Introduction to Resurgence Note 2

Series don’t just diverge for no reasons. The divergence of a series must reflect its cause….A divergent series is not meaningless, or a nuisance, but an essential and informative coded representation of the function. — Michael Berry

Resurgence aim to seeing things sub specie totius, from the perspective of the whole. It does not only re-sums divergent series, but also regenerates non-perturbative information from perturbative, and connects topological sector with trivial sector.

One more example: Euler’s equation

Let’s consider the Euler’s equation,

\[x^{2}f'-x+f=0\]and look for the solution of $f(x)$ on $\mathbb{R}$. This equation can be solved using the method of integrating factors, but we try to solve it using the method of power series. Assume the solution is of form

\[f = \sum_ {k=0} a_ {k} x^{k},\]substitute this to the equation and compare terms order-by-order, we get the following relation:

\[\begin{align*} a_ {0}&= 0, \\ a_ {1} &= 1, \\ (k-1) a_ {k-} &= -a_ {k} \text{ for } k\geq 2. \end{align*}\]Solving it we get

\[a_ {k} = (-1)^{k-1}(k-1)!,\]nice and simple. The only problem is that, the power series defined by it diverges for any $x$:

\[f(x) = \sum_ {k=0}^{\infty} (-1)^{k} k!x^{k+1},\]Also, we know that the solution of first order differential solution should have a constant of integral, which is a free parameter. But here we found no trace of it.

It turns out that, the method of power series can only find solutions that has a sensible Taylor expansion. Note that this method is aimed at finding the recursive relation between the coefficients of the power expansion of the possible solution, what if the solution has no sensible power expansion in the first place? It is not impossible, for some function are themselves well-defined, but indeed has trivial Taylor expansion about certain points. The most famous example of such functions, sometimes called non-perturbative, is $e^{ \bullet/x }$ at $x=0$, where $\bullet$ is any constant. We will see that the (family of) solutions that we are missing is indeed of such form.

The homogenous form of the Euler equation read

\[x^{2}g' +g=0,\]its solution has form

\[g(x) = a e^{ 1/x }, \quad a = \text{const}.\]Hence the general solution to the Euler equation is

\[f = \sum(\cdots) + g(x) = \sum(\cdots) + a e^{ 1/x },\]now $a$ is the missing constant of integral we are looking for.

Now the crisis of divergence still remains. This prolem can not be solved by shifting the point about which we expand the power series. In the previous case we are expanding about $x_ {0}=0$, have we changed it to $x_ {0}=c$ for some number $c$ would not render the power expansion to be convergent. To tackle the problem we must do something more radical. It is called the Borel resummation.

There are many approaches to resumming divergent series, such as Abel summation, Cesaro summation, $\zeta$-function regularization, etc. The method that is appropriate for our setting was introduced by Emile Borel in 1899, and is therefore called Borel summation.

Roughly speaking, we make use of an variation of Euler’s expression of functorial formula, to change the factorial (which is the reason for the divergence) into an integral:

\[k! x^{k+1} = \int_ {0}^{\infty} dt \, t^{k} e^{ -t/x } .\]Recall that the power series solution we got for Euler’s equation read

\[f(x) = \sum_ {k=0}^{\infty} (-1)^{k} k!x^{k+1},\]replace the $k!x^{k+1}$ term with the integral we get

\[f(x) = \sum \int (\cdots) = \int \sum (\cdots) = \int_ {0}^{\infty} dt \, \frac{1}{1+t} e^{ -t/x } .\]We have exchanged the order of integral and summation, which was actually not allow, but we do it anyway. That’s the secret of the method, later we will see that the reason why we got a divergent power series is that in obtaining the series, we have done a secrete exchange of integral and summation, which caused all the problems; the cure turns out to be the cause: we exchange it back!

The integral actually defines a nice smooth function when $x>0$. This function is called the Borel sum of our divergent series. Reader can verify directly that it is indeed a solution of the original function.

There exists a simple relation between the divergent series and the Borel-resummed function: The power series is the Taylor expansion of the function at $x=0$. Furthermore, we state without proof that the approximation given by the first $n$ terms of the series differs with the smooth function with an upper bound:

\[\left\lvert f(x) - \sum_ {k=0}^{n-1}(-1)^{k}k!x^{k+1} \right\rvert < n! \left\lvert x \right\rvert ^{n+1}.\]Integral Contour

The integral

\[\int_ {0}^{\infty} dt \, \frac{1}{1+t} e^{ -t/x }\]works fine when $x>0$, but what if $x<0$? The integral blows up!

At this point we need to expand our view and upgrade $x$ to a complex number. Now instead of living on the real number axis, $x$ lives on the 2D complex plane. Obviously the area on which the integral is well-defined is the half-plane where $\text{Re}(x)>0$. Then we can analytically continuate the value to the other half plane where $\text{Re}(x)<0$. This allows us to ask all kinds of interesting questions, for example what is the structure of the poles on the $\text{Re}(x)>0$ half-plane, after continuation what is the topological struction of the whole Riemann surface, what does the monodromy look like, etc. The question is, how to realize the analytical continuation?

To do so, it’s not enough to just complexify $x$, we need to do the same to the integral variable $t$, and modify the path of integral. Let $x=\left\lvert x \right\rvert e^{ i\theta }$. Define $\gamma_ {x}:= [0,\infty ] \cdot x = [0,\infty ] \cdot e^{ i\theta }$ to be the ray starting from the origin and passes through $x$, as long as the ray does not pass $-1$, which is a pole of the integrand, the integral is always well-defined:

\[\int_ {\gamma_ {x}} dt \, \frac{1}{1+t} e^{ -\left\lvert t \right\rvert e^{ i\theta }/\left\lvert x \right\rvert e^{ i\theta } } = \int_ {0}^{\infty} d \left\lvert t \right\rvert \, \frac{1}{1+\left\lvert t \right\rvert e^{ i\theta }} e^{ -\left\lvert t \right\rvert /\left\lvert x \right\rvert } <\infty.\]In this way we can define $f(x)$ for $x\in \mathbb{C} - \mathbb{R}^{-}$. The negative real line (include zero) is a branch cut of $f(x)$.

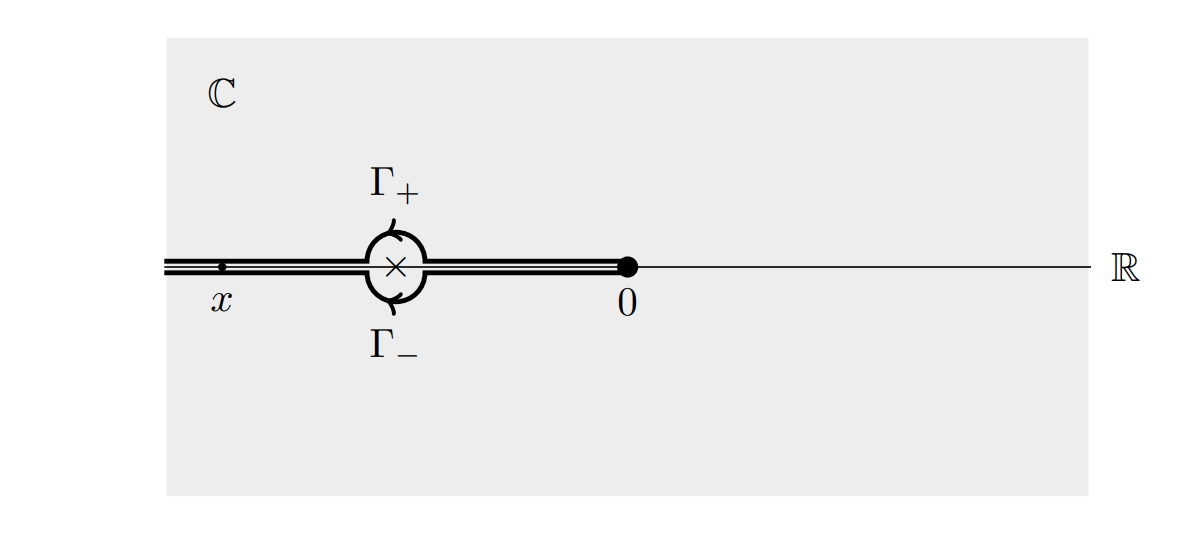

Since we can’t go pass the pole, can we avoid it with an infinitesimal half-circle? This is a trick commonly used in physics. The modified contour is shown in the figure below. The problem is, there are two ways to modify the contour, with path $\Gamma_ {+}$ and $\Gamma_ {-}$ respectively. Denote the corresponding integrals as $f_ {\pm}$:

\[f_ {+} (x) = \int_ {\Gamma_ {+}} \, (\cdots),\quad f_ {-} (x) = \int_ {\Gamma_ {-}} \, (\cdots).\]

Now, we can’t calculate $f_ {+}$ or $f_ {-}$ but we can calculate $f_ {+}-f_ {-}$. A simple integral by contour gives us

\[f_ {+}-f_ {-} = 2\pi i \text{Res}(t=-1) = 2\pi i e^{ 1/x }.\]Here pops up a non-perturbative term! Recall that the difference between two solutions is itself another solution, thus $e^{ 1/x }$ is another solution to the Euler equation. This is exactly the missing solution we were talking about. It is hidden in the complex structure of the Borel resummed functions.

This behavior, in which the function defined by a divergent series jumps along a ray, is an example of the Stokes phenomenon. It is the key to resurgence theory: the crucial missing term $e^{ 1/x }$ has “resurged”.

Borel (re)summation along $\mathbb{R}^{+}$

A rough idea

The Borel summation procedure is roughly as follows. Given a power series in $x$ (without a constant term),

\[f= \sum_ {k=0}^{\infty} a_ {k} x^{k+1},\]- Introduce a new variable $t$ to perform the

Borel transformation:

note that the power has changed from $x^{k+1}$ to $t^{k}$. The extra factor of $1 / k!$ is the key: it can make the originally divergent power series convergent.

- Perform the Borel resummation,

If the whole procedure works, for example if the integral does not encounter any singularity and does not involve further infinity, then we say that $f$ is Borel summable.

In general, there will be certain directions in which the singularities lie, such as $\mathbb{R}^{-}$ in the previous example. In most examples of physical interest, there will be infinitely many such singularities. These singularities carry important information about the functions that are defined by the divergent series. The theory of resurgence is about understanding the singularities, and how they affect the summation process.

Formal Borel transform

Here we follow the notation by Sauzin. Use $\mathbb{C}\left\lbrace z^{-1} \right\rbrace$ to denote polynomial with finite radius of convergence, they give as a holomorphic germ. Let $z^{-1}\mathbb{C}[[z^{-1}]]$ be formal power series without constant term, and let $\widetilde{\phi}$ be an element with it. The reason to exclude the constant term is so that it is more compatible with inverse Borel transform, as we will see shortly.

Borel transform takes $\widetilde{\phi}$ and tries to make it more convergent, by dividing the $n$-th coefficient by $n!$. To be exact, the Borel transform is the linear map

\[\mathcal{B}:\quad \widetilde{\phi}:=\sum_ {n\geq 0}a_ {n} z^{-n-1} \mapsto \hat{\phi} := \sum_ {n\geq 0} \frac{a_ {n}}{n!} \zeta^{n}.\]The notation tilde and hat are used by Sauzin, and the change of indeterminate from $z$ to $\zeta$ is customary. Note that the power is shifted, $a_ {0} z^{-1}$ is mapped to $a_ {0} \zeta_ {0}=a_ {0}$, a constant term in $\hat{\phi}$.

If $\widetilde{\phi}$ is already convergent with a finite radius of convergence, then $\hat{\phi}$ converges even better, its radius of convergence is $\infty$. To see this, note that if $\widetilde{\phi}$ is convergent, its terms must be bounded by

\[a_ {n} \leq A c^{n}, \quad A,c>0.\]The resulting $\hat{\phi}$ is a exponentially bounded function, it is $\leq Ae^{ c\left\lvert \zeta \right\rvert }$ on the entire complex plane.

To prove the inverse, that if $\hat{\phi}$ is an entire function of bounded exponential type then $\widetilde{\phi}$ defines a germ, we need to use Cauchy’s inequality that gives an upper bound of the derivative of a holomorphic function. We will not go to details here.

Gevrey classes

The Gevrey classes of formal power series describe different levels of growth for the coefficients of a formal power series. A formal power series

is said to be of Gevrey order $s$, or Gevrey type $s$, where $s > 0$, if there exists constant $A,B > 0$ such that:

\[\left\lvert a_ {n} \right\rvert \leq A B^{n} (n!)^{s} \quad \;\forall\; n\geq 0.\]If $s = 1$, the series is called 1-Gevrey (or simply Gevrey). If $s < 1$, the series is closer to an analytic function (with a better convergence rate). Many divergent but resummable functions are of Gevrey type 1.

1-Gevrey formal power series constitutes a vector space, which we will denote by $\mathbb{C}[[z^{-1}]]_ {1}$. These formal power series can be Borel-resummed to give a holomorphic germ. In more mathematical terms, we have the following:

Let $\widetilde{\phi}\in z^{-1} \mathbb{C}[[z^{-1}]]_ {1}$, note that there is no constant term. Then the Borel transformed series $\hat{\phi}$ gives a holomorphic germ (having a positive radius of convergence), namely $\hat{\phi}\in \mathbb{C}\left\lbrace z^{-1} \right\rbrace$. Vise versa.

Sometimes we will denote $z^{-1} \mathbb{C}[[z^{-1}]]_ {1}$ as $\mathcal{B}^{-1}(\mathbb{C}\left\lbrace z^{-1} \right\rbrace)$.

Let $T_ {c}$ be the translation operator, defined by

\[T_ {c} f(z) := f(z+c),\]it can be shown that

\[\mathcal{B} T_ {c}\widetilde{\phi} = e^{ -c\zeta } \mathcal{B}\widetilde{\phi}.\]So far we haven’t talked about why it has to be without constant terms. Another question is, why doesn’t 1-Gevrey formal power series $\mathbb{C}[[z^{-1}]]_ {1}$ form an algebra? That is to ask, why doesn’t the multiplication of two 1-Gevrey series 1-Gevrey? To study that we need the concept of convolution.

Convolution

Let $\widetilde{\phi}, \widetilde{\psi}$ be Borel transformed to $\hat{\phi}$, $\hat{\psi}$ respectively. The convolution is defined between Borel-transformed objects, between $\hat{\phi}$ and $\hat{\psi}$. The convolution $\ast$ is defined as

\[\hat{\phi}\ast \hat{\psi} := \mathcal{B}\left\lbrace \widetilde{\phi}\widetilde{\psi} \right\rbrace .\]In other words, convolution is defined as the image of Borel transform of multiplication.

If $\hat{\phi}$ and $\hat{\psi}$ define two holomorphic germs, denoted as $\Phi$ and $\Psi$ respectively, then the convolution appears as the familiar form:

\[\Phi \ast \Psi(\zeta) = \int_ {0}^{\zeta} \, \Phi(t)\Psi(\zeta-t) dt.\]A difference between convolution $\ast$ and multiplication is that, so far we haven’t defined a unit element with respect to convolution. The functional form of convolution inspires as to introduce the delta function $\delta$ as an abstract unit element,

\[\delta \ast \Psi (\zeta) = \Psi(\zeta).\]Then $\delta \oplus \mathbb{C}[[\zeta]]$ form an algebra under convolution. We also define the preimage of $\delta$ under Borel transform to be $1$ in $z^{-1}\mathbb{C}[[z]]$.

The fine Borel-Laplace summation

Let $S_ {\delta}$ be a half strip of width $2\delta$:

\[S_ {\delta} := \left\lbrace \zeta \in \mathbb{C} \,\middle\vert\, \text{dist}(\zeta,\mathbb{R}^{+}) <\delta\right\rbrace ,\]where $\text{dist(a,S)}$ is the distance between element $a$ and set $S$.

Let $\mathcal{N}_ {c_ {0}}(\mathbb{R}^{+})$ be the sheaf of analytic functions $\hat{\phi}(\zeta)$ on $S_ {\delta}$ which is bounded by

\[\left\lvert \hat{\phi}(\zeta) \right\rvert \leq Ae^{ c_ {0}\left\lvert \zeta \right\rvert }.\]We also define

\[\mathcal{N}(\mathbb{R}^{+}) := \bigcup_ {c_ {0}\in \mathbb{R}}\mathcal{N}_ {c_ {0}}(\mathbb{R}^{+}).\]Appendix

Here are some related definitions and concepts.

A resurgent function is a an analytic function of $1$ complex variable obtained by Borel-Laplace summation method, from a resurgent series. This is not really a strict definition but rather an explanation.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: