Mass Renormalization

Model and convention

As an example to illustrate the idea of mass renormalization, we consider the so-called Model 3 by Sydney Coleman, with one real scalar $\phi$ and one complex scalar $\psi$:

\[\mathcal{L} = \frac{1}{2}(\partial \phi)^{2}- \frac{1}{2}\mu^{2}\phi^{2} + \left\lvert \partial \psi \right\rvert ^{2}- m^{2}\psi ^\ast \psi - V,\]where $V$ is a Yukawa-like potential

\[V = g \psi^{\ast} \psi \phi.\]$\phi$ is called meason and $\psi$ is called nucleon.

The four-momentum eigenstate is defined by

\[\left\lvert p \right\rangle := (2\pi)^{3/2} \sqrt{2\omega_ {p}} \left\lvert \vec{p} \right\rangle\]where $\left\lvert \vec{p} \right\rangle$ is the 3-momentum state, $\left\lvert \vec{p} \right\rangle=a_ {\vec{p}}^{\dagger}\left\lvert 0 \right\rangle$.

Effective mass

Immanuel Kant argues that we can never directly access ding an sich, thing-in-itself, the objective reality independent of our perception. Instead, we can only know objects as they appear to us through our senses, structured by the cognitive framework imposed by our mind. By the way, Kant has his own “category theory”, it has nothing to do with the category theory by Mac Lane and others.

Physics does not directly access fundamental parameters (such as mass, charge). It is not only true experimentally, but also true theoretically. Take mass $m$ for example, we don’t know what is its raw form; instead, we define it through equations, such as Newton’s second law $F=ma$, and we infer its value by measurements. These measurements can never prove Newton’s second law for there is always room for new theory hiding in the error or accuracy in experiments; instead the measurements can only say that the experiments didn’t falsify the theory up to what accuracy. I am a Popperist in this sense.

Borrowing the words from Kantian epistemology, theories consist the categories of understanding that shape all human knowledge. What we study are the phenomena, the measurable, empirical consequences of the underlying reality. Physics theories provide a framework for describing these empirical observations. In a Kantian sense, these are part of the phenomenal world—models that help us systematize experience, rather than direct insights into the noumenon, which is the inherent essence, thing-in-themselves.

For example, we can define the mass using inertia: $F = ma$. However, you can define the mass using another equally plausible equation: $F = mg$, which is the gravitational force. Different phenomena gives different noumena, we have two very different concepts of masses. The fact that they are equivalent to each other has profound meaning, this equivalence is not a analytical knowledge, but synthetic knowledge. It says that gravitation is actually the same thing as acceleration.

To have a feeling of what effective mass is, consider a rigid sphere of volume $V$, immersed in a perfect fluid (with zero viscosity) of density $\rho$. Let $m_ {0}$ be the “bare” mass of the ball, $\rho$ be the density of the water, and suppose

\[m_ {0}= \frac{1}{10} \rho V.\]The buoyancy force is $\rho V$ and the gravitational force is $m_ {0}g$. The total force exerted on the ball is $9m_ {0} g$, so if we let go of the ball, it should accelerate upward with acceleration $9 g$. However, in reality this never happens, because the ball has to spread the water and that costs energy. There is also the frictional force, but that is only important when the ball has already gained some velocity. A more realistic case is that, when you let go the ball, the acceleration is around $a=\frac{3}{2}g$, instead $a=9 g$. Now if you insist on using $F=ma$ to define the mass of the moving ball, then we have

\[F = 9 m_ {0} g = m a = m \frac{3}{2} g\implies m = 6 m_ {0}.\]We can say the when immersed in the liquid, the ball has effective mass $6m_ {0}$. But it is really the way that you decided to interpret the experiment.

I will not talk about the bump function $f(t)$ since it is really problematic. Actually, you can write down a smooth $C^{\infty}$ bump function explicitly. Define

\[h(t) = \begin{cases} e^{ -1 / t }, & t>0 , \\ 0, & t\leq 0, \end{cases}\]$h(t)$ is smooth. Given any real numbers $t_ {1}$ and $t_ {2}$ such that $t_ {1}<t_ {2}$, define

\[f(t) = \frac{h(t-t_ {1})}{h(t-t_ {1})+h(t_ {2}-t)}\]then

\[f(t) = \begin{cases} 0, & t<t_ {1}, \\ [0,1], & t_ {1}<t<t_ {2}, \\ 1, & t>t_ {2}. \end{cases}\]However, the free theory is not smoothly connected to the interacting theory. It is like expanding an algebraic equation

\[\epsilon x^{4}+ax^{2}+c=0,\]when $\epsilon=0$ there are two roots, when $\epsilon \neq 0$ there are four roots, the extra two solutions goes to infinity as $\epsilon\to 0$, if we want to talk about these two extra roots, it doesn’t help to expand about $\epsilon=0$. So I’ll try to leave the bump function out of this talk.

In general, whenever a particle is interacting with a continuum system, may it be perfect fluid or electric-magnetic field, or any other field, the mass of the particle changes from when there is no interaction.

Consider the meson only for now, the relevant terms are

\[\mathcal{L} = \frac{1}{2}(\partial \phi)^{2} - \frac{1}{2}\mu_ {0}^{2}\phi^{2}-g\psi ^\ast \psi \phi+\cdots\]where in the spirit of previous discussion, we write $\mu_ {0}$ instead of $\mu$. $\mu_ {0}$ is the bare mass of the meson, whose value can not be measured directly. Compare to our previous example of a ball, this Lagrangian corresponds to $F=m_ {0} a$ when the ball is free, not in water.

In real world there is interaction. The physical mass $\mu$ of the meson is dressed up by the interaction,

Even there is interaction, the $S$ matrix element for vacuum to vacuum should be $1$. To ensure that, we need to introduce the constant counter term $a$, which should be added to the Lagrangian density, $\mathcal{L}=\cdots+a,$

\[a \text{ is fiexed by } \left\langle 0 \right\rvert S \left\lvert 0 \right\rangle=1.\]We can write $\mu_ {0}^{2}=\nu^{2}-b$ and $m_ {0}^{2}=m^{2}-c$. This introduces the mass renormalization terms $\frac{1}{2} b\phi^{2}$ and $c \psi ^\ast\psi$,

\[b,c \text{ are fixed by } \left\langle \vec{p} \right\rvert S \left\lvert \vec{p}' \right\rangle = \delta^{3}(\vec{p}-\vec{p}').\]where $\vec{p},\vec{p}’$ are momentum of mesons and nucleons.

Feynman Rules

Wick diagrams are used to calculate the time-ordered operators, Feynman diagrams are used to calculate the $S$-matrix. Wick diagrams don’t pay attention to loose external lines, but Feynman diagram does.

Consider the $\psi \psi\to\psi \psi$ scatter,

\[N(\vec{p}_ {1})+N(\vec{p}_ {2})\to N(\vec{p}_ {1}')+N(\vec{p}_ {2}'),\]The $\mathcal{O}(g^{2})$ $S$-matrix element we want to calculate is $\left\langle \vec{p}_ {1}’\vec{p}_ {2}’ \right\rvert(S-1)\left\lvert \vec{p}_ {1}\vec{p}_ {2} \right\rangle$. The term in $S-1$ of $\mathcal{O}(g^{2})$ is

\[\frac{1}{2}\int d^{4}x_ {1}d^{4}x_ {2} \, \mathcal{T}(-i\mathcal{H}_ {I}(x_ {1}))(-i\mathcal{H}_ {I}(x_ {2}))\]which is

\[\frac{1}{2}(-ig)^{2}\int d^{4}x_ {1}d^{4}x_ {2} \, \mathcal{T} \psi ^\ast_ {1}\psi_ {1}\phi_ {1}\psi_ {2}^\ast \psi_ {2}\phi_ {2}\]where $\psi_ {1}$ is short for $\psi(x_ {1})$, etc.

This is just the time-evolution, it acts on the initial and final states, which we will take care of now. All the fields that are going to annihilate a particle in the initial state will be put to the right, where the initial state is. All the fields that are gonna contract particles in the final state will be put to the left, where the final state is. We will label the external legs with the momenta of corresponding particles.

Let’s calculate the external lines first. With our convention, the contraction with an incoming particle with momentum $p$ gives a factor $e^{ -ip\cdot x }$. We have

\[\left\langle \vec{p}_ {1}' \vec{p}_ {2}' \right\rvert \mathcal{N}\left\lbrace \psi_ {1}^\ast \psi_ {1}\psi_ {2}^\ast \psi_ {2} \right\rbrace \left\lvert \vec{p}_ {1}\vec{p}_ {2} \right\rangle = \left\langle \vec{p}_ {1}' \vec{p}_ {2}' \right\rvert \psi_ {1}^\ast \psi_ {2}^\ast \psi_ {1} \psi_ {2} \left\lvert \vec{p}_ {1}\vec{p}_ {2} \right\rangle\]which is a bunch of phases:

\[e^{ ix_ {1}\cdot(p_ {1}'-p_ {1})+ix_ {2}\cdot(p_ {2}'-p_ {2}) }+e^{ ix_ {1}\cdot(p_ {1}'-p_ {2})+ix_ {2}\cdot(p_ {2}'-p_ {1}) } + (x_ {1}\longleftrightarrow x_ {2}).\]Note that the exchange of two vertices $x_ {1}\longleftrightarrow x_ {2}$ will cancel the factor $\frac{1}{2}$ in Dyson’s formula.

The contraction between two meson field was calculated before,

\[\text{contraction} \left\lbrace \phi_ {1}\phi_ {2} \right\rbrace =\int \frac{d^{4}p}{(2\pi)^{4}} \, e^{ -iq(x_ {1}-x_ {2}) } \frac{i}{q^{2}-\mu^{2}+i\epsilon}.\]Now we can insert all of them into the $\mathcal{O}(g^{2})$ term, the $x_ {1},x_ {2}$ integrals can be done explicitly since they just give a delta function,

\[\begin{align*} \left\langle \vec{p}_ {1}' \vec{p}_ {2}' \right\rvert S-1 \left\lvert \vec{p}_ {1}\vec{p}_ {2} \right\rangle =& (-ig)^{2}\int \frac{d^{4}q}{(2\pi)^{4}} \, \frac{i}{q^{2}-\mu^{2}+i\epsilon} \\ &\times \int d^{4}x_ {1} d^{4}x_ {2} \, e^{ ix_ {1}\cdot(p_ {1}'-p_ {1}-q)+ix_ {2}\cdot(p_ {2}'-p_ {2}+q) }+(p_ {1}\longleftrightarrow p_ {2}). \end{align*}\]Since

\[\int d^{4}x \, e^{ ipx } = (2\pi)^{4}\delta (p)\]and $\delta(x-a)\delta(x-b)=\delta(a-b)\delta(x-a)$, we have

\[\begin{align*} \left\langle \vec{p}_ {1}' \vec{p}_ {2}' \right\rvert S-1 \left\lvert \vec{p}_ {1}\vec{p}_ {2} \right\rangle =& (-ig)^{2}(2\pi)^{4} \delta^{4}(p_ {1}'+p_ {2}'-p_ {1}-p_ {2})\\ & \times \int \frac{d^{4q}}{(2\pi)^{4}} \,(2\pi)^{4} \frac{i}{q^{2}-\mu^{2}+\epsilon}[\delta^{4}(p_ {1}'-p_ {1}-q)+\delta^{4}(p_ {2}'-p_ {1}+q)]. \end{align*}\]The RHS of the first line gives us the conservation of total momentum. We can define the invariant Feynman amplitude $\mathcal{A}$ as

\[\left\langle f \right\rvert S-1\left\lvert i \right\rangle =i (2\pi)^{4}\delta^{4}\left( \sum p \right) \mathcal{A}\]Then in our example

\[\mathcal{A} = (-ig)^{2} \frac{1}{(p_ {1}'-p_ {1})^{2}-\mu^{2}+i\epsilon} + (-ig)^{2} \frac{1}{(p_ {2}'-p_ {1})^{2}-\mu^{2}+i\epsilon} ,\]they corresponds to the following two diagrams:

Draw $t,u$-channel diagrams and calculate one of them.

See page 256 of Coleman’s lecture.

Talk about a 1-loop example $\mathcal{O}(g^{4})$ diagram.

The contractions are called propagators, which is not really some particle propagating in spacetime. Factors like $i / (q^{2}-\mu^{2}+i\epsilon)$ give the probability amplitude, in this metaphorical language, for the virtual particle going between two vertices. They describe how a virtual particle propagates from one vertex to another. For this reason, they are called Feynman propagators. The language, I stress, is purely metaphorical. If you don’t want to use it, don’t use it. But then you’ll find 90% of the physicists in the world will be unintelligible to you when they give seminars. It’s very convenient, but it should not be taken too seriously.

March 24th

Feynman diagrams in Model 3 to order $g^{2}$

The a counterterm is just a number. I don’t need a special diagrammatic rule for that. The a counterterm has no momentum associated with it, and its delta function has an argument of zero. If the system were in a box, the term $(2\pi)^{4}\delta^{4}(0)$ would turn into $VT$, the volume of spacetime in the box. This counterterm is designed to cancel all the vacuum bubble diagrams, those without external lines, which you will see also have a factor of $(2\pi)^{4}\delta^{4}(0)$. Like the counterterm a, the counterterms $b$ and $c$ will be expressed as infinite power series in the coupling constant $g$. I will explain to you shortly how we determine them order by order.

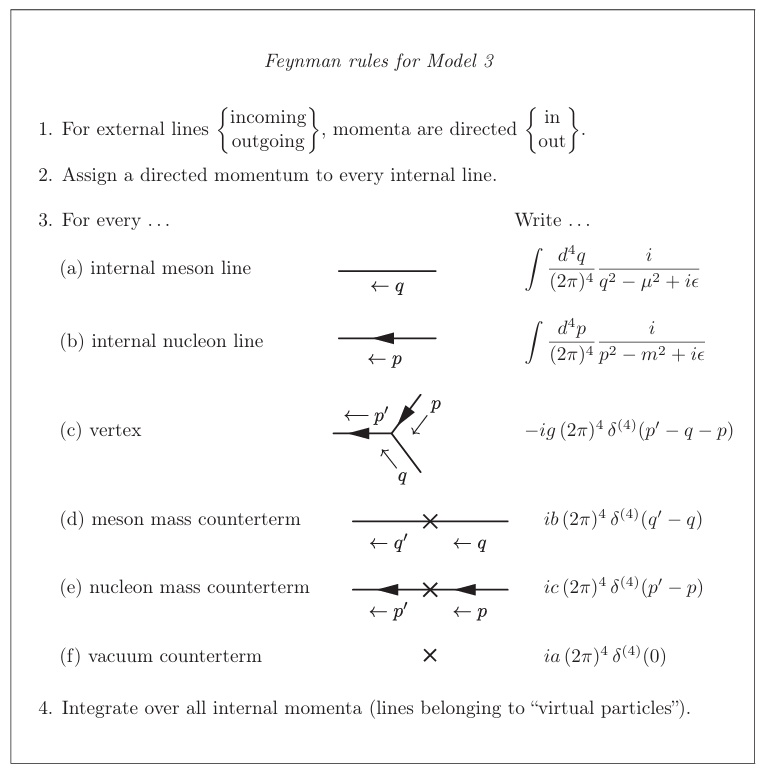

The Feynman rules for model three are shown in the figure below.

For Feynman diagrams, see Page 261 in Sydney Coleman’s book.

Regarding the $\mathcal{O}(g^{2})$ correction to meson mass. Here is where we need counterterm $b$. The renormalization condition that fixes be is define as following: there is no phase mismatch between one-meson states $\left\lvert \vec{q} \right\rangle$ and $\left\lvert \vec{q}’ \right\rangle$,

\[\left\langle \vec{q} \right\rvert S \left\lvert \vec{q}' \right\rangle = \delta^{3}(\vec{q}-\vec{q}').\]which in terms of invariant amplitude reads

\[\left\langle \vec{q} \right\rvert S-1 \left\lvert \vec{q}' \right\rangle =0.\]It means that the sum of two diagrams is zero.

It is nearly the same story for the nucleon. See page 262.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: