

Proximal Gradient Methods: These are particularly well-suited for Group LASSO due to their ability to handle non-smooth terms efficiently. The proximal operator for the Group LASSO regularization term can be defined explicitly, allowing for straightforward implementation. This method iteratively updates the coefficients by taking a gradient step on the differentiable loss function and then applying the proximal operator to handle the group sparsity.

-

Block Coordinate Descent: This is a variant of coordinate descent that updates blocks (or groups) of variables at once rather than individual variables. It is particularly useful in Group LASSO, where you want to consider the impact of an entire group of variables together when deciding on updates.

-

Primal-Dual Methods: These methods work by simultaneously updating primal and dual variables to find a solution that satisfies the optimality conditions for both. They can be very efficient for problems like Group LASSO, where the structure of the groups can be exploited to simplify the dual problem.

Among these methods, Proximal Gradient Methods and Block Coordinate Descent are often the most effective for solving Group LASSO due to their ability to directly handle the group-wise structure and non-smoothness of the regularization term. The choice between these methods may depend on the specific structure of your problem and the size of your data. In the following, we will go through some basic methods leading to the proximal gradient method. For a more detailed introduction see the wonderful online course here.

Gradient Descent (GD) method

Gradient Descent is an iterative optimization algorithm used to minimize an objective function, which is often used in various statistical and machine learning methods. In biostatistics, it is commonly used for fitting models such as linear regression, logistic regression, and many others.

Key Concepts:

-

Objective Function: The function you want to minimize, usually representing the error or cost associated with the model. For instance, in linear regression, it is the sum of squared errors.

-

Gradient: The gradient of the objective function at a given point indicates the direction of the steepest ascent. Since we want to minimize the function, we move in the opposite direction of the gradient.

-

Learning Rate: A hyperparameter that controls the size of the steps taken to reach the minimum. If it’s too large, the algorithm might overshoot the minimum; if too small, convergence might be slow.

The basic steps of the gradient descent algorithm are:

- Initialize: Start with an initial guess for the parameters.

- Compute Gradient: Calculate the gradient of the objective function with respect to the parameters.

- Update Parameters: Adjust the parameters in the opposite direction of the gradient.

- Repeat: Continue until convergence (i.e., when the changes in the parameters become very small).

Mathematically, the update rule for the parameter $\beta$ is:

\[\beta^{(t+1)} = \beta^{(t)} - \alpha \nabla f(\beta^{(t)}),\]where $\alpha$ is the learning rate or step length, and $\nabla f(\beta^{(t)})$ is the gradient of the objective function at $\beta^{(t)}$. The derivation of above iteration formula is not as straightforward as, e.g. Newton method, especially it is not clear where the step length comes from. Given a function $f(\beta)$ that we want to minimize, at $\beta^{(k)}$ we are actually approximating it with a quadratic functon

\[g(\beta) = f(\beta^{(k)}) + \nabla f(\beta^{(k)})(\beta-\beta^{(k)}) + \frac{1}{2\alpha}(\beta-\beta^{(k)})^{2},\]note we have introduced the step-size parameter $\alpha$ to control the strength of the quadratic term. To find the minimum of $g(\beta)$ around $\beta^{(k)}$, we ask its derivative to be zero, leading to

\[g'(\beta) = \nabla f(\beta^{(k)}) + \frac{1}{\alpha} (\beta-\beta^{(k)}) =0\]whose solution reads

\[\Delta \beta := \beta-\beta^{(k)} = -\alpha \nabla f(\beta^{(k)}).\]We use $\Delta \beta$ to update $\beta$, namely $\beta^{(k+1)}:= \beta^{(k)}+\Delta \beta$. That’s where the step size parameter comes from. In practice, we usually choose $\alpha=\nabla^{2}f(\beta^{k})$. To make the iteration procedure convergent, there is usually an upper limit for $\alpha$, which is clearly shown in the example of $f(\beta)=\beta^{2}-3\beta+4$, which I’ll skip here, interested readers can take it as a homework.

Let’s go through a simple example of fitting a linear regression model using gradient descent. Suppose we have a dataset with $n$ observations and one predictor. The objective function (mean squared error) is:

\[f(\beta_ 0, \beta_ 1) = \frac{1}{2n} \sum_ {i=1}^n (y_ i - (\beta_ 0 + \beta_ 1 x_ i))^2,\]where $(x_ i, y_ i)$ are the data points, and $\beta_ 0$ and $\beta_ 1$ are the parameters to be estimated.

- Gradient Calculation:

- The gradient with respect to $\beta_ 0$ is:

- The gradient with respect to $\beta_ 1$ is:

- Update Rules:

- Update $\beta_ 0$:

- Update $\beta_ 1$:

Subgradient Method

The subgradient method is an optimization technique used for minimizing non-differentiable convex functions. It is a generalization of the gradient descent method. Instead of using gradients, it uses subgradients, which are generalizations of gradients for non-differentiable functions. A very nice introduction of subgradients and subdifferential can be found here, in the following we only outline the key concepts.

Key Concepts:

- Subgradient: For a convex function $f$ at a point $x$, a vector $g$ is a subgradient if:

-

Subdifferential: The set of all subgradients at $x$, denoted $\partial f(x)$.

-

Update Rule: The algorithm iteratively updates the solution using

where $g^{(k)} \in \partial f(x^{(k)})$ and $\alpha_ k$ is the step size.

Example: Minimizing $f(x) = \left\lvert x \right\rvert$

-

Function Definition: $f(x) = \left\lvert x \right\rvert$

- Subgradient Calculation:

- For $x > 0$, $\partial f(x) = { 1 }$

- For $x < 0$, $\partial f(x) = { -1 }$

- For $x = 0$, $\partial f(x) = { t \mid -1 \leq t \leq 1 }$

- Subgradient Method Steps:

- Initialize $x^{(0)} = 2$

- Choose a step size $\alpha = 0.1$

- Iterate the update rule:

-

Suppose $g^{(k)} = 1$ for simplicity.

-

First iteration:

- Second iteration:

- Continue iterating until $x$ converges to 0.

However, there might be some convergence problem in the last step. Instead of converging to the actual minimum $x=0$, the iteration might oscillate around it. In this case, we will need to look for the point where the subdifferential includes zero. This is the generalization of the familiar method of finding the minimum by looking for the zero-gradient point, only that the relation gradient=0 is replaced by $0 \in$ subdifferential. To be specific, a point $x^\ast$ is a minimizer of a function $f(x)$ (no necessarily convex) iff $f(x)$ is subdifferentiable at $x^\ast$ and

\[0 \in \partial f(x^\ast ),\]i.e. $0$ is a subgradient at $x^\ast$. Using this method it is easy to see that $x=0$ is indeed the minimizer of $\left\lvert x \right\rvert$.

Proximal gradient methods

Proximal gradient methods are a generalized form of projection used to solve non-differentiable convex optimization problems.

The function we want to minimize is a composite function

\[f(x) = g(x) + h(x),\]where $g(x)$ is supposed to be differentiable while $g(x)$ is not. For example, $h(x)$ could be the LASSO punish term $\left\lVert x \right\rVert_ {2}$. Since $h(x)$ is not differential, we can’t use the gradient descent method directly to $g+h$. However, we can use $g(x)$ to define the gradient method, then somehow include the effect of $h(x)$. The $g$-gradient descent iteration will decrease the value of $g(x)$, then we do something to also decrease the value of $h(x)$, thus the final result will decrease both $g(x)$ and $h(x)$. That’s the general idea of proximal gradient methods, we will explain the word proximal later.

Say we start with some intermediate value $x^{(k)}$. First let’s consider $g(x)$ only, and define the quadratic approximation function $\overline{g}^{(l)}(x)$ of $g(x)$ at $x^{(k)}$, that is we use a quadratic function $\overline{g}^{(k)}$ (which is concave) to approximate $g$ around $x^{(k)}$, $\overline{g}$ is constructed such that it is tangent to $g$ at $x^{(k)}$. Specifically,

\[\overline{g}^{(k)}(z) = g(x^{(k)}) + (z-x^{(k)}) \nabla g(x^{(k)}) + \frac{1}{2\alpha} (z-x^{(k)})^{2}.\]Gradient descent method using $g(x)$ alone will update it as

\[x^{(k+1)}_ {g} := \text{arg min}_ {z}\, \overline{g}^{(k)}(z) = x^{(k)} - \alpha \nabla g(x^{(k)}).\]This is the first step. In the next step, we take into consideration $h(x)$ function and minimize the so-called composite function, which is the sum of the quadratic approximation $\overline{g}$ and the non-differentiable function $h(x)$, the result would be $x^{(k+1)}$, the real $(k+1)$-th iteration:

\[x^{(k+1)} := \text{arg min}_ {z}\left\lbrace \overline{g}^{(k)}(z) + h(z) \right\rbrace .\]The logic is

\[x^{(k)} \to x^{(k+1)}_ {g} \to x^{(k+1)}.\]I hope it is intuitive. Now let’s try to solve it,

\[\begin{align*} x^{(k+1)} &:= \text{arg min}_ {z}\left\lbrace \overline{g}^{(k)}(z) + h(z) \right\rbrace \\ &= \text{arg min}_ {z}\left\lbrace g(x^{(k)}) + (z-x^{(k)}) \nabla g(x^{(k)}) + \frac{1}{2\alpha} (z-x^{(k)})^{2} + h(z) \right\rbrace \\ &= \text{arg min}_ {z}\left\lbrace \frac{1}{2\alpha}[z^{2}-2z(x^{(k)}-\alpha \nabla g)+2 \alpha (g- x^{(k)} \nabla g)] + h(z) \right\rbrace \\ &= \text{arg min}_ {z}\left\lbrace \frac{1}{2\alpha}([z-(x^{(k)}-\alpha\nabla g )]^{2} + C_ {1}) + h(z) \right\rbrace \\ &= \text{arg min}_ {z}\left\lbrace \frac{1}{2\alpha}[z-x^{(k+1)}_ {g}]^{2} + h(z) \right\rbrace, \end{align*}\]where in the fourth line we completed the square and in the last line we got rid of a constant term (independent of $z$) in $\text{arg min}$, since adding to a function a constant term does not change the minimizer of it.

Notice that the form of $x^{(k+1)}$ is very similar to the gradient descent method with step size $\alpha$. Regarding $x^{(k+1)}$ we are minimizing some function plus $\frac{1}{2\alpha}(z-x_ {g}^{(k)})^{2}$, while in the gradient descent method where we are minimizing some linear function plus $\frac{1}{2\alpha}(z-x^{k})^{2}$. This inspires us to look at $x^{(k+1)}$ with another perspective: we are trying to minimize $h(z)$, in the mean while trying to stay close to $x_ {g}^{(k+1)}$. In other words, we are looking for the minimizer of $h(z)$ which is also proximal to $x^{(k+1)}_ {g}$. Now it is a good time to introduce proximal operator $\text{prox}_ {h,\alpha}(x)$, which aims to find the minimizer of function $h$, with step length $\alpha$, proximal to $x$,

The proximal gradient method works as follows. Given the composite function $f=g+h$ where $g$ is differentiable and $h$ is not. We choose initial value $x^{(0)}$ of $x$, iterate it by repeating

where $\alpha^{(k)}$ is the $k$-th step length.

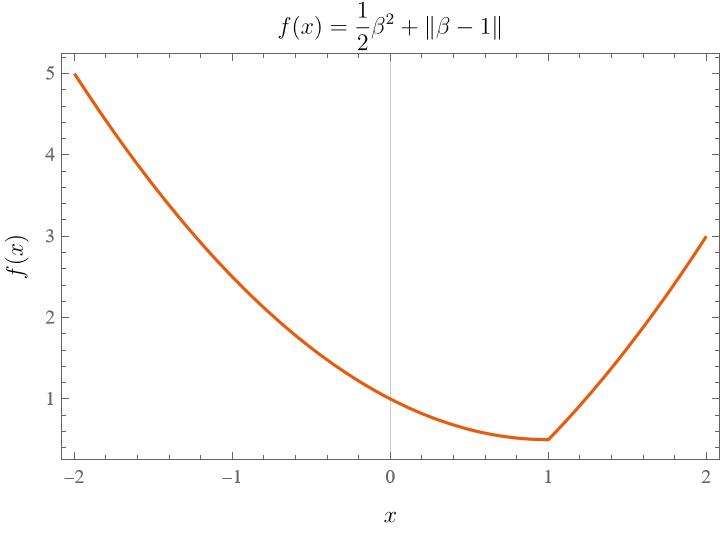

As an example, let’s start with a simple problem that we already know how to solve, apply the proximal gradient method and see how it works. Say we want to minimize a function $f(\beta)$ with only one variable $\beta$,

\[f(\beta) = \frac{1}{2} \beta^{2} + \left\lvert \beta-1 \right\rvert .\]The plot is given in the below.

The minimum is at $\beta=1$, as $0 \in \partial f(\beta){\Large\mid}_ {\beta=1}$. Now let’s try to use the proximal gradient method to solve it. Let us start with

\[\beta^{(0)} = 0,\]Use the gradient method with $h(x)=\frac{1}{2} \beta^{2}$ to update the result only, we get

\[\beta_ {h}^{(1)} = \beta^{0}-\alpha \nabla h(0) = \beta^{(0)} = 0,\]this is because $h(\beta)$ has zero derivative at $\beta=0$. Next we use proximal operator to update $\beta_ {h}^{(1)}$,

\[\begin{align*} \beta^{(1)} &= \text{prox}_ {\left\lvert \bullet-1 \right\rvert,\alpha }(\beta^{(1)}_ {g}) \\ &=\text{arg min}_ {z} \left\lbrace \frac{1}{2\alpha}(z-\beta^{(1)}_ {g})^{2}+\left\lvert z-1 \right\rvert \right\rbrace \\ &= \text{arg min}_ {z} \left\lbrace \frac{1}{2\alpha}z^{2}+\left\lvert z-1 \right\rvert \right\rbrace. \end{align*}\]Now we can use the sub-gradient method to find the minimum. The subgradient reads

\[\partial \left( \frac{1}{2\alpha}z^{2}+\left\lvert z-1 \right\rvert \right)= \begin{cases} \frac{z}{\alpha}+1 & z>1 \\ [ \frac{1}{\alpha}-1, \frac{1}{\alpha}+1] & z=1 \\ \frac{z}{\alpha}-1 & z<1 \end{cases}\]it is clear that for any $\alpha$ satisfying $\frac{1}{\alpha}-1<0$ and $\frac{1}{\alpha}+1>0$, zero subgradient is obtained at $z=1$. That is to say, for any $\alpha>0$m we gave

\[\beta^{(1)} =1\]which is precisely the result we are looking for. Along the way we have also found a constraint for the value of step size $\alpha$.

Another thing which might be useful is the so-called soft-thresholding operator, defined as:

where $\lambda$ is a non-negative threshold parameter, $\text{sign}(x)$ returns the sign of $x$, and $\max(\lvert x\rvert - \lambda, 0)$ essentially shrinks $x$ towards zero by $\lambda$, setting it to zero if $x$ is within $\lambda$ of zero.

To minimize this function using the soft-thresholding operator, we need to follow these steps:

\[S_ {\lambda}(\theta) = \text{sign}(\theta) \cdot \max(\left\lvert \theta \right\rvert - \lambda, 0)\]For future use, we need to find the Hessian of the loss function $J(\beta)$ from logistic regression, we need to compute the second-order partial derivatives of $J(\beta)$ with respect to the components of the parameter vector $\beta$. Given

\[J(\beta) := -\sum_ {i} \left[ y_ i t_ i - \ln(1 + e^{t_ i}) \right], \quad t_ i = \beta_ 0 + \beta \cdot X_ {(i)}.\]where

\[t_ i = \beta_ 0 + \sum_ {j=1}^{p} \beta_ j X_ {ij}\]and $\beta = (\beta_ 1, \beta_ 2, \ldots, \beta_ p)$, $X_ {(i)} = (X_ {i1}, X_ {i2}, \ldots, X_ {ip})$.

First, we compute the gradient of $J(\beta)$ with respect to $\beta_ 0$ and $\beta_ j$.

\[\frac{\partial J(\beta)}{\partial \beta_ 0} = -\sum_ {i} \left[ y_ i - \frac{e^{t_ i}}{1 + e^{t_ i}} \right].\]Let $p_ i = \frac{e^{t_ i}}{1 + e^{t_ i}} = \sigma(t_ i)$, the sigmoid function. Then,

\[\frac{\partial J(\beta)}{\partial \beta_ 0} = -\sum_ {i} \left[ y_ i - p_ i \right].\] \[\frac{\partial J(\beta)}{\partial \beta_ j} = -\sum_ {i} \left[ y_ i X_ {ij} - \frac{e^{t_ i}}{1 + e^{t_ i}} X_ {ij} \right].\]Using $p_ i = \sigma(t_ i)$, this becomes:

\[\frac{\partial J(\beta)}{\partial \beta_ j} = -\sum_ {i} \left[ y_ i X_ {ij} - p_ i X_ {ij} \right] = -\sum_ {i} X_ {ij} \left[ y_ i - p_ i \right].\]Now we compute the second-order partial derivatives to form the Hessian matrix.

Second partial derivative with respect to $\beta_ 0$:

\[\frac{\partial^2 J(\beta)}{\partial \beta_ 0^2} = -\sum_ {i} \left[ - \frac{\partial p_ i}{\partial t_ i} \frac{\partial t_ i}{\partial \beta_ 0} \right] = \sum_ {i} p_ i (1 - p_ i).\]Mixed partial derivative with respect to $\beta_ 0$ and $\beta_ j$:

\[\frac{\partial^2 J(\beta)}{\partial \beta_ 0 \partial \beta_ j} = -\sum_ {i} \left[ - \frac{\partial p_ i}{\partial t_ i} \frac{\partial t_ i}{\partial \beta_ j} \right] = \sum_ {i} p_ i (1 - p_ i) X_ {ij}.\]Second partial derivative with respect to $\beta_ j$ and $\beta_ k$:

\[\begin{align*} \frac{\partial^2 J(\beta)}{\partial \beta_ j \partial \beta_ k} &= -\sum_ {i} \left[ - \frac{\partial p_ i}{\partial t_ i} \frac{\partial t_ i}{\partial \beta_ j} \frac{\partial t_ i}{\partial \beta_ k} \right] = \sum_ {i} p_ i (1 - p_ i) X_ {ij} X_ {ik}\\ &= (X^{T} Q X)_ {jk} \end{align*}\]where $Q_ {mn} = \delta_ {mn}p_ {m}(1-p_ {m})$.

The full Hessian matrix $H$ is composed of these second-order partial derivatives. It can be written in block form as follows:

\[H = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial^2 J(\beta)}{\partial \beta_ 0^2} & \frac{\partial^2 J(\beta)}{\partial \beta_ 0 \partial \beta_ 1} & \cdots & \frac{\partial^2 J(\beta)}{\partial \beta_ 0 \partial \beta_ p} \\ \frac{\partial^2 J(\beta)}{\partial \beta_ 1 \partial \beta_ 0} & \frac{\partial^2 J(\beta)}{\partial \beta_ 1^2} & \cdots & \frac{\partial^2 J(\beta)}{\partial \beta_ 1 \partial \beta_ p} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ \frac{\partial^2 J(\beta)}{\partial \beta_ p \partial \beta_ 0} & \frac{\partial^2 J(\beta)}{\partial \beta_ p \partial \beta_ 1} & \cdots & \frac{\partial^2 J(\beta)}{\partial \beta_ p^2} \end{bmatrix}.\]Using the derived second-order partial derivatives, the Hessian matrix can be written as:

\[H = \sum_ {i} p_ i (1 - p_ i) \begin{bmatrix} 1 & X_ {i1} & X_ {i2} & \cdots & X_ {ip} \\ X_ {i1} & X_ {i1}^2 & X_ {i1}X_ {i2} & \cdots & X_ {i1}X_ {ip} \\ X_ {i2} & X_ {i2}X_ {i1} & X_ {i2}^2 & \cdots & X_ {i2}X_ {ip} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ X_ {ip} & X_ {ip}X_ {i1} & X_ {ip}X_ {i2} & \cdots & X_ {ip}^2 \end{bmatrix}.\]4.2 With Tsallis statistics

There exist tremendous potential in applying Tsallis entropy to biostatistics, mostly for two reasons:

- Tsallis statistics modifies logarithmic and exponential functions, and they are ubiquitous in logistic regression methods;

- Tsallis entropy can seamlessly generalize the familiar Shannon entropy, which is closely connected to the cross entropy loss function, which is exactly the loss functions we used in regression method.

As a starter, in this note we will only focus on the generalization of sigmoid function, keeping other components unchanged. But first, let’s repeat the definition for Tsallis-modified log and exponential functions, so-called $q$-log and $q$-exponentials, for future convenience:

\[\begin{align*} \log_ {q} (x) := & \frac{x^{1-q}-1}{1-q}, \\ \exp_ {q}(x) :=& (1+(1-q))^{1/(1-q)}. \end{align*}\]As you can check, at the limit $q\to 1$ they regress to normal log and exp functions.

q-sigmoid of the first kind

The regular sigmoid function reads

\[\sigma(z) = \frac{1}{1+e^{ -z }},\]we generalized it to $q$-sigmoid function:

\[\boxed{ \sigma_ {q}(z) := \frac{1}{1+\exp_ {q}(-z)}. }\]To ensure that the range is $[0,1]$ for all $q$, we might need to modified it a little bit, for example multiply by a constant or do some cut-off.

The $q$-sigmoid function satisfy the following relation:

\[\frac{ \partial \sigma_ {q}(z) }{ \partial z } = \beta(q,z)\sigma_ {q}(z)(1-\sigma_ {q}(z))\]where

\[\beta(q,z) = \frac{1}{1-z(1-q)}.\]This should be compared to the case of regular sigmoid function:

\[\frac{ \partial \sigma(z) }{ \partial z } = \sigma(z) (1-\sigma(z)).\]The cross entropy loss function now reads

\[\boxed{ L= - \sum_ {i=1}^{n}[y_ {i}\log(\sigma _ {q_ {i} }(z_ {i} ))+(1-y_ {i})\log(1-\sigma_ {q_ {i} }(z_ {i} ))]. }\]where $z_ {i}=\theta\cdot X^{(i)}$, $X^{(i)}$ the $i$-th observed data and the q-parameters $q_ {i}$ are different for each sample. Someone write it as $z_ {i}=\theta^{T}X^{(i)}$, but I neglect the transpose symbol since now both $\theta$ and $X$ are understood as vectors. For starters we can set all the $q_ {i}$ as the same constant for all samples, varying about $1$, for example from -0.2 to 1.8 or something. This will greatly reduce the number of free parameters hence prevents over fitting.

We will use the gradient method to find the optimal values of parameters that minimized the loss function. Next we work out the derivative of loss function.

Some straightforward derivation shows that

\[\frac{ \partial L(y,\sigma_ {q}(z)) }{ \partial z } = \beta_ {q}(z)(\sigma_ {q}(z)-y),\]where $\beta_ {q}(z) = \frac{1}{1-z(1-q)}$. The derivative of the loss function with respect to parameters can be readily written as

\[\boxed{ \frac{ \partial L(y,\theta) }{ \partial \theta ^{a} } = \sum_ {i} \beta_ {q}(z) (\sigma_ {q}(z_ {i} )-y_ {i})X^{(i)}_ {a}, \quad z_ {i} =\sum_ {a}\theta^{a} \cdot X^{(i)}_ {a} = \theta \cdot X^{(i)}. }\]Note that I have replace $q_ {i}$ with an universal $q$. In contrast to the classical result, there is an extra $\beta$ factor which is nonlinear in both $q$ and $z$.

After we plugin this result to gradient method, $\beta(q,z)$ will play a similar rule as $\alpha$, hence in a sense, using $q$-sigmoid naturally introduce the learning rate! We can even set $\alpha=1$ and get

\[\hat{\theta}_ {(t)} = \hat{\theta}^{(t-1)} -\beta(q,z)(\sigma_ {q}(z)-y).\]The learning rate $\alpha$ can be chosen according to the Lipschitz constant $L$ as

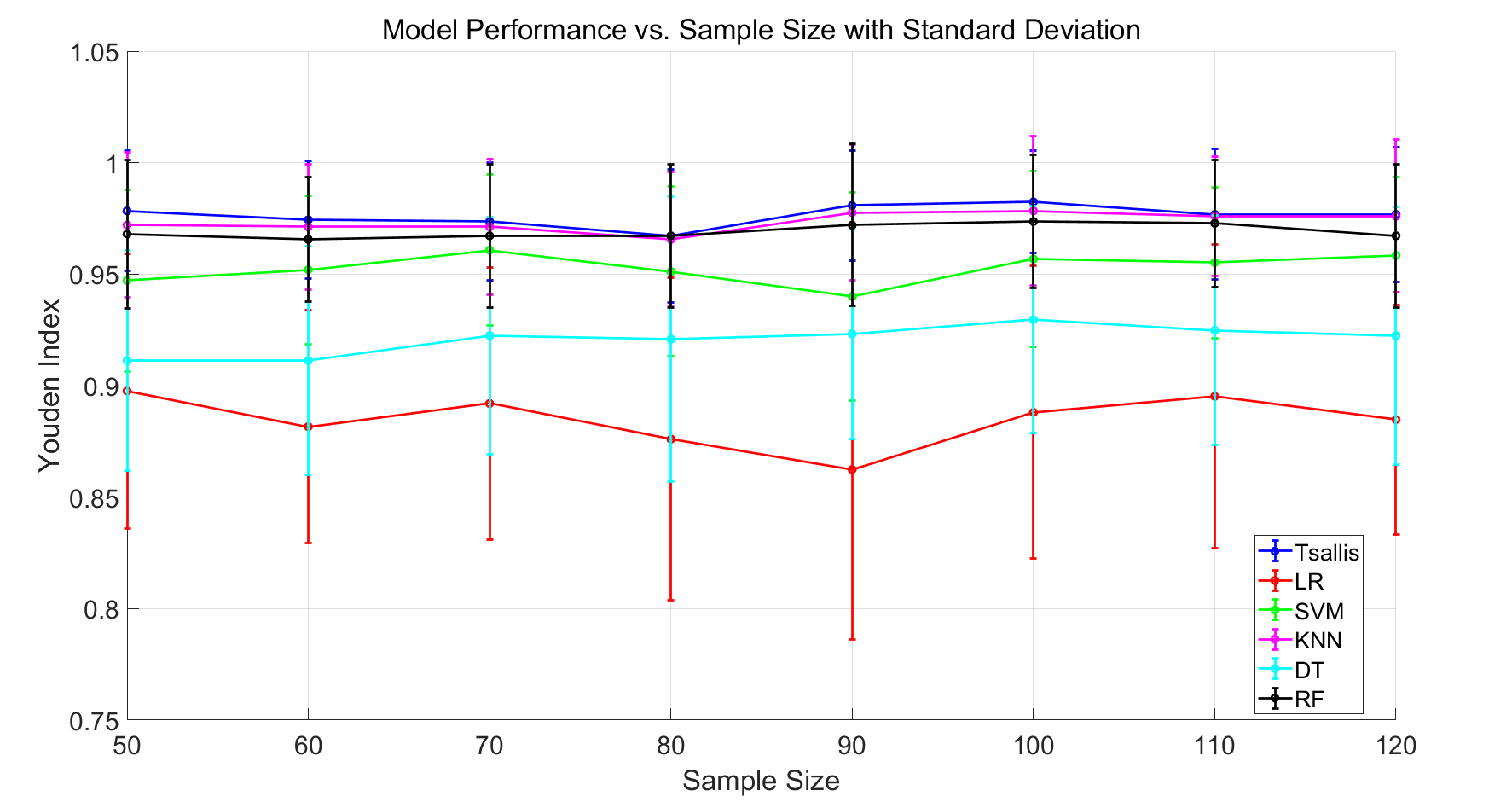

\[\alpha = \frac{1}{L}.\]Some preliminary results are Obtained and put in the following figure.

q-sigmoid of the second kind

Another equivalent expression for the standard sigmoid function reads

\[\sigma(z) = \frac{e^{ z }}{e^{ z }+1},\]substitute in the q-exponent function, we have the second kind of q-sigmoid function:

\[\overline{\sigma}_ {q}(z) := \frac{\exp_ {q}(z)}{\exp_ {q}+1}.\]This is inequivalent to the q-sigmoid of the first kind since q-exponent satisfy

\[\exp_ {q}(z)\exp_ {q}(-z) = \exp_ {q}((1-q)z^{2}) \neq 1.\]The second kind of q-sigmoid can be obtained in another way. The original logistic regression method works like the following: let $p(1\mid z)$ be the measured (real) probability for outcome $1$ and $\hat{p}(1\mid z)$ for the theoretical prediction. The logit function is the bridge between the microscopic information represented by $z$, and the predicted macroscopic measure result $\hat{p}(1\mid z)$, in a linear fashion:

\[\text{logit}(\hat{p}) = \log\left( \frac{\hat{p}}{1-\hat{p}} \right)=z.\]We can directly generalize it to $q$-logit function by replacing the log with q-log,

\[\text{logit}_ {q}(\hat{p}) := \log_ {q}\left( \frac{\hat{p}}{1-\hat{p}} \right)=z.\]Invert the relation we have

\[\hat{p}(1\mid z) := \frac{\exp_ {q}(z)}{\exp_ {q}(z)+1},\]which is the q-sigmoid function of the second kind.

We have

\[\frac{d}{dz} \overline{\sigma}_ {q}(z) = \overline{\sigma}_ {q} (z)(1-\overline{\sigma}_ {q} (z))\beta _ {q} (-z), \quad \beta _ {q} (-z)=\frac{1}{1+(1-q)z}.\]Note the difference from the q-sigmoid of the first kind, where in the derivative, we have $\beta _ {q}(z)$ instead.

The derivative of cross-entropy loss function with respect to the parameters reads

\[\boxed{ \frac{ \partial L }{ \partial \theta_ {a} } =\sum_ {i=1}^{n} [\overline{\sigma}_ {q} (z_ {i} )-y_ {i}] \beta _ {q} (-z_ {i} )X^{(i)}_ {a}, \quad z_ {i} =\sum_ {a}\theta_ {a}X^{(i)}_ {a}= \vec{\theta}\cdot \vec{X}^{(i)}. }\]Future work:

- Parametar gradation. The hierachy of parameters. Tsallis parameter depends on Higher-level parameters;

- A range of q-value goes into the Boltzmann statistics.

- Renormalization in higher dimensional data.

Appendix. Useful Mathematical Formulae

The definition of $q$-logarithm and $q$-exponential, $x>0, q \in\mathbb{R}$:

\[\begin{align*} \ln_ {q}x &:= \frac{x^{1-q}-1}{1-q}, \\ e^{ x }_ {q} &:= (1+(1-q)x)^{1/(1-q)},\quad 0 \text{ if } 1+(1-q)x<0. \end{align*}\]Note that in the definition of the exponential it is required that $1+(1-q)x>0$, otherwise it is defined to be zero. This is to make sure the the value of $e_ {q}$ is positive definite. It is easily checked that $\log q$ and $\exp {q}$ are indeed inverse to each other.

many formula for $q$-logarithms reminds us of that for the regular $q$-logarithms.

\[\begin{align*} \ln_ {q}(xy) &= \ln_ {q}(x)+ \ln_ {q}(y) + (1-q)\ln_ {q}(x)\ln_ {q}(x) , \\ \ln_ {q}(1+x) &= \sum_ {1}^{\infty} (-1)^{n-1} \frac{(q)_ {n}}{n!} x^{n}, \\ (q)_ {n} &= \frac{\Gamma(q+k)}{\Gamma(q)} = q(q+1)\cdots(q+k-1), \\ \ln_ {q}\prod_ {k=1}^{n}x_ {k} &= \sum_ {k=1}^{n} (1-q)^{k-1}\sum_ {i_ {k} >\cdots>i_ {1}=1}^{n} \ln_ {q}x_ {i_ {1}}\cdots\ln_ {q}x_ {i_ {k}}. \end{align*}\]We also have

\[\begin{align*} \ln_ {q} x &= x^{1-q}\ln_ {2-q}x , \\ q \ln_ {1-q}x^{a} &= a \ln_ {1-a} x^{q} . \end{align*}\]Regarding the $q$-exponentials,

\[\begin{align*} \left( e_ {q}^{f(x)} \right) ^{a} &= e^{ af(x) }_ {1-(1-q)/a},\\ \frac{d}{dx} e_ {q}^{f(x)} &= (e_ {q}^{f(x)})^{q} \times f'(x) \end{align*}\]For more details, refer to the textbook by Tsallis himself and https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4371(01)00567-2.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: