Yoneda Lemma

Table of Contents

1. Representables

A category is a world of objects, all looking at one another. Each sees the world from a different viewpoint. Take the category of topological spaces for example, consider the object with only one point, denoted $\star$, given another topological space $T$, a map

\[\star\to T\]can be regarded as $\star$ looking at $T$. What does $\star$ see? Since $\star$ itself is a point, the image given by a continuous map (by definitions the morphisms in the category of topological spaces are continuous maps) of $\star$ is another point in $T$, that’s to say, a point can only see other points! $\star$ can’t see any other structures, limited by its nature. This is similar to what happens in a society, with real people in it as objects. A curve, on the other hand, could see much more. It can see a point if it wants (a constant map), but it can also see another curve in other objects. In the language of category theory, $A$ seeing $B$ means a map from $A$ to $B$, and all the perspectives an from $A$ of $B$ translates into the set of arrows $\mathcal{M}(A,B)$.

We can also ask the dual question: fixing an object in a category, what the set of all the maps into it? Take the category $\text{Set}$ of sets for example. Consider a set with only two elements. Given any set $X$, the maps from $X$ to the two element set is the subset of $X$.

In the following we will talk about how each object sees and is seen by the category. This naturally leads to the notion of representable functors, or just representables.

Fix an object $A \in \mathcal{A}$. Consider the totality of maps out of $A$. To each $B\in \mathcal{A}$, there is assigned the set $\mathcal{A}(A,B)$ of maps from $A$ to $B$. This assignation is actually functorial, in the sense that to each $B\in\mathcal{A}$, there is a set $A(A,B)$, and to each arrow in $A$, there is another arrow in the codomain of this functor, which we will define shortly.

Definition 1. Let $\mathcal{A}$ be a locally small (meaning that the arrows from any object to any another actually form a set) category and $A\in \mathcal{A}$. Define a functor

\[H^{A}: B \mapsto \mathcal{A}(A,B)\]where $\mathcal{A}(A,B)$ are the collection of arrows from $A$ to $B$, here $\mathcal{A}(A,B)$ is regarded as a set. Thus

\[H^{A}: \mathcal{A}\to \text{Set}\]where $\text{Set}$ is the category of sets, the objects of which are sets and the arrows are functions from one set to another. Obviously $H^{A}$ is a set-valued functor defined on $\mathcal{A}$. For $A’ \in \mathcal{A}$,

\[H^{A}(A') := \mathcal{A}(A \to A') \text{ regarded as a set}.\]An easy way to remember the direction of arrows is to think of $A$ in $H^{A}$ as standing high above its peers, since it appears in superscript, it is standing “upstairs”, as a result $A$ has a pretty good view, enabling it to “see” other objects in $\mathcal{A}$, and the arrow $A \to B$ represents that $A$ is watching $B$. With this analogy, the big brother is watching everyone in the nation, this makes the big brother the initial object. Similarly, given $A \in \mathcal{A}$, when we need to talk about arrow coming from other objects into $A$, we will define the functor $H_ {A}$ where $H_ {A}(B)$ is the set of arrows from $B$ to $A$ this time, for $A$ sits at the bottom and everyone can see $A$.

For a map $g: A’ \to A’’$ in $\mathcal{A}$, $H^{A}$ maps $g$ to another map from $H^{A}(A’)$ to $H^{A}(A’’)$ by composition, that is

\[H^{A}(A'): A \to A', \quad H^{A}(A'') : A\to A'', \quad H^{A}(g): (A\to A') \to (A\to A'')\]where $H^{A}(g)$ is realized by

\[A\to A' \xrightarrow{g} A''\]which is a map from $A$ to $A’’$, hence an element of $H^{A}(A’’)$.

To explain it in a different way, consider an element $X\in H^{A}(A’)$, $X$ by construction is a map from $A$ to $A’$. Let $Y \in H^{A}(A’’)$, then $Y$ is nothing but a map from $A$ to $A’’$. Now, what is an arrow from $X$ to $Y$? It is something that maps $A\to A’$ to $A \to A’’$, which can be achieved by the composition $g\,\circ\,X$, where $g: A’ \to A’’$.

Sometimes $H^{A}(g)$ is written as $g\,\circ\,-$, where $-$ is a place holder; or written as $g_ {\ast}$, reminding us that it is somehow “induced” by $g$. All are frequently used in publications.

Again, let $A$ be a locally small category. A functor

\[X: \mathcal{A} \to \text{Set}\]is representable if

$A$ is said to be a representation of $X$, together with an isomorphism between $H^{A}$ and $X$. In other words, when dealing with a representable functor $X$, identifying a representation for $X$ requires more than just specifying an object $A$; we must also precisely determine how $X$ is isomorphic to $H^A$.

Representable functors are sometimes just called representables. Only set-valued functors (functors with codomain $\text{Set}$) can be representable.

Representable functors are important for a few reasons. They are important for understanding the Yoneda lemma, which is the topic of this note and arguable the most profound lemma in category theory. We will introduce the Yoneda lemma shortly, roughly speaking it states that every functor is naturally isomorphic to a functor represented by some object in the category. This lemma provides a powerful tool for embedding any locally small category into a category of functors (where the arrows are natural transformations). The Yoneda embedding, which arises from this, embeds a category into a category of presheaves, preserving and reflecting properties of objects and morphisms. If you don’t know (or not interested in) what a presheave is, just ignore it.

Furthermore, representable functors are key in the study of natural transformations. The naturality condition can be better understood and characterized using representables. Representables also play a role in the study of adjoints and limits. For instance, adjoint functors can often be characterized using representables, and the existence of certain limits and colimits (limits where all the arrows are reversed) can be analyzed through representable functors. Representables are also indispensable to sheaf theory and topos theory, providing a link between geometric intuition and abstract category-theoretic formalism. Unfortunately these fascinating results lie beyond the scope of this simple note.

Since we are already talking about the category of functors, it is perhaps a good time to mention two similar but distinct definitions in category theory, namely the category of functors and the so-called $2$-category.

-

Category of Functors: This is a construction where the objects are functors and the morphisms between these objects are natural transformations. Specifically, given two categories $\mathcal{C}$ and $\mathcal{D}$, the category of functors, often denoted $\text{Fun}(\mathcal{C}, \mathcal{D})$ or just $[\mathcal{C},\mathcal{D}]$, has as objects all functors from $\mathcal{C}$ to $\mathcal{D}$ and as morphisms the natural transformations between these functors.

-

$2$-Category: A $2$-category is a more general and abstract concept. In a $2$-category, there are objects, morphisms between objects (also called

1-morphisms), and morphisms between morphisms (called2-morphisms), or “arrows between arrows”. This structure introduces a new level of morphisms.

In a certain sense, the category of functors between two categories can be seen as a specific example of a 2-category, where the objects are the categories, the 1-morphisms are the functors between these categories, and the 2-morphisms are the natural transformations between these functors. However, the concept of a 2-category is broader and can be applied to many other contexts beyond just categories and functors.

Example.1 Consider the category of sets, denoted $\text{Set}$, let $1$ be the set of only one element. Now, what would $H^{1}$ be? It can be written as

\[\text{Mor}(1,-) \text{ or } \text{Hom}(1,-) \text{ or } \text{Set}(1,-),\]they all mean the same thing: the maps from $1$ to something else. Let $S \in Set$, $H^{1}(S)$ would be the collection of the maps from $1$ to $S$, which is itself another set, hence

\[H^{1}: \text{Set} \to \text{Set}.\]Since a map from $1$ to a set $S$ amounts to an element of $S$, we have

\[H^{1}(S) \cong S \quad \;\forall\; S \in \text{Set}.\]It can be shown (which I will not do here) that this isomorphism is natural in $S$, so $H^{1}$ is naturally isomorphic to the identity functor $\mathbb{1}_ {\text{Set}}$. Hence $\mathbb{1}_ {\text{Set}}$ is representable, by $1$.

Representability is not a property shared by just any set-valued functor. In fact, rather few functors are representable, consider the total amount of functors we could construct. However, forgetful functors tend to be representable. We state without proof the following proposition.

Proposition. Any set-valued functor with a left adjoint is representable.

We have defined, for each object $A$ of category $\mathcal{A}$ , a functor $H^{A}\in[\mathcal{A},\text{Set}]$ (given two categories $\mathcal{A}$ and $\mathcal{B}$, $[\mathcal{A},\mathcal{B}]$ is the functor category from the former to the latter). This describes how $A$ sees the world. As $A$ varies, so does its view of the world. On the other hand, it is always the same world being seen, so the different views from different objects are somehow related. Generally speaking, whenever there is a map between objects $A$ and $A’$, there is also an induced map between $H^{A}$ and $H^{A’}$. Since $H^{A}$ are $H^{A’}$ are both functors (the “view” of $A,A’$), a map between them are possibly natural transformation. It is only a possibility since we still have to show that it satisfies naturality condition.

To be precisely, a map

\[f: A' \to A,\quad A,A'\in \mathcal{A}\]induces a natural transformation

\[H^{f} : H^{A} \to H^{A'}.\]An interactive diagram of this can be found here.

Recall that a natural transformation $\alpha$ between two functors $F$ and $G$, both from category $\mathcal{C}$ to category $\mathcal{D}$, consists of components. Each component is a morphism in category $\mathcal{D}$. Namely, for each object $X$ in category $\mathcal{C}$, the component of the natural transformation $\alpha$ at $X$ is a morphism in category $\mathcal{D}$:

These components must satisfy a naturality condition, which states that for every morphism $f: X \rightarrow Y$ in category $\mathcal{C}$, the naturality diagram commutes. The naturality condition must hold for all objects and morphisms in category $C$, making the transformation “natural” in the sense that it works consistently across the entire category.

Coming back to $H^{f}$. Let $B\in \mathcal{A}$, what is the $B$-component $H^{f}_ {B}$ of $H^{f}$? Recall that $f$ maps $A’$ to $A$, by construction $H^{f}$ maps in the opposite direction, it is the function

\[H^{A}(B) \equiv \mathcal{A}(A,B) \to H^{A'}(B)\equiv \mathcal{A}(A',B),\]in terms of the elements, let $p \in \mathcal{A}(A,B)$ we have

\[H^{f}: p \mapsto p\,\circ\,f.\]Definition. Let $\mathcal{A}$ be a locally small category, the functor

\[H^{-}: \mathcal{A}^{\text{op}} \to [\mathcal{A},\text{Set}]\]is defined on objects such as $A$ by $H^{-}(A)=H^{A}$, and on maps such as $f$ by $H^{-}(f)=H^{f}$.

Some explanation is in order. The dash $-$ in $H^{-}$ is a placeholder, to be filled with whatever it acts on, may it be an object or an arrow. $\mathcal{A}^{\text{op}}$ is the opposite, or dual category of $\mathcal{A}$, with same objects but reversed arrows (all of them). $\mathcal{A}^{\text{op}}$ is a category, $[\mathcal{A},\text{Set}]$ is another category ( of functors from $\mathcal{A}$ to $\text{Set}$), thus $H^{-}$ is a map from one category to another, thus a functor. $H^{-}$ of $A$ is $H^{A}$, which is a set-valued functor on $\mathcal{A}$, hence $H^{A}$ is an object of $[\mathcal{A},\text{Set}]$.

All of the definitions presented so far in this chapter can be dualized. At the formal level, this is trivial: just reverse all the arrows! But speaking with our analogy, after dualizing it, we are no longer asking what objects see, but how they are seen:

Let $\mathcal{A}$ be a locally small category and $A\in \mathcal{A}$. We define a functor $H_ {A}$ as follows,

\[H_ {A} := \mathcal{A}(-,A): \mathcal{A}^{\text{op}}\to\text{Set}\]where

- for objects $B \in \mathcal{A}$, put $H_ {A}(B) = \mathcal{A}(B,A)$;

- For maps $g:B’\to B$, define

by

\[p\mapsto p\,\circ\,g \quad \;\forall\; p: B\to A.\]Note that a map $B’\to B$ induces a map in the opposite direction, $H_ {A}(B)\to H_ {A}(B’)$.

We now define representability for contravariant set-valued functors.

Let $\mathcal{A}$ be a locally small category, and $X$ be a set-valued contravariant functor,

\[X: \mathcal{A}^{\text{op}} \to \text{Set}.\]We say $X$ is representable is $X \cong H_ {A}$ for some $A\in \mathcal{A}$. A representation of $X$ is a choice of $A$ and an isomorphism between $X$ and $H_ {A}$.

As an example, take the power set (contravariant-)functor $\mathcal{P}$ for example. Recall that the power set $\mathcal{P}(S)$ of a set $S$ is the collection of subsets of $S$. Let $S,S’\in \text{Set}$ be two sets, and $f: S \to S’$ a map (morphism) in the category of sets. Since we are regarding $\mathcal{P}$ as a contravariant functor, we should define $\mathcal{P}(f)$, which is a map from $\mathcal{P}(S’)$ to $\mathcal{P}(S)$, notice the reversed direction. Well, turns out this can be done in a more or less direct way: we define $\mathcal{P}(f)$ to be in a sense the inverse of $f$! Take $U\in\mathcal{P}(S’)$, we define the action on $U$ by $\mathcal{P}(f)$ by $f^{-1}(U)$, where $f^{-1}$ is not the inverse of $f$, for we didn’t assume that $f$ is invertible at all, but rather the preimage of $f$,

\[f^{-1} (U) := \left\lbrace s\in S \,\middle\vert\, f(s)\in U \right\rbrace .\]On the other hand, the subsets of $S$ can be regarded as a maps from $S$ to $2$, the set with two elements, which we call true and false. To see how it works, take $S=\left\lbrace 1,2 ,3\right\rbrace$, the subset $\left\lbrace 1,2 \right\rbrace$ can be regarded as a map $g: S\to \left\lbrace \text{true,false} \right\rbrace$ where $1,2$ are map to true and $3$ is mapped to false. Such maps are sometimes called the characteristic functions. This provides as another way to look at power sets, and confirms the idea that in category theory everything is a morphism!

Note that $\chi:=\left\lbrace \text{true,false} \right\rbrace$ is itself an object in $\text{Set}$, so we can talk about the Hom-functor $H_ {\chi}$, defined by maps from other stuff into $\chi$. Maybe not too surprisingly, $H_ {\chi}$ is isomorphic to the power functor $\mathcal{P}$,

\[\mathcal{P} \cong H_ {\chi}.\]Try to convince yourself with it, better with some simple examples. Thus we say the power functor $\mathcal{P}$ is representable, and the representation is $\chi$.

Just as we assembled the covariant representables $H^{A}$’s into a big functor $H^{-}$, we can do the same for the contravariant representables $H_ {A}$. If $f: A \to A’$ is a map in $\mathcal{A}$, there is an induced natural transformation $H_ {f}$:

\[H_ {f}: H_ {A} \to H_ {A'},\quad H_ {A},H_ {A'}: \mathcal{A}\to\text{Set}.\]Let $\mathcal{A}$ be a locally small category. The Yoneda embedding of $\mathcal{A}$ is the functor

defined on objects $A \in \mathcal{A}$ as $H_ {-}(A)=H_ {A}$ and arrows $H_ {-}(f)=H_ {f}$.

Note that in $[\mathcal{A}^{\text{op}},\text{Set}]$, the objects are functors from $\mathcal{A}^{\text{op}}$ to $\text{Set}$ and the arrows are natural transformations.

The Yoneda embedding provides a way to represent objects in a category as sets of morphisms (arrows) from other objects in the category to them. For each object $A\in\mathcal{A}$, the Yoneda embedding assigns a functor $H_ {A}$, it is sometimes called the Yoneda functor. In a sense, the Yoneda embedding allows as to regard each $A$ as arrows. Or, more precisely, it allows us to represent each $A$ as a set-valued functor. Yoneda embedding is a one-to-one correspondence between objects in $\mathcal{A}$ and functors in $[\mathcal{A},\text{Set}]$. In a sense to be explained, $H_ {-}$ embeds $\mathcal{A}$ into $[\mathcal{A},\text{Set}]$.

Let $\mathcal{A}$ be a locally small category, the functor

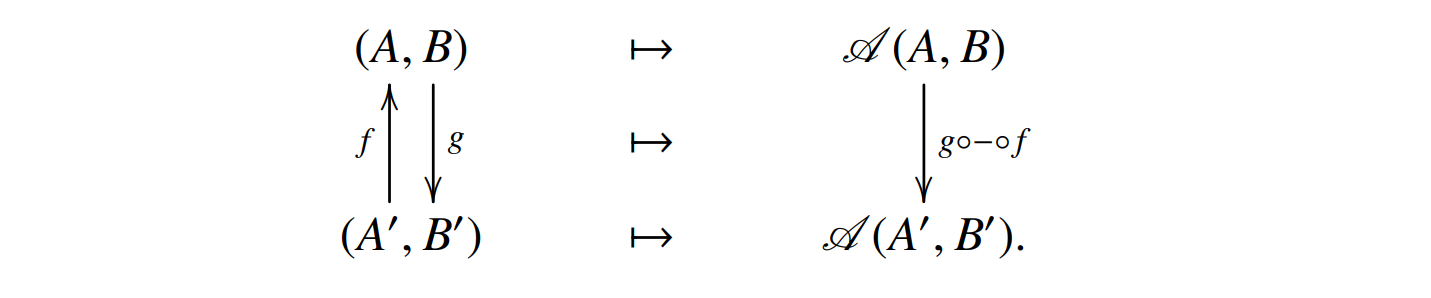

\[\text{Hom}_ {\mathcal{A}}: \mathcal{A}^{\text{op}}\times \mathcal{A}\to\text{Set}\]is defined by the following diagram,

This is like a generalization of $\text{Hom}(A,B)$ that we have encountered before. Recall that $\text{Hom}(A,B)$ is the set of the morphisms from $A$ to $B$, now $\text{Hom}_ {\mathcal{A}}$ is generalized such that it can also take two maps $f,g$ as well.

Given an arbitrary object in an arbitrary category, it is in general meaningless to talk about the “element” of this object since it not necessarily a set. However, in the category of sets, an element is the same thing as a map $1\to A$. This inspires the following definition.

Let $A$ be a locally small category. A Generalized element of $A$ is a map with codomain $A$. A map $S\to A$ is a generalized element of $A$ of shape $S$.

For example, a generalized element of a set $S$ of shape $\mathbb{N}$ is nothing but a sequence in $S$. In the category of topological spaces, the generalized elements of shape $1$ (the one point space) are points, and the generalized elements of shape $\mathbb{S}^{1}$ are loops.

Theorem.

If $H_ A \cong H_ {A’}$ where $A, A’$ are objects of a category $\mathcal{A}$ and $H_ A$ is the Yoneda embedding, then $A \cong A’$.

Proof.

To prove this theorem, we need to show that if the Yoneda embeddings $H_ A$ and $H_ {A’}$ are isomorphic as functors, then the objects $A$ and $A’$ must be isomorphic in the category $\mathcal{A}$.

Recall that the Yoneda embedding $H_ A$ is defined as the functor:

\[H_ A = \text{Hom}_ {\mathcal{A}}(-, A)\]Similarly,

\[H_ {A'} = \text{Hom}_ {\mathcal{A}}(-, A')\]Given $H_ A \cong H_ {A’}$, there exists a natural isomorphism $\eta: H_ A \to H_ {A’}$. This means for each object $X$ in $\mathcal{A}$, there is an isomorphism $\eta_ X: \text{Hom}_ {\mathcal{A}}(X, A) \to \text{Hom}_ {\mathcal{A}}(X, A’)$ that is natural in $X$.

We need to show there exists an isomorphism $f: A \to A’$ in $\mathcal{A}$.

Consider the identity morphism $\text{id}_ A \in \text{Hom}_ {\mathcal{A}}(A, A)$. The natural isomorphism $\eta$ gives us an isomorphism:

\[\eta_ A: \text{Hom}_ {\mathcal{A}}(A, A) \to \text{Hom}_ {\mathcal{A}}(A, A')\]Applying $\eta_ A$ to $\text{id}_ A$, we get a morphism $f \in \text{Hom}_ {\mathcal{A}}(A, A’)$:

\[f = \eta_ A(\text{id}_ A)\]Since $\eta$ is a natural isomorphism, there exists an inverse natural transformation $\eta^{-1}$ such that $\eta^{-1} \eta = \text{id}$.

Applying $\eta^{-1}_ {A’}$ to the identity morphism $\text{id}_ {A’} \in \text{Hom}_ {\mathcal{A}}(A’, A’)$, we get:

\[g = \eta^{-1}_ {A'}(\text{id}_ {A'}) \in \text{Hom}_ {\mathcal{A}}(A', A)\]We now have morphisms $f: A \to A’$ and $g: A’ \to A$. We need to show that these morphisms are inverses of each other.

Consider $f \circ g \in \text{Hom}_ {\mathcal{A}}(A’, A’)$. Since $\eta$ is a natural isomorphism, we have:

\[\eta_ {A'}(g) = \eta_ {A'}(\eta^{-1}_ {A'}(\text{id}_ {A'})) = \text{id}_ {A'}\]Thus, $f \circ g = \text{id}_ {A’}$.

Similarly, consider $g \circ f \in \text{Hom}_ {\mathcal{A}}(A, A)$. By the natural isomorphism $\eta$, we have:

\[\eta_ A(g \circ f) = \eta_ A(\eta_ A^{-1}(\text{id}_ {A})) = \text{id}_ A .\]Thus, $g \circ f = \text{id}_ A$.

Since $f \circ g = \text{id}_ {A’}$ and $g \circ f = \text{id}_ A$, it follows that $f$ and $g$ are indeed inverses of each other. Therefore, $f: A \to A’$ is an isomorphism in $\mathcal{A}$.

If the above proof is too abstract for you, it is always a good idea to come up with a simple example through which to see in real time how the logic works. In this case, a good example is to consider the category $\text{Set}$ of sets and let $A=\left\lbrace 1,2 \right\rbrace$, $A’=\left\lbrace a,b \right\rbrace$.

2. Yoneda Lemma

Let $\mathcal{A}$ be a locally small category so that the arrows from one object to another actually form a set. Let $X$ be a set-valued contravariant functor $X: \mathcal{A}^{\text{op}}\to\text{Set}$, let $H_ {A}$ be the Yoneda embedding, that is $H_ {A}(B)$ for all $B\in\mathcal{A}$ is the set of the arrows $\mathcal{A}[B,A]$. Now we have two distinct contravariant functor, the question is, what is the nature of the set of arrows from $H_ {A}$ to $X$? Recall that functors $\mathcal{A}^{\text{op}}\to\text{Set}$ is a presheaf, pre- in the sense that we haven’t talked about how can they be glued together to form a global sheaf. We can rephrase the question: for each $A\in\mathcal{A}$ we have a representable presheaf $H_ {A}$, if $X$ is another presheaf, what are the maps $H_ {A}\to X$?

Since $H_ {A}$ and $X$ are both objects of the presheaf category $\text{PSh}:=[\mathcal{A}^{\text{op}},\text{Set}]$, the maps from $H_ {A}$ to $X$ are maps in $\text{PSh}$. Since $H_ {A}$ and $X$ are also functors, a map between them is a natural transformation, denoted $\text{Hom}(H_ {A},X)$.

There is an informal principle of general category theory that allows us to guess the answer. In category theory, many conditions are indeed designed to ensure that different ways of composing arrows yield essentially the same result. This concept is central to the coherence conditions that appear in various categorical structures. Now, given all the ingredients, that is a locally small category $\mathcal{A}$, any element $A\in\mathcal{A}$, two presheaves $H_ {A}$ and $X$, we can construct two sets:

- $\text{Hom}(H_ {A},X)$, the set of the natural transformations from $H_ {A}$ to $X$ and,

- $X(A)$, the value of $A$ acted by $X$.

The informal principle suggests that these two sets are the same:

\[\text{Hom}(H_ {A},X) \cong X(A).\]This should hold for all $A\in\mathcal{A}$ and $X\in \text{PSh}$.

This is the informal statement of the Yoneda lemma. The formal statement is the following.

The Yoneda Lemma. For any functor $X: \mathcal{A}^{\text{op}} \to \text{Set}$ and any object $A$ in $\mathcal{A}$, there is a natural isomorphism:

\[\text{Hom}(H_ A, X) \cong X(A),\]where $\text{Hom}(H_ A, X)$ is the set of natural transformations from $H_ A$ to $X$.

A few comments. The set $\text{Hom}(H_ A, X)$ consists of all ways you can map the functor $H_ A$ to $X$ while respecting the structure of the category. The isomorphism $\text{Hom}(H_ A, X) \cong X(A)$ means that understanding these natural transformations is equivalent to simply looking at the set $X(A)$.

Think of $H_ A$ as a way to “probe” the structure of the category $\mathcal{A}$ using the object $A$. The Yoneda Lemma tells us that instead of looking at all possible ways to probe the category (which could be complicated), we can focus on the specific set $X(A)$, which contains all the information we need about the functor $X$.

Now it would be helpful to look at a concrete example. Let’s use the category of sets, $\text{Set}$, and consider the set $A = \left\lbrace 1,2 \right\rbrace$. We’ll use the power set functor $P$, which maps each set to its power set (the set of all its subsets) and each function to the corresponding image function. For a set $B$, the Yoneda embedding $H_ A$ is defined as:

\[H_ A(B) = \text{Set}(B, A).\]This is the set of all functions from $B$ to $A$.

For the functor $P: \text{Set}^{\text{op}} \to \text{Set}$ and the set $A$, the Yoneda Lemma states that there is a natural isomorphism:

\[\text{Hom}(H_ A, P) \cong P(A).\]Let’s apply Yoneda lemma. The Yoneda Embedding $H_ A$ reads

\[H_ A(B) = \text{Set}(B, \left\lbrace 1,2 \right\rbrace).\]For any set $B$, this is the set of all functions from $B$ to $\left\lbrace 1,2 \right\rbrace$. The power set functor $P$ acting on $B$ reads

\[P(B) = \left\lbrace \text{Subsets of } B \right\rbrace .\]For example, if $B = \left\lbrace a,b \right\rbrace$, then $P(B) = \left\lbrace \emptyset ,\left\lbrace a \right\rbrace ,\left\lbrace b \right\rbrace ,\left\lbrace a,b \right\rbrace \right\rbrace$. A natural transformation $\eta: H_ A \rightarrow P$ assigns to each set $B$ a function $\eta_ B: H_ A(B) \to P(B)$, satisfying a naturality condition.

Let’s use $B = \left\lbrace a,b \right\rbrace$ and see how a natural transformation works in practice. The Yoneda Embedding $H_ A(B)$ reads

\[H_ A(\left\lbrace a,b \right\rbrace) = \text{Set}(\left\lbrace a,b \right\rbrace, \left\lbrace 1,2 \right\rbrace),\]this is the set of all functions from $\left\lbrace a,b \right\rbrace$ to $\left\lbrace 1,2 \right\rbrace$. There are $2^2 = 4$ such functions:

\[f_ 1(a) = 1, f_ 1(b) = 1; \quad f_ 2(a) = 1, f_ 2(b) = 2; \quad f_ 3(a) = 2, f_ 3(b) = 1; \quad f_ 4(a) = 2, f_ 4(b) = 2.\]The power set functor $P(\left\lbrace a,b \right\rbrace)$ is

\[P(\left\lbrace a,b \right\rbrace) = \left\lbrace \emptyset ,\left\lbrace a \right\rbrace ,\left\lbrace b \right\rbrace ,\left\lbrace a,b \right\rbrace \right\rbrace.\]A natural transformation $\eta$ would map each function in $H_ A(B)$ to a subset of $B$.

Let’s define $\eta$ by mapping each function to the subset of $B$ where the function value is 1:

\[\eta_ {\left\lbrace a,b \right\rbrace}(f) = \left\lbrace x \in \left\lbrace a,b \right\rbrace \,\middle\vert\, f(x) = 1 \right\rbrace\]For each $f_ i$:

- $\eta(f_ 1) = \left\lbrace a,b \right\rbrace$

- $\eta(f_ 2) = \left\lbrace a\right\rbrace$

- $\eta(f_ 3) = \left\lbrace b\right\rbrace$

- $\eta(f_ 4) = \emptyset$

This mapping respects the structure of $P(B)$, and the action of $\eta$ on morphisms (functions between sets) respects naturality.

To have a better feeling about “naturality” in Yoneda lemma, lets yet look at one last example. Let’s consider a simple category $\mathcal{A}$ with two objects and a few morphisms. Let $\mathcal{A}$ have objects $A$ and $B$, with the following morphisms:

- $\text{Hom}_ {\mathcal{A}}(A, A) = \left\lbrace \text{id}_ A \right\rbrace$

- $\text{Hom}_ {\mathcal{A}}(B, B) = \left\lbrace \text{id}_ B \right\rbrace$

- $\text{Hom}_ {\mathcal{A}}(B, A) = \left\lbrace f \right\rbrace$

We have $\mathcal{A}$ defined as follows:

\[\begin{array}{c|cc} \mathcal{A} & A & B \\ \hline A & \text{id}_ A & f \\ B & \varnothing & \text{id}_ B \\ \end{array}\]Define a contravariant functor $X: \mathcal{A}^{\text{op}} \to \text{Set}$. Let:

\[X(A) = \left\lbrace x \right\rbrace \quad \text{and} \quad X(B) = \left\lbrace y_ 1, y_ 2 \right\rbrace\]Now, let’s define how $X$ acts on morphisms. $X$ reverses the direction of morphisms, so we have:

\(X(\text{id}_ A) = \text{id}_ {X(A)} = \text{id}_ {\left\lbrace x\right\rbrace}\) \(X(\text{id}_ B) = \text{id}_ {X(B)} = \text{id}_ {\left\lbrace y_ 1, y_ 2\right\rbrace}\) \(X(f) : X(A) \to X(B) \quad \text{is a function mapping } x \text{ to either } y_ 1 \text{ or } y_ 2\)

Suppose $X(f)(x) = y_ 1$.

Now, consider the Yoneda embedding $H_ {A}$:

\(H_ {A}(A) = \text{Hom}_ {\mathcal{A}}(A, A) = \left\lbrace \text{id}_ A \right\rbrace\) \(H_ {A}(B) = \text{Hom}_ {\mathcal{A}}(B, A) = \left\lbrace f \right\rbrace\)

A natural transformation $\eta : H_ {A} \to X$ consists of functions $\eta_ B: H_ {A}(B) \to X(B)$ and $\eta_ A: H_ {A}(A) \to X(A)$ such that the following diagram commutes:

\[\begin{array}{c} X(A) \xrightarrow{X(f)} X(B) \\ \uparrow{\eta_A} \quad \quad \uparrow{\eta_B} \\ H_ {A}(A) \xrightarrow{H_ {A}(f)} H_ {A}(B) \end{array}\]More explicitly, it is

\[\begin{array}{c} \left\lbrace x \right\rbrace \xrightarrow{X(f)} \left\lbrace y_ {1},y_ {2} \right\rbrace \\ \uparrow{\eta_A} \quad \quad \quad \uparrow{\eta_B} \\ \mathbb{1}_ {A} \;\;\xrightarrow{H_ {A}(f)}\;\;f \;\;\;\;\; \end{array}\]where $\mathbb{1}_ {A}$ is another way to write $\text{id}_ {A}$, we will use them interchangeably. The naturality condition requires that

\[X(f)\,\circ\,\eta_ {A} = \eta_ {B} \,\circ\,H_ {A}(f).\]In our example, the components of $\eta$ are:

\(\eta_ A : H_ {A}(A) \to X(A), \text{ which is } \quad \eta_ A(\text{id}_ A) = x\) \(\eta_ B : H_ {A}(B) \to X(B), \text{ which is } \quad \eta_ B(f) = y_ 1\)

then the naturality condition requires that

\[\eta_ {B}: f\mapsto y_ {1},\]not $y_ {2}$, since we defined $X(f)$ to map $x$ to $y_ {1}$. This is the power of naturality condition!

Then, the Yoneda lemma says that $\text{Hom}(H_ {A}, X)$ is isomorphic to $X(A)=\left\lbrace x \right\rbrace$, that is, $\text{Hom}(H_ {A},X)$ consists of a single natural transformation $\eta$. There is no other way to construct a natural transformation, for example $\eta’$ such that $\eta’_ {B}:f\mapsto y_ {2}$, since it will violate the naturality condition.

3. The Proof of Yoneda Lemma

Let $\text{PSh}$ be the category of presheaves, that is the category of set-valued, contravariant functor with domain $\mathcal{A}$. It is also written as $[\mathcal{A}^{\text{op}},\text{Set}]$ or $\text{Hom}(\mathcal{A}^{\text{op}},\text{Set})$.

In order to prove the Yoneda lemma, we need to show that for any $a\in\mathcal{A}$ and $X\in \text{PSh}$, there exists a bijection (isomorphism) between $\text{Hom}(\mathcal{A}^{\text{op}},X)$ and $X(A)$.

Let’s define two maps:

- sharp map:

- flat map:

We will first construct ${\sharp}$ and $\flat$ maps, then demonstrate that they are mutually inverse, that is $\sharp\,\circ\,\flat=\flat\,\circ\,\sharp=\mathbb{1}$.

Given $\alpha: H_ {A}\to X$, $\alpha ^{\sharp}\in X(A)$. We need find an element in $X(A)$ so that we can identify $\alpha ^{\sharp}$ with it, that is how we construct the sharp map. Now, we don’t know anything about $X(A)$, except that $\alpha_ {A}$, namely the $A$-component of $\alpha$, maps $H_ {A}(A)$ to $X(A)$. Now we need to find an element in $H_ {A}(A)$ so we can apply $\alpha_ {A}$ on it, an obvious choice is simply $\mathbb{1}_ {A}$. $H_ {A}(\mathbb{1}_ {A})\in X(A)$, so we define

\[\boxed{ \alpha ^{\sharp} := \alpha_ {A}(\mathbb{1}_ {A}). }\]In a sense, we are using $\alpha$ to define $\alpha ^{\sharp}$.

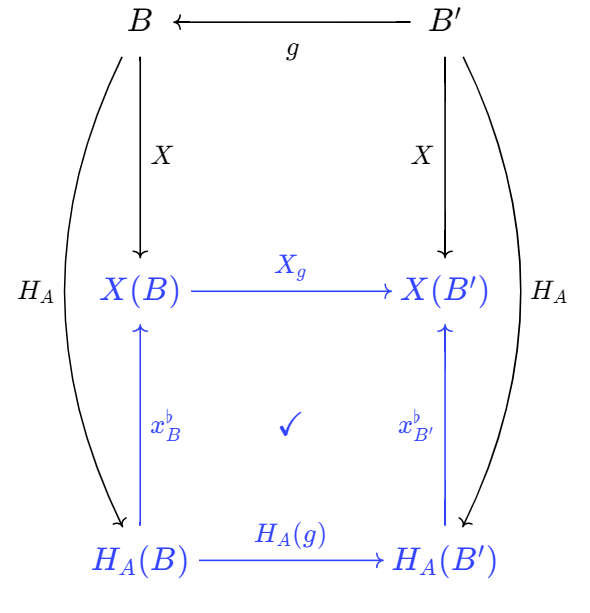

Next we move on to construct the flat map that maps $X(A)$ to $\text{Hom}(H_ {A},X)$. Let $x\in X(A)$, $x^{\flat} \in H_ {A}\to X$. If you draw all the relations down and stare at it for long enough, you will eventually find the way to construct $x^{\flat}$ from all the ingredients we have. To define $x^{\flat}$ we need to define each component of $x^{\flat}$. Let $B\in \mathcal{A}$ be any object, the $B$-component of $x^{\flat}$ (recall that $x^{\flat}$ is a natural transformation) maps $H_ {A}(B)$ to $X(B)$. Let $f\in H_ {A}(B)$, $f: B\to A$, thus $X(f):X(A)\to X(B)$. Write $X(f)$ as $X_ {f}$ for short. $X_ {f}(x)\in X(B)$, it is just what we needed, namely an element in $X(B)$, to define $x^{\flat}$! Now we can let

\[\begin{align*} x^{\flat}_ {B}: H_ {A}(B) &\to X(B), \\ f &\mapsto X_ {f}(x). \end{align*}\]Next we need to show that the naturality condition is satisfied. Naturality means that for any $B,B’\in\mathcal{A}$, in the following diagram the blue part commutes.

Follow the left-top path, $x^{\flat}_ {B}$ sends $f$ to $X_ {f}(x)$, then $X_ {g}$ sends it to $X_ {g}\,\circ\,X_ {f}(x)$. Follow the bottom-right path, $H_ {A}(g)=-\,\circ\,g$ sends $f$ to $f\,\circ\,g$, then $x^{\flat}_ {B’}$ sends it to $X_ {f\,\circ\,g}(x)$. Since $X$ is a contravariant functor, $X_ {f\,\circ\,g}=X_ {g}\,\circ\,X_ {f}$, thus these two different ways to compose arrows are the same!

Next, we show that $\sharp\,\circ\,\flat$ is identity map, which means that given any $x\in X(A)$,

\[(x^{\flat})^{\sharp}=x.\]Recall that, by construction for $\alpha \in \text{Hom}(H_ {A},X(A))$, $\alpha ^{\sharp}=\alpha_ {A}(\mathbb{1}_ {A})$. Apply this to $x^{\flat}$ we have

\[x^{\flat}=x^{\flat}_ {A}(\mathbb{1}_ {A}).\]Then

\[(x^{\flat})^{\sharp}=x^{\flat}_ {A}(\mathbb{1}_ {A}).\]How does the sharp map work? Given $y\in X_ {A}$ and any $B\in\mathcal{A}$, $y^{\flat}: f\mapsto X_ {f}(y)$, where $f\in \text{Hom}(B,A)$. Apply this to the above equation, let $f=\mathbb{1}_ {A}$ and $y=x$, we have

\[(x^{\flat})^{\sharp}=x^{\flat}_ {A}(\mathbb{1}_ {A}) = X_ {\mathbb{1}_ {A}}(x),\]Since $X$ as a functor must map $\mathbb{1}_ {A}$ to $\mathbb{1}_ {X(A)}$,

\[(x^{\flat})^{\sharp}=x^{\flat}_ {A}(\mathbb{1}_ {A}) = X_ {\mathbb{1}_ {A}}(x) = \mathbb{1}_ {X(A)}(x)=x.\]Next we need to show that $\flat\,\circ\,\sharp=\mathbb{1}$, that is

\[(\alpha ^{\sharp})^{\flat}=\mathbb{1}.\]First regard $\alpha ^{\sharp}$ as whole and perform the flat map. Let $B\in\mathcal{A}$ and $f\in H_ {A}(B)$, for the $B$-component of natural transformation $(\alpha ^{\sharp})^{\flat}$ we have

\[(\alpha ^{\sharp})^{\flat}_ {B}: f\mapsto X_ {f}(\alpha ^{\sharp}).\]Then performing the sharp map, $\alpha ^{\sharp}:\alpha\mapsto \alpha_ {A}(\mathbb{1}_ {A})$, thus

\[(\alpha ^{\sharp})^{\flat}_ {B}: f\mapsto X_ {f}(\alpha ^{\sharp}) = X_ {f}(\alpha_ {A}(\mathbb{1}_ {A})).\]To evaluate $X_ {f}(\alpha_ {A}(\mathbb{1}_ {A}))$ we need to use the naturality condition between $A,B\in\mathcal{A}$ and $f:B\to A$, which says the following two maps are identical:

\[\begin{align*} H_ {A}(A) &\xrightarrow{H_ {A}(f) =-\,\circ\,f}H_ {A}(B) \xrightarrow{\alpha_ {B}} X(B), \\ H_ {A}(A) & \xrightarrow{\alpha_ {A}}X(A)\xrightarrow{X_ {f}}X(B). \end{align*}\]Then \(X_ {f}(\alpha_ {A}(\mathbb{1}_ {A})) = \alpha_ {B}(f).\)

Thus we have

\[(\alpha ^{\sharp})^{\flat}_ {B}(f) = \alpha_ {B(f)} \implies (\alpha ^{\sharp})^{\flat} = \alpha.\]We have established the bijection between $\text{Hom}(H_ {A},X)$ and $X$, for each $A$ and $X$. For the last part of our proof, we need to show that this bijection is natural for all the $A$ and $X$.

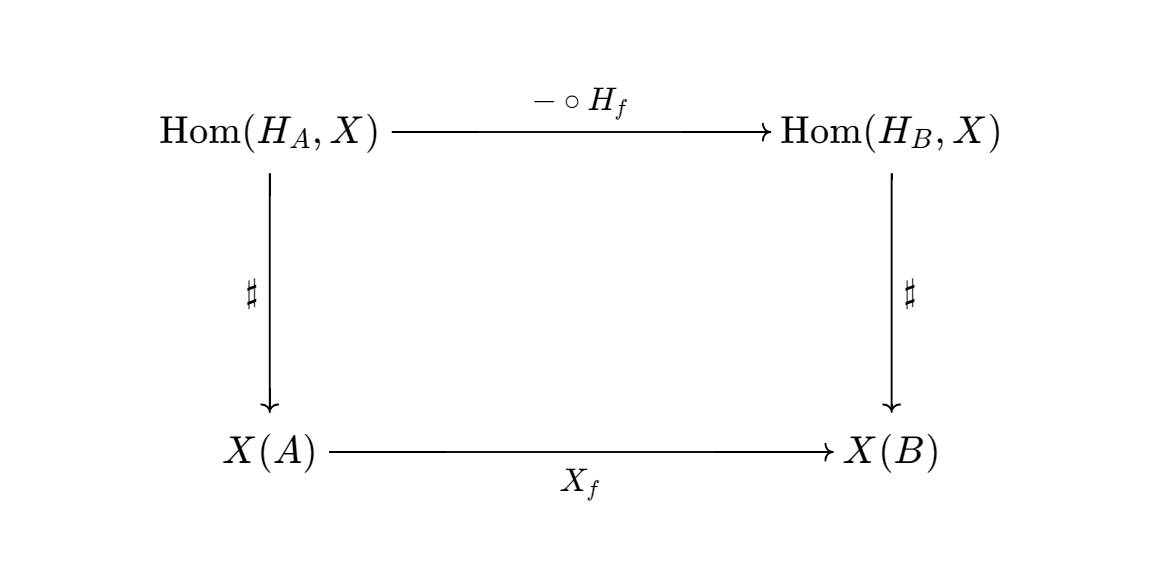

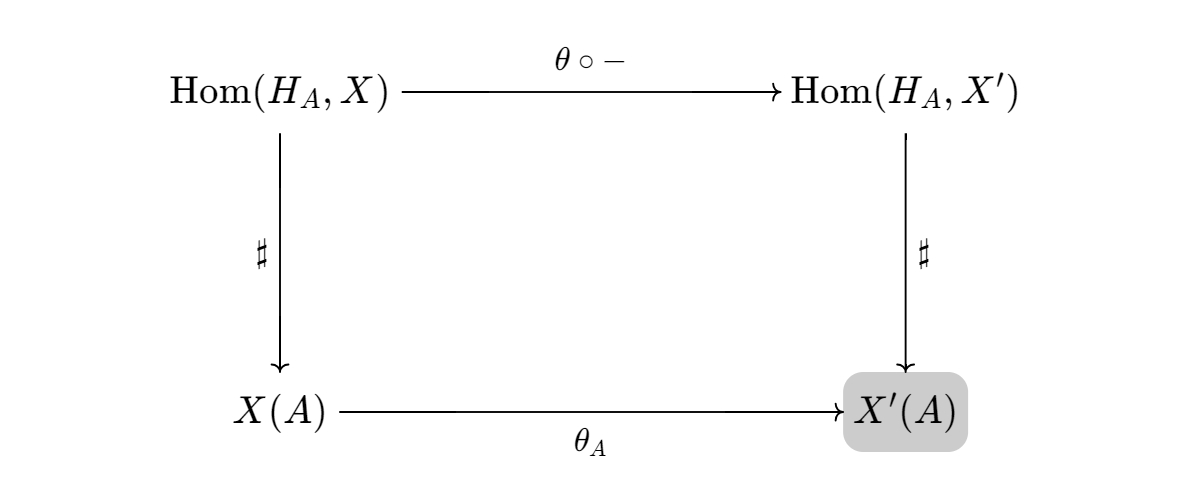

Naturality in $A$ states that for all $X$ and $B\in\mathcal{A}$, let $f\in H_ {A}(B)$, the following square commutes.

Natural transformation is a map between two functors, so when we talk about naturality in $A$, what functors are we talking about? One of them is the functor that maps $A$ to $\text{Hom}(H_ {A},X)$, let’s denote it by $\text{Hom}(H_ {\bullet},X)$; The other functor is just $X$.

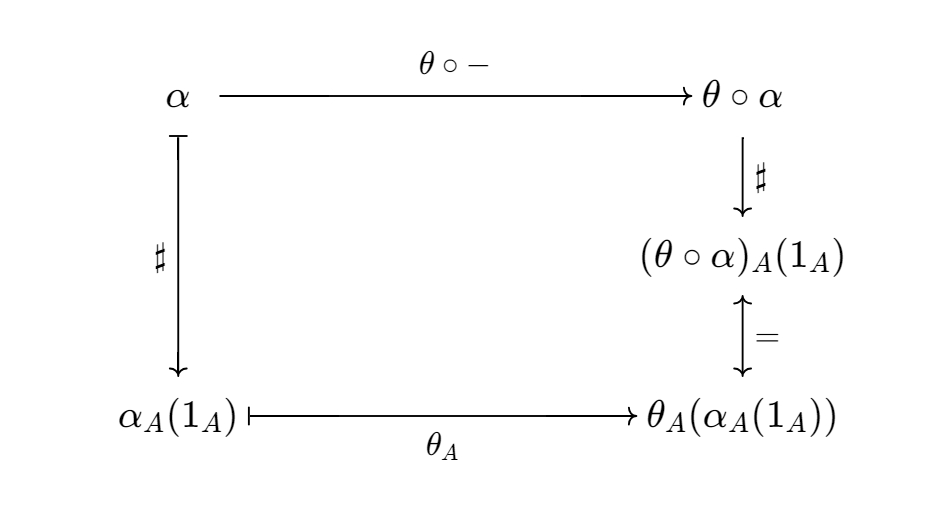

Let $\alpha \in \text{Hom}(H_ {A},X)$, recall that we constructed $A^{\sharp}$ by $A^{\sharp}=\alpha_ {A}(\mathbb{1}_ {A})$. The element-version of naturality in $A$ reads

Now we need to show that in the right-bottom corner, the equality holds. Since $H_ {f}:= f\,\circ\,-$,

\[H_ {f}(\mathbb{1}_ {B}) = f\,\circ\mathbb{1}_ {B}=f.\]Thus

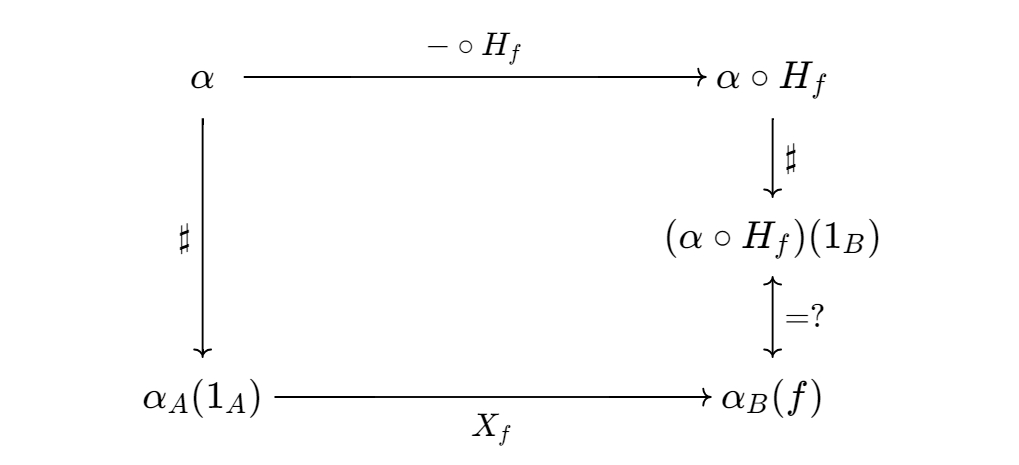

\[(\alpha \,\circ\,H_ {f})(\mathbb{1}_ {B}) = \alpha_ {B}(f).\]The naturality in $X$ is easier. It states that the following diagram commutes.

in terms of elements, we have the following diagram. It is obvious to see that it indeed commutes.

4. Consequences of the Yoneda Lemma

The Yoneda lemma is fundamental in category theory. Here we look at some important consequences.

Corollary 1. Let $\mathcal{A}$ be a locally small category. Let $X$ be a presheaf on $\mathcal{A}$. A representation of $X$ is an object $A\in\mathcal{A}$ together with one element $u\in X(A)$, such that for all $B\in \mathcal{A}$ and $x \in X(B)$, there is a unique map $\overline{x}:B\to A$ such that $X_ {\overline{x}}(u)=x$.

Recall that by definition, a representation is an $A\in \mathcal{A}$ and a natural isomorphism

\[\alpha: H_ {A} \xrightarrow{\sim}X\]where $\xrightarrow{\sim}$ means an isomorphism. The corollary then says that such pairs $(X,\alpha)$ are in natural bijection with pairs $(A,\mu)$, such that

\[X_ {\overline{x}}(u) = x.\]Pairs $(B,x)$ with $B\in\mathcal{A}$ are sometimes called elements of $X$. The element $u$ is sometimes called a universal element of $X$, since $u$ can point to anything in $X(B)$.

To prove the corollary, we need only to show that the natural transformation $u^{\flat}: H_ {A}\to X$ is an isomorphism, which means that $X$ indeed has a representation, namely $(A, u^{\flat})$, iff for all $B$ and $x\in X(B)$, there exists a unique $\overline{x}: B\to A$ such that

\[X_ {\overline{x}}(u) = x.\]By definition, $u^{\flat}$ is an isomorphism iff for all $B$,

\[u^{\flat}(B): H_ {A} (B) \xrightarrow{\sim} X(B).\]But we already have

\[u^{\flat}_ {B}(\overline{x}) = X_ {\overline{x}}(u)\]by construction, thus we have proved the corollary.

Another consequence of the Yoneda lemma is the following.

Corollary 2. For any locally small category $\mathcal{A}$, the Yoneda embedding

\[H_ {\bullet}: \mathcal{A} \to \text{Hom}(\mathcal{A}^{\text{op}},\text{Set})\]is full and faithful.

Informally, this says that for any $A,A’\in\mathcal{A}$, a map $H_ {A}\to H_ {A’}$ is the same thing as a map $A \to A’$.

We will now write down the detailed proof, but just mention that the key point is let $X$ in the Yoneda lemma

\[\text{Hom}(H_ {A},X) \cong X(A)\]to be $H_ {A’}$.

The word “embedding” is used to mean a map $A\to B$ that makes $A$ isomorphic to its image in $B$. For example, a bijection $F: A\to B$ may be called an embedding, for $A$ is isomorphic to its image $f(A)$ in $B$. Corollary 2 says that a full and faithful functor $F: \mathcal{A}\to \mathcal{B}$ can be reasonably called an embedding, as it makes $\mathcal{A}$ equivalent to its image in $\mathcal{B}$.

The third consequence of the Yoneda lemma is the following.

Corollary 3. Let $\mathcal{A}$ be a locally small category, and $A,A’\in\mathcal{A}$. Then

\[H_ {A}\cong H_ {A'} \Longleftrightarrow A\cong A' \Longleftrightarrow H^{A}\cong H^{A'}.\]We will also neglect the proof here.

Another interesting application of the Yoneda lemma can be found in Terrence Tao’s blog here, titled Yoneda’s lemma as an identification of form and function: the case study of polynomials. In his blog, Terrence Tao talked about formal polynomials, or polynomial forms $\mathbb{Z}[n]$ and polynomial functions $\mathbb{Z}[n]$. In the former, the indeterminate $n$ is a purely formal object, while in the latter, $n$ can take value in any ring $R$. Terrence Tao mentioned that

… one only interprets polynomial forms in a specific ring $R$, then some information about the polynomial could be lost (and some features of the polynomial, such as roots, may be “invisible” to that interpretation). But this turns out not to be the case if one considers interpretations in all rings simultaneously…

For example, consider the simplest linear formal polynomial $f=n$, it is different from $f=-n$. However, in the two-element ring $\mathbb{Z}_ {2}$, since for $a\in\mathbb{Z}_ {2}$, $a\equiv-a$.

Given a Polynomial form $P$ which can act on different rings, such as $R$ and $S$, we have

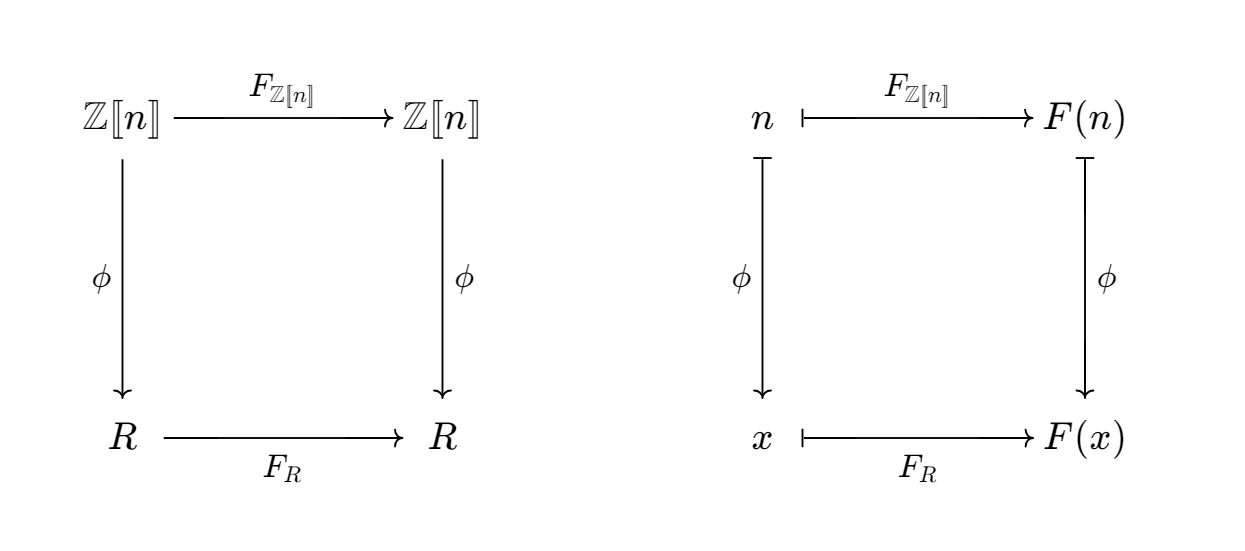

\[P: R\to R \quad \text{or} \quad S\to S.\]It is obvious, since given a formal polynomial $P(n)\in \mathbb{Z}[n]$, we can turn it into a polynomial function on ring $R$, which is a map $R\to R$, if we let $n=x$ for some $x\in R$, let’s denote it by $P_ {R}$. Similarly for ring $S$. Let $\phi: R\to S$ be a ring homomorphism, then we have the following commutation relation:

\[\phi \,\circ\, P_ {R} = P_ {S} \,\circ\, \phi\]It means that the ring homomorphism is compatible to polynomial functions, which is not so surprising. The surprising part is that the converse statement is also true: Let $F$ be a function that can act on different rings, for example if $F$ acts on a ring $R$, then we write

\[F_ {R} : R\to R,\]Similarly for ring $S$, $F_ {S}: S\to S$. Let $\phi: R\to S$ be a ring homomorphism. The statement is that, if

\[\phi \,\circ\,F_ {R} = F_ {S} \,\circ\, \phi\]holds for all rings and all homomorphisms, then $F=P$ for some polynomial form $P\in \mathbb{Z}[ [n] ]$. Note that $F$ could be any functions, but as long as it satisfies the condition, then it must be a polynomial function.

To better understand the statement, let’s set $A=\mathbb{Z}[[ n ]]$, turns out, $\mathbb{Z}[[ n ]]$ as an object in the category $\text{Ring}$ of rings is quite powerful, for the reason that we can construct a lot of arrows from it to other rings, it can see a lot, like the big brother from 1984.Apply the commutation relation between any function $F$ and $\phi$, where

\[\phi: \mathbb{Z}[[ n ]] \to R\]is the evaluation map, and let $x\in R$. For example, the action of $\phi_ {x}$ on $n$ is to give $n$ the value of $x$. The commutation relation is shown in the following figure, both in sets and in elements.

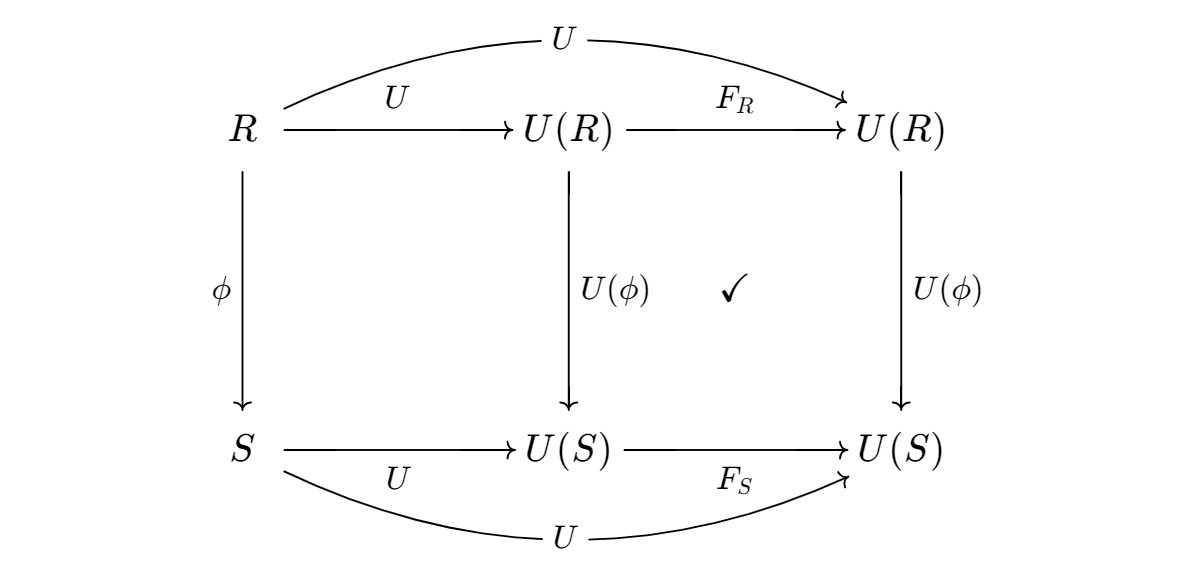

Now the Yoneda lemma comes into play. There are two categories at play here: $\text{Ring}$ and $\text{Set}$, and the forgetful

\[U: \text{Ring} \to \text{Set}\]is defined to map a ring $R$ to its underlying set $U(R)$, and maps a ring homomorphism $\phi$ to the corresponding function between sets $U(\phi)$.

Here is a change of perspective: the function $F$ can be regarded as a natural transformation! And we will show that the naturality condition is nothing but the commutation relation. As a natural transformation, it maps underling functor to underlying functor, for example, we said that

\[F_ {\mathbb{Z}[[ n ]] } : \mathbb{Z}[[n]] \to \mathbb{Z}[[n]]\]Now regard $F_ {\mathbb{Z}[[n]]}$ as the $\mathbb{Z}[[n]]$-component of $F$, and the right-hand-side actually should be a function not between $\mathbb{Z}[[n]]$, but between the underlying sets $U(\mathbb{Z}[[n]])$. Take $F_ {R}$ for example, $F_ {R}: R\to R$ should be in fact a function $F_ {R}: U(R) \to U(R)$.

The commutation relation between $\phi$ and $F$ is equivalent to the naturality condition, as is shown in the figure below.

The identification between the polynomial forms and functions can now be written as

\[U(\mathbb{Z}[[n]])\cong \text{Hom}(U,U)\equiv F.\]On the other hand, given an element $x\in R$, the evaluation map provides a map $\phi_ {x}: \mathbb{Z}[[n]] \to R$. Conversely, given an evaluation map $\phi$, we can identify an element $x\in R$ by evaluate $n$, that is $x_ {\phi}:=\phi(n)$. Thus the evaluation homomorphism provides a 1-2-1 correspondence between $R$ and maps in $\mathbb{Z}[[n]]\to R$. This correspondence is, again, at the level of sets $U(R)$ and $\text{Hom}(\mathbb{Z}[[n]],R)$. We write the correspondence in a form that applies for all the rings:

\[U(-) \cong \text{Hom}(\mathbb{Z}[[n]],-).\]Now come back to the last-last equation, in the second term in $\text{Hom}(U,U)$ we can rewrite the first $U$ as

\[U \cong \text{Hom}(\mathbb{Z}[[n]],-) = H^{\mathbb{Z}[[n]]},\]the identification between functions and polynomial forms can be written as

\[U(\mathbb{Z}[[n]]) ~===~ \text{Hom}(H^{\mathbb{Z}[[n]]},U),\]which is the familiar Yoneda lemma

\[X(A) \cong \text{Hom}(H^{A},X).\]Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: