A Passive Perspective of Linearized Soliton Perturbation Theory

Quantization and Haag Theorem

This section can be entirely skipped for readers who are not interested in Haag’s theorem.

Quantization

Start with a classical theory with Lagrangian $\mathcal{L}$, or equivalently Hamiltonian $H$. There may be some symmetry group $G$ acting on the Lagrangian. The theory can be separated into free part and interacting part. Upon quantization, the interaction will introduce an UV energy scale $\Lambda_ {\text{UV}}$ above which the theory becomes invalid. The symmetry group $G$ might break, if it is solely due to the quantization procedure then we say the symmetry is anomalous. The classical Hamiltonian are functions of canonical variables $q$ and $p$. The canonical variables satisfy certain Poisson brackets, which generates the dynamics of the model.

Let’s ignore the interaction for now and deal with a free theory only. We will introduce interaction later and see that they cause fundamental difficulties in quantization. But without interaction, things are under control. To quantize a classical model we need to construct a Hilbert space in a self-consistent way. The simplest procedure is to upgrade the generalized coordinates and canonical momenta to operators, then map the Poisson bracket to the so-called canonical commutation relation (CCR),

\[[q,p] = i\hbar.\]The Hilbert space we are looking for is a representation of CCR. there exist different possible representations, for example $q,p$ could be represented by matrices; or we could let $q=q$ and $p=-i\hbar \frac{ \partial }{ \partial q }$, the corresponding Hilbert space is the Lebesgue space $L^{2}(\mathbb{R}^{d})$, which is the square-integrable functions quotient functions with measure zero almost everywhere, such as the famous Dirichlet function.

Classical functions $f(q,p)$ are quantized in a straightforward way, by replacing $q$ and $p$ by their corresponding operators.

This procedure has a number of problems. For example, it is not consistent in the sense that the quantization of $f(q,p)$ is usually not unique due to different orders of $p,q$. Later people proposed better, more sophisticated quantization methods, such as geometry quantization and deformation quantization. So it is safe to say that, given a free classical theory, we can quantize it to obtain a Hilbert space for free quantum theory.

Given a CCR there exist multiple irreducible representations, so the question is, are they unitarily equivalent to each other, that is, do they give the same physical results? In quantum mechanics we deal with finite dimensional CCR and this question is answered by the Stone-von Neumann theorem, which claims that all the representations are equivalent up to a unitary transform. This makes sure that whatever representation we choose, we will get the same prediction for observables. However, it turned out later that if $U(1)$ gauge field is included, this claim is no longer true. I am still not sure about this claim, but it seems to suggest that even in the finite dimensional case, a single irreducible representation, up to unitary transform, is already not enough when there is electro-magnetic field around.

One way to think of the quantization of quantum field theory is to start from quantum mechanics, generalize $p$ and $q$ to $\phi(\vec{x})$ and $\pi(\vec{x})$, going from finite dimensional CCR of quantum mechanics to infinite dimensional CCR of quantum field theory. This way we start from a well-established CCR algebra and generalize its dimension to infinity. Another way is to start from a classical field theory, say, a scalar classical Landau-Ginsberg model, with real scalar field $\phi(\vec{x})$. Let $M$ be the space manifold, the configuration space of a classical field theory is denoted as $\mathcal{C}(M,\mathbb{R})$ where $\mathbb{R}$ is the time direction. Regard $\vec{x}$ as continuous indices as in quantum field theory, then $\vec{x}$ labels different field operator, and each $\phi(\vec{x})$ can be considered as a functional, it is the evaluation functional on the configuration space, explicitly let $f\in\mathcal{C}$ then

\[\phi(\vec{x}): \mathcal{C} \to \mathbb{R},\quad f \mapsto f(\vec{x}).\]A general field is a function $F$ of the basic field $\phi$, $F=F(\phi)$. Then $F(\phi)$ is also a functional on $\mathcal{C}$. The advantage of this point of view is that, first, in particular in view of deformation quantization, it is a main advantage of our approach that the fields of both the classical and the quantum theory are defined in terms of the same space of functionals. Second, many of the most fundamental and profound phenomenon in quantum field theory, such as renormalization group flow or critical behavior, already takes place in classical field theory level. This approach greatly increases our understanding of quantum field theory.

For quantum field theory, we can borrow the Hilbert space constructed in quantum mechanics and expand it to Fock space, sometimes know as second quantization. Compare to coming up to a Hilbert space from nothing, the construction of Fock space is quite straight forward, that’s why Edward Nelson said something like the first quantization is a mystery and the second quantization is a functor.

However, recall that this Fock space is built up from free states, there is no interaction involved yet. The eigen states are supposed to be that of free particles with mass $m$, whose energy is $\sqrt{\vec{p}^{2}+m^{2}}$. To deal with interaction, the standard procedure is to turn to interaction picture, or Dirac picture. In interaction picture, the operators are evolved by free Hamiltonian without interaction, and the states alone are evolved by interact. This allows us to easily write down the time dependence of field operators, then it is easy to write down the Feynman propagators, etc.

There are some fundamental issues regarding the good old interaction picture that I haven’t figured out, and I mean the so-called Haag’s theorem, or more accurately Haag-Hall-Wightman (HHW) theorem, which roughly says that interaction picture is inconsistent, even in the case of neutral free scalar field with different masses. It claims that the set of assumptions required to construct the interaction picture is only consistent when there is no interaction. It also claims that non-Fock representations have an important rule to play in QFT (Earman and Fraser, 2006). Our work on kinks will provide an explicit example.

As we mentioned before, quantum theories, no matter quantum field theory or quantum field theory are described by a bunch of canonical commutation relations (here we only consider bosonic case), such as $[x,p]=i\hbar$ or $[\phi(\vec{x}),\pi(\vec{y})]=(2\pi)^{d}\delta^{d}(\vec{x}-\vec{y})$. In quantum mechanics we have finite sets of independent CCR’s (canonical commutation relation), while in quantum field theory we have infinite dimension. Things usually get quite messy when going from finite to infinity, properties that hold in the finite case may not hold for infinite case, for example a sum of finite positive numbers are always positive, but a sum of infinite positive numbers may not be positive anymore. The same thing happens with going from quantum mechanics to quantum field theory.

Haag-Hall-Wightman theorem

Fock space is only one representation among an uncountable infinity of Hilbert space representations (Garding & Wightman, 1954). So why Fock representation? Haag was motivated by this choice question to formulate his theorem. Later turns out that there exists so-called strange representation, which by definition is any representation of free field that is unitarily inequivalent form Fock space. The determination of representation is a dynamical problem. Like Florig and Summers (2000) said,

The kinematical aspects determine the choice of CCR-algebra, whereas the dynamics fix the choice of the representation.

The vacuum state can be specified in two ways: (1) it is the minimal energy state; (2) it is the unique state annihilated by particle number operator $a^{\dagger}a$. If these two specification don’t coincide, the vacuum is said to be polarized. As we will see later, the presence of a kink will polarize the trivial vacuum. Vacuum polarization lies at the core of HHW theorem, any interacting quantum field operator, or free fields of different masses, polarizes the vacuum.

Back to the equal time CCR (canonical commutation relation), which is roughly

\[[\phi(\vec{x}),\pi(\vec{x})]=i\delta^{3}(\vec{x}-\vec{x}'), \quad 0 \text{ otherwise.}\]Sometimes the field operator $\phi$ and $\pi$ are “smeared” in space, namely integrated against some controlled functions $f$

\[\phi(f) := \int d^{3}x \, f(\vec{x})\phi(\vec{x})\]so that quantities of interest are well defined. $f$ is called the test function. For example, we can smear the field to get rid of the Dirac delta function if necessary, and we get

\[[\phi(f),\pi(g)] = \left\langle f,g \right\rangle\]where $\left\langle f,g \right\rangle$ is the inner product of $f$ and $g$. Even though we are not gonna use this “regularized” commutation relation here, it is useful to know this trick.

Here should put a short mathematical explanation of the gist of Haag’s theorem.

HHW theorem does not imply that it’s impossible to treat interactions in the standard way (such as that adopted in Peskin&Schroeder), it just has to be unitarily inequivalent to the free Fock space. The HHW theorem shows that, a single, universal Hilbert space representation does not suffice for describing both free and interacting fields. Instead, unitarily inequivalent representations must be employed.

Put the example in $\phi^{4}_ {1+1}$ example by Jaffe.

With the reasons stated above, in our calculation we will adopt Schrodinger’s picture instead of standard interaction picture.

Vacuum sector of quantum theory

We will work in Schrodinger picture, where operators are dependent on position only. From time to time we will come back to interaction picture as a consistency check. We will only consider real scalar field $\phi$ in $d+1$ dimension. In Schrodinger picture, a generic operator $\mathcal{O}(\phi(\vec{x}),\pi(\vec{x}))$ is given as a function of the field $\phi(\vec{x})$ and the canonical momentum density $\pi(\vec{x})$, where $\vec{x}$ is the spatial coordinate. Note that since it is not the interaction picture, we don’t deal with the Lorentz covariant four-vector $x^{\mu}$.

Without loss of generality, we take phi-fourth theory for example, denoted $\phi^{4}_ {d+1}$. What we do to phi-fourth theory can be done to any potential. The Hamiltonian is normal ordered at mass scale $m_ {0}$, which is the bare mass of the free particle. Normal-ordering is regarded by me as a part of the definition of the theory, different people might have different views. Naturally people might ask, why normal order at the bare mass, not the renormalized mass $m$? Well, it doesn’t matter what mass scale we choose, after renormalization the ambiguity introduced by the mass scale is fixed by the renormalization conditions, and the observables are independent of this choice.

There is a $\mathbb{Z}_ {2}$ symmetry of the Hamiltonian which breaks spontaneously. The Hamiltonian before the Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking (SSB) reads:

\[\begin{align*} \hat{H}(\vec{x}) &= \int d^{d}x: \hat{\mathcal{H}}(\vec{x}) :_ {m_ {0}} \\ \hat{\mathcal{H}}(\vec{x}) &= \frac{1}{2}(\pi(\vec{x})^{2}+(\partial_ {i}\phi(\vec{x})^{2}) - \frac{1}{4}m_ {0}^{2}\phi^{2} + \frac{\lambda_ {0}}{4}\phi^{4}+A. \end{align*}\]We use the convention that parameters with a naught downstairs represent the bare parameters. $\hat{H}$ is the Hamiltonian before the spontaneous symmetry breaking (SSB).

To be more specific, the Hamiltonian undergoes spontaneous symmetry breaking since the minimum of the Hamiltonian is obtained at $\phi=\pm v_ {0}$ where $v_ {0}=\frac{m_ {0}}{\sqrt{2\lambda_ {0}}}$. Later we will shift the field operator from $\phi$ to $\phi’$, so that the vacuum is obtained at $\phi’=0$, the Hamiltonian in terms of $\phi’$ is denoted $H$ without hat. Note the factor $-m_ {0}^{2} /4$ in the mass term, we have $\frac{1}{4}$ instead of $\frac{1}{2}$ so that in the symmetry broken phase the particle has a canonical mass term. The last $A$ in the Hamiltonian is a c-number that cancels the zero point energy in the vacuum sector. We also define coupling $g_ {0}$ as

\[g_ {0}^{2} := \lambda_ {0}.\]The reason why we introduce a new symbol $g$ for $\sqrt{\lambda}$ is that, when we do calculations in the symmetry broken phase, we will be directly dealing with $\sqrt{\lambda}$ and define it to be $g$ just makes sense.

In the Schrodinger picture, the field operator and canonical momentum operator can be decomposed in terms of plane waves as usual,

\[\phi(\vec{x}) = \int \frac{d^{d}p}{(2\pi)^{d}} \, \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \omega_ {p} }} (a_ {p} \, e^{ i\vec{p}\cdot \vec{x} } + a^{\dagger}_ {p}\,e^{ -i\vec{p}\cdot \vec{x} }).\]The canonical commutation relation reads

\[[a_ {p},a^{\dagger}_ {k}] = (2\pi)^{d}\delta^{d}(\vec{p}-\vec{k}).\]But $a_ {p}$ and $a_ {p} ^{\dagger}$ are not Lorentz invariant, so we decided to introduce a Lorentz version:

\[\phi(\vec{x}) = \int \frac{d^{d}p}{(2\pi)^{d}} \, \frac{1}{2 \omega_ {p} } (A_ {p} \, e^{ i\vec{p}\cdot \vec{x} } + A^{\dagger}_ {p}\,e^{ -i\vec{p}\cdot \vec{x} }).\]The price to pay is that $A,A^{\dagger}$ no longer satisfy CCR. We can fix that by defining $A^{\ddagger}:= A^{\dagger} / 2\omega _ {p}$, then $A$ and $A^{\ddagger}$ satisfy CCR. In summary we have

\[\boxed{ \begin{align*} A_ {p} &\equiv \sqrt{ 2\omega_ {p} }\,a_ {p},\quad A^{\dagger}_ {p} \equiv \sqrt{ 2\omega_ {p} }\,a^{\dagger}_ {p}, \\ A^{\ddagger}_ {p} &:= \frac{A^{\dagger}_ {p}}{2\omega_ {p}} = \frac{a^{\dagger}_ {p}}{\sqrt{ 2\omega_ {p} }}, \\ [A_ {p},A^{\ddagger}_ {k}] &= (2\pi)^{d}\,\delta^{d}(\vec{p}-\vec{k}). \end{align*} }\]The renormalized quantities are define as

\[m^{2}=m_ {0}^{2} + \delta m^{2}, \quad \sqrt{ \lambda } = \sqrt{ \lambda_ {0} } + \delta \sqrt{ \lambda }.\]or equivalently

\[g = g_ {0} + \delta g.\]We also define $v$ to be the vev of $\phi$ in broken vacuum:

\[v = \frac{m}{\sqrt{ 2\lambda }} + \delta v.\]All the counter terms can be perturbatively expanded:

\[\begin{align*} \delta m^{2}& =\sum_ {i=1}^{\infty} \delta m^{2}_ {i} , \quad \delta m^{2}_ {i}\sim \mathcal{O}(g^{i+1}), \\ \delta g &= \sum_ {i=1}^{\infty} \delta g_ {i}, \quad \delta g_ {i} \sim \mathcal{O}(g^{i+2}),\\ H &= \sum_ {i=0}^{\infty} H_ {i},\quad H_ {i} \sim \mathcal{O}(g^{i-2}) , \\ A &= \sum_ {i=0}^{\infty}A_ {i}, \quad A_ {i} \sim \mathcal{O}(g^{i-2}) , \\ \delta v &= \sum_ {i=1}^{\infty} \delta v_ {i} ,\quad \delta v_ {i} \sim \mathcal{O}(g^{i}), \\ \left\lvert{\Psi}\right\rangle &= \sum_ {i=0}^{\infty} \left\lvert{\Psi_ {i}}\right\rangle , \quad \left\lvert{\Psi}\right\rangle _ {i} \sim \mathcal{O}(g^{i}), \\ I &\sim \mathcal{O}(g^{2}). \end{align*}\]Where $I$ is some variable which will be define later, I put it here for the sake of completeness.

Normal ordering revisited

Reference: Sidney Coleman’s 1975 paper and his lecture note title Aspects of Symmetry, the chapter about classical and quantum lumps.

In Coleman’s 1975 paper, he studied the sine-Gordon model

\[\mathcal{L} = \frac{1}{2} (\partial_ {\mu}\phi)^{2} + \frac{\alpha_ {0}}{\beta^{2}}\cos \beta \phi+\gamma_ {0}\]and famously pointed out:

- As for any theory of a scalar field with nonderivative interaction in 2 dimensional spacetime, normal ordering the Hamiltonian alone is enough to cancel all the divergences at any loop order;

- If the $\beta$-parameter exceeds $8\pi$, the Hamiltonian density is not bounded below.

- If $\beta<8\pi$, the model is equivalent to the charge-zero sector of almost-massive Thirring model.

- The fermion in the Thirring model is massless if $\beta=4\pi$.

Well, point 2,3 and 4 are not relevant to our discussion, I just put it here for the sake of completeness. My point is, turns out there is more to normal ordering than I thought. In textbooks such that by Peskin&Schroeder, or Mark Srednicki, normal ordering is regarded as a simple, if not trivial, ad hoc procedure that puts all the creation operators to the left of all the annihilation operators in order to eliminate the zero point energy of the trivial vacuum, and it was only done to the free part of the Hamiltonian. But when also applied to higher degree polynomial, the normal ordering can also generate counter terms. For example, normal ordering the $\phi^{4}$ term will generate a counter term for $\phi^{2}$ term. So I feel like it is necessary to revisit normal order.

The defining property of normal ordering is that expectation values of normal-ordered operators vanish in the free theory:

\[\left\langle{0}\right\rvert : \mathcal{O} :\left\lvert{0}\right\rangle =0\]for any operator $\mathcal{O}$ and free vacuum $\left\lvert{0}\right\rangle$. There are various formulations of this notion 1 , such as creation-annihilation operator normal ordering, conformal normal ordering, functional integral normal ordering, etc. In this note we will only talk about creation-annihilation operator normal ordering.

What is less often discussed is that normal ordering also depends on a mass scale mmm. In most cases, it is quite clear which value of mmm to choose, typically the mass of the free particle, known as the free mass. However, to determine what the free mass is, we first need to know the form of the Hamiltonian. For example if we can unambiguously separate the Hamiltonian into $\mathcal{H}_ {0}+U(\phi)$, where $\mathcal{H}_ {0}=\pi^{2} / 2+(\partial_ {x}\phi)^{2} /2+m^{2}\phi^{2} /2$, then $m$ is the free mass. Sometimes, however, the situation is more complex. For instance, it may be more convenient to include $m^{2}\phi^{2} /2$ in the interaction term, as in the case of sine-Gordon model. In this case, the free Hamiltonian only contains the kinetic part, and the free particle appears massless. In general, for a quadratic term of the form $a \phi^2$, where $a$ is a real parameter, we can choose how much of it goes into the free Hamiltonian, with the remainder contributing to the interaction. For example, we can pick a number such as $m_ {e}=0.511$ MeV and say that $m_ {e}^{2}\phi^{2}/2$ goes to the free Hamiltonian, such that the free particle has mass $m_ {e}$, then $(a-\frac{m^{2}}{2})\phi^{2}$ will go to the interaction. This is just a matter of convenience, the observables should not depend on such arbitrary choices.

So, how does all this relate to normal ordering? Normal ordering is a procedure that rearranges creation and annihilation operators, and these operators inherently depend on the free mass of the particle. $a^{\dagger}_ {p}$ creates a particle of momentum $\vec{p}$ with mass $m$, the energy of the particle is $\sqrt{ \vec{p}^{2}+m^{2} }$. I repeat, the choice of $m$ depends on what you choose to call the free Hamiltonian, and that choice is somehow arbitrary. The result of changing $m$ can be absorbed in a redefinition of the theory parameters.

My assumption is, the field operator $\phi(x)$ itself is independent of the aforementioned choice of mass parameter $m$, while the stuff that do depend on $m$ are

- creation and annihilation operators $a_ {p,m}$ and $a^{\dagger}_ {p,m}$,

- the energy $\omega=\sqrt{ \vec{p}^{2}+m^{2} }$, we will write it as $\omega_ {p,m}$ explicitly,

- states in Fock space. For example, the free vacuum $\left\lvert{0,m}\right\rangle$ is by definition annihilated by $a_ {p,m}$. Since the states in the Fock space are constructed by applying $a^{\dagger}_ {p,m}$ consecutively, a re-definition of $a^{\dagger}_ {p,m}$ to, say $a^{\dagger}_ {p,\mu}$ will also change the states themselves.

Recall that the field operator can be expanded in terms of energy and ladder operators,

\[\phi(\vec{x}) = \int \frac{d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{d}}\, \frac{1}{\sqrt{ 2\omega_ {k,m} }} (a_ {k,m} \, e^{ i\vec{k}\cdot \vec{x} } + a^{\dagger}_ {k,m}\,e^{ -i\vec{k}\cdot \vec{x} })\]and the $m$-dependence in $\omega_ {k,m}$, $a_ {k,m}$ and $a^{\dagger}_ {k,m}$ should cancel out so that $\phi(\vec{x})$ itself is $m$-independent.

We can define the normal ordering at $m$ by decomposing the Schrodinger picture fields and momenta into creation and annihilation part:

\[\begin{align*} \phi^{+}(\vec{x}) &= \int \frac{d^{3}p}{(2\pi)^{3}} \, e^{ -i\vec{p}\cdot \vec{x} } A^{\ddagger}_ {p,m} \\ \phi^{-}(\vec{x}) &= \int \frac{d^{3}p}{(2\pi)^{3}} \, e^{ i\vec{p}\cdot \vec{x} } \frac{A_ {p,m}}{2\omega_ {p,m}}, \end{align*}\]similarly for the canonical momenta

\[\pi^{\pm }(\vec{x}) = \pm i\sqrt{ -\nabla^{2}+m^{2} }\phi^{\pm }(\vec{x}) ,\]which implies

\[\begin{align*} \pi^{-}&= - \frac{i}{2} \int \frac{d^{3}p}{(2\pi)^{3}} \, e^{ i\vec{p}\cdot \vec{x} } A_ {p,m} ,\\ \pi^{+} &= i \int \frac{d^{3}p}{(2\pi)^{3}} \, e^{ -i\vec{p}\cdot \vec{x} } \omega_ {p,m}A^{\ddagger}_ {p,m} . \end{align*}\]It is easy to verify that

\[\begin{align*} \phi(\vec{x}) &= \phi^{+}(\vec{x}) + \phi^{-}(\vec{x}) , \\ \pi(\vec{x}) &= \pi^{+}(\vec{x}) + \pi^{-}(\vec{x}) . \end{align*}\]We can arrange a sting of field operators using the Wick’s theorem, which says that a string of product of field operators can be rewritten as the sum of all the possible contractions of operators, all of them normal ordered. For example,

\[\phi(\vec{x})\phi(\vec{x}) = :\phi(\vec{x})\phi(\vec{x}): + \text{ contraction}\left\lbrace \phi(\vec{x})\phi(\vec{x}) \right\rbrace .\]The contraction is where different choice of $m$ generates different results. Let’s write the contraction at $m$ as $C_ {m}\left\lbrace \cdots \right\rbrace$, we have

\[\boxed{ \begin{align*} \phi^{2}(\vec{x}) &= :\phi^{2}(\vec{x}):_ {m} + C_ {m}\left\lbrace \phi^{2}(\vec{x}) \right\rbrace , \\ C_ {m}\left\lbrace \phi^{2}(\vec{x}) \right\rbrace &= [\phi^{-},\phi^{+}] = \int \frac{d^3p}{(2\pi)^{3}} \, \frac{1}{2\omega_ {p,m}}. \end{align*} }\]Recall that $\phi^{2}$ is $m$-independent, while the normal ordering and the contraction are $m$-dependent. This gives us a means to connect normal ordering at different mass $m$ and $m_ {0}$, since

\[\phi^{2}(\vec{x}) = :\phi^{2}(\vec{x}):_ {m} + C_ {m}(\phi^{2}(\vec{x})) = :\phi^{2}(\vec{x}):_ {m_ {0}} + C_ {m_ {0}}(\phi^{2}(\vec{x})),\]which implies that

\[\begin{align*} :\phi^{2}(\vec{x}):_ {m_ {0}} &= :\phi^{2}(\vec{x}):_ {m} + C_ {m}-C_ {m_ {0}} \\ &= :\phi^{2}(\vec{x}):_ {m} + \frac{1}{2} \int \frac{d^{3}p}{(2\pi)^{3}} \, \left( \frac{1}{\omega_ {p,m}} - \frac{1}{\omega_ {p,m_ {0}}} \right) . \end{align*}\]where $C_ {m}$ is short for $C_ {m}(\phi^{2})$, a short-handed notation we will use extensively for the rest of the note. $C_ {m}$ is a c-number, usually given by a divergent integral.

Similarly, we can get normal order all the terms in the Lagrangian at all the mass scales. For details see my other notes.

If we start with a Hamiltonian normal ordered at $m_ {0}$, we can shift it to that normal ordered at the physical mass $m$, the difference is

\[\begin{align*} \hat{\mathcal{H}}(\vec{x})-\hat{\mathcal{H}}^{0}(\vec{x})&= \frac{3}{2}\lambda_ {0} I \phi^{2}(\vec{x}) + \frac{3}{4} \lambda_ {0} I^{2} - \frac{m_ {0}^{2}}{4}I \\ &\;\;\;\; + \frac{1}{4} \int \frac{d^{3}p}{(2\pi)^{3}} \, \left( \frac{2\vec{p}^{2}+m^{2}}{\omega_ {p,m}} - \frac{2\vec{p}^{2}+m_ {0}^{2}}{\omega_ {p,m_ {0}}} \right) \end{align*}\]where $\hat{\mathcal{H}}^{0}$ is normal ordered at $m_ {0}$.

Perturbative Expansion of the Hamiltonian

Since we want to cancel divergences in a perturbative manner, that is, order-by-order in (renormalized) coupling $\lambda$. When $\Lambda$ is involved, we should count the order with respect to $\lambda$ first, treating terms such as $\lambda \Lambda,\,\lambda \Lambda^{2}, \cdots\lambda \Lambda^{n}$ all as $\mathcal{O}(\lambda)$, and group things of the same order together. Only then do we take the limit $\Lambda\to\infty$, and cancel the divergences.

For the rest of this note, unless explicitly said otherwise, $\lambda$ stants for the renormalized coupling and $\lambda_ {0}$ the bare coupling.

I copy the Hamiltonian here:

\[\begin{align*} \hat{H}(\vec{x}) &= \int d^{3}x \, :\left\lbrace \hat{\mathcal{H}}^{0}(\vec{x}) + \frac{3}{2}\lambda_ {0} I \phi^{2}(\vec{x}) + \frac{3}{4} \lambda_ {0} I^{2} - \frac{1}{4}I\,m_ {0}^{2} \right\rbrace :_ {m} \\ &\;\;\;\; + \int d^{3}x \,\frac{1}{4} \int \frac{d^{3}p}{(2\pi)^{3}} \, \left( \frac{2\vec{p}^{2}+m^{2}}{\omega_ {p,m}} - \frac{2\vec{p}^{2}+m_ {0}^{2}}{\omega_ {p,m_ {0}}} \right) . \end{align*}\]A simple Taylor expansion shows that

\[\omega_ {p,m} = \omega_ {p,m_ {0}} + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\delta m^{2}}{\omega_ {p,m_ {0}}} + \mathcal{O}(\delta m^{4}),\]thus

\[\omega_ {p,m} - \omega_ {p,m_ {0}} \sim \mathcal{O}(\lambda)\]since $\delta m^{2}=(\cdots)\lambda+(\cdots)\lambda^{2}+\cdots$. Similarly,

\[\begin{align*} I &= \frac{1}{2} \int \frac{d^{3}p}{(2\pi)^{3}} \, \left( \frac{1}{\omega_ {p,m}}-\frac{1}{\omega_ {p,m_ {0}}} \right) \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \int \frac{d^{3}p}{(2\pi)^{3}} \, \left( - \frac{\delta m^{2}}{2 \omega^{3}_ {p,m_ {0}}} +\cdots \right)\\ &= -\frac{\delta m^{2}}{4} \int \frac{d^{3}p}{(2\pi)^{3}} \, \frac{1}{\omega^{3}_ {p,m_ {0}} } + \cdots\\ &\sim \mathcal{O}(\lambda) \end{align*}\]The last term in the Hamiltonian density reads

\[\frac{1}{4} \int \frac{d^{3}p}{(2\pi)^{3}} \, \left( \frac{2\vec{p}^{2}+m^{2}}{\omega_ {p,m}} - \frac{2\vec{p}^{2}+m_ {0}^{2}}{\omega_ {p,m_ {0}}} \right) = \frac{m_ {0}^{2}\delta m^{2}}{8} \int \frac{d^{3}p}{(2\pi)^{3}} \, \frac{1}{\omega^{3}_ {p,m_ {0}}} +\cdots.\]There is another constant term that is of order $\lambda$:

\[- \frac{1}{4}I\,m_ {0}^{2} = \frac{m_ {0}^{2}\,\delta m^{2}}{16}\int \frac{d^{3}p}{(2\pi)^{3}} \, \frac{1}{\omega^{3}_ {p,m_ {0}}} +\cdots.\]This is too bad, since I had hoped that the above equation will cancel the above above equation. But we can rearrange the terms proportional to $m_ {0}^{2}$ such that the integrals cancel each other and leaves us only one single term: $-\frac{3}{4} Im_ {0}^{2}$.

The term $\frac{3}{2}\lambda_ {0} I \phi^{2}(\vec{x})$ needs some extra work. It seems to be of order $\lambda_ {0}I\sim \mathcal{O}(\lambda^{2})$, however, often times we need to replace the field operator $\phi$ by $\left\langle \phi \right\rangle+\phi’$, where $\left\langle \phi \right\rangle$ is the expectation valued for $\phi$ under certain circumstances, and it is usually of order $\left\langle \phi \right\rangle\sim 1 / g$ where $g\equiv \sqrt{ \lambda }$. Thus this quadratic term is actually of order $\mathcal{O}(\lambda)$ and we need to keep it.

Putting everything together. At the leading order of $\lambda$ we have

\[\begin{align*} \hat{H}(\vec{x}) &= \int d^{3}x \, \left\lbrace :\hat{\mathcal{H}}^{0}(\vec{x}) + \frac{3}{2}\lambda_ {0} I \phi^{2}(\vec{x}) - \frac{3}{4} I m_ {0}^{2} :_ {m} \right\rbrace \end{align*}\]Then we write the bare parameters in terms of renormalized ones (recall that $g:= \sqrt{ \lambda }$ for both bare and renormalized parameters), at order $\mathcal{O}(\lambda)$ we have

\[\begin{align*} \hat{H}(\vec{x}) &\supset \int d^{3}x \, : \frac{1}{2}\pi^{2}+\frac{1}{2}(\partial_ {i}\phi)^{2} - \frac{m^{2}}{4}\phi^{2}+\frac{g^{2}}{4}\phi^{4}:_ {m} \\ &\;\;\;\; + \int d^{3}x \, : \frac{\delta m^{2}}{4}\phi^{2}-\frac{1}{2}g \delta g\phi^{4}+\frac{3}{2}g^{2}I\phi^{2}-\frac{3}{4}m^{2}I +A :_ {m}. \end{align*}\]We have neglected higher order terms, for example a term $3g\delta g\sim \mathcal{O}(g^{4}) \sim\mathcal{O}(\lambda^{2})$ was dropped from the expression.

Kink sector

Classic kink solution

Displacement operator

In order to find the approximate Hilbert state with correct vacuum expectation value of $\phi$, we introduce the displacement operator. Given a function $f(\vec{x})$, the associated displacement operator is defined as

\[\mathcal{D}_ {f} := \exp \left\lbrace -i\pi(f) \right\rbrace , \quad \pi(f):=\int d^{3}x \, f(\vec{x})\pi(\vec{x}).\]$\pi(f)$ is the smeared canonical momentum operator. This definition is similar to the space translation operator

\[T_ {\vec{x}} = \exp \left\lbrace -i\hat{P}\cdot \vec{x} \right\rbrace .\]The translation operator changes the position, while the displacement operator changes the vev of the field operator itself. In other words, $T_ {\vec{x}}$ translates in the configuration space, while $\mathcal{D}_ {f}$ translates in the function space. To be more specific, we have

\[[\phi(\vec{x}),\mathcal{D}_ {f}] = e^{ -i\pi(f) } [\phi(\vec{x}),-i\pi(f)] =f(\vec{x}) \mathcal{D}_ {f},\]hence

\[\mathcal{D} \phi \mathcal{D}^{\dagger}=\phi-f.\]Since $\mathcal{D}_ {f}^{-1}=\mathcal{D}_ {-f}$, we have the following comparison:

\[\begin{align*} T_ {\vec{x}}^{\dagger}\, \phi(\vec{y})\, T_ {\vec{x}} &= \phi(\vec{y}+\vec{x}),\\ \mathcal{D}_ {f} ^{\dagger} \, \phi(\vec{x})\, \mathcal{D}_ {f} &= \phi(\vec{x})+f(\vec{x}). \end{align*}\]The point is that we can use the unitary $\mathcal{D}_ {f}$ to translate the basis of the Hilbert space.

Compare $T_ {\vec{x}}$ and $\mathcal{D}_ {f}$. Let $\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle$ be any state, the resulting state of $T_ {\vec{x}}$ acting on $\left\lvert \psi \right\rangle$, namely the state $T_ {\vec{x}}\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle$, has two interpretations: the passive view and the active view. In the passive view, the translation is seen as a change to the coordinate system or reference frame, rather than a change to the state itself. The state of the system remains unchanged, but the coordinates used to describe it are shifted. In contrast, in the active view, the translation actively shifts the state, while the coordinate system remains the same. The coordinates stay fixed, but the state (or field configuration) changes.

The same applies to the displacement operator $\mathcal{D}_ {f}$, given any state (now we are working in the context of quantum field theory, rather than quantum mechanics) $\left\lvert{\Psi}\right\rangle$, $\mathcal{D}_ {f}\left\lvert{\Psi}\right\rangle$ can be interpreted either as a new state (active perspective), or as the same state but in different basis (passive perspective).

When it comes to the discussion about kink states and trivial vacuum states, my personal taste is to think of $\mathcal{D}_ {f}$ passively. This approach allows us to discuss the same states in different bases, or “frames”.

$\mathcal{D}_ {f}$ “shifts” $\left\lvert{\varphi}\right\rangle$ by $f(\vec{x})$ as

\[\mathcal{D}_ {f}\left\lvert{h(\vec{x})}\right\rangle = \left\lvert{h(\vec{x})+f(\vec{x})}\right\rangle .\]As you can verify, we also have

\[\left\langle{\Psi}\right\rvert \mathcal{D}_ {f}^{\dagger} \hat{\phi}(\vec{x}) \mathcal{D}_ {f}\left\lvert{\Psi}\right\rangle = \psi(\vec{x})+f(\vec{x}),\]as we showed before. We can regard $\mathcal{D}_ {f}\left\lvert{\Psi}\right\rangle$ as the same state as $\left\lvert{\Psi}\right\rangle$, just measured with different basis: instead of $\left\langle \varphi \middle\vert \Psi \right\rangle$, we have $\left\langle \varphi+f \middle\vert \Psi \right\rangle$.

From the expansion

\[\phi(\vec{x}) = \int \frac{d^{d}p}{(2\pi)^{d}\sqrt{2\omega_ {p}}} \, (a_ {p} e^{ i\vec{p}\cdot \vec{x} }+h.c.)\]and $\mathcal{D}\phi \mathcal{D}^{\dagger}=\phi-f$, we can determine how $\mathcal{D}$ sandwiches $a_ {p}$:

\[\mathcal{D}_ {f} a_ {p} \mathcal{D}_ {f}^{\dagger} = a_ {p} - \widetilde{a}_ {p}\]where $\widetilde{a}$ is the coefficient of the kink solution,

\[f(\vec{x}) = \int \frac{d^{d}p}{(2\pi)^{d}\sqrt{2\omega _ {p} }} \, (\widetilde{a}_ {p}e^{ i\vec{p}\cdot \vec{x} }+\widetilde{a}_ {p}^\ast e^{ -i\vec{p}\cdot \vec{x} }) .\]Field operator in the kink sector

In the language of Lagrangian or path integral, perturbation method is relatively straightforward. Consider the scalar $\phi^{4}$ theory with spontaneous symmetry breaking,

\[\mathcal{L} = \frac{1}{2} (\partial_ {\mu}\phi)^{2} + \frac{1}{4} m^{2} - \frac{\lambda}{4}\phi^{4}.\]After the spontaneous symmetry breaking the vacuum is shifted from $\left\langle \phi \right\rangle=0$ to $\left\langle \phi \right\rangle= m / \sqrt{2\lambda}$. Now, we want to study the quantum fluctuation of real scalar field $\phi$ in the back ground $\phi=\frac{m}{\sqrt{2\lambda}}$, what we do is redefine the field operator as $\phi\to \frac{m }{\sqrt{ 2\lambda }}+\phi’$, so that the new vacuum is obtained at $\phi’$ equals zero. We treat $\phi’$ as the fundamental quantum field. The small fluctuation about $\frac{m }{\sqrt{ 2\lambda }}$ gives the quantum effects via partition function

\[Z[J] = \int D\phi' \, \exp \left\lbrace iS[\phi']+i \int \phi' J \right\rbrace ,\]about $\phi’\sim 0$. We say that this partition function is perturbative about $\phi’=0$.

Above is in Lagrangian formalism, we know there is also Hamiltonian formalism, and anything that can be done with one formalism can equally be done in the other, it is just a matter of convenience.

The fundamental idea is similar to the perturbative calculation we did in quantum mechanics, but generalized to quantum field theory. The key idea is that to perform the perturbation calculation about a state $\left\lvert \Psi \right\rangle$, we need to find the basic field operator $\phi’$ that has zero vev, $\left\langle \Psi \right\rvert\phi’\left\lvert \Psi \right\rangle=0$. Then and only then can we apply the standard perturbation method to $\phi’$ and $\left\lvert \Psi \right\rangle$.

Turns out, the desired basic field operator $\phi’$ differs from the original field operator just by an unitary transformation, given by the displacement operator. Recall the defining property of displacement operator, $\mathcal{D}_ {f}^{\dagger}\phi \mathcal{D}_ {f}=\phi+f$.

Let’s start with a trivial case. We know that the phi fourth model admits SSB. Assume we want to perform perturbative calculation in the symmetry broken phase $\left\lvert 0^{+} \right\rangle$, where the original field operator $\phi$ has vev $\left\langle 0^{+} \right\rvert \phi \left\lvert 0^{+} \right\rangle=-v$, where

\[v = -\frac{m }{\sqrt{ 2\lambda}}.\]Use the displacement operator to transform $\phi$, we have (at least at leading order)

\[\left\langle{0^{+}}\right\rvert \mathcal{D}_ {v }^{\dagger} \phi \mathcal{D}_ {v }\left\lvert{0^{+}}\right\rangle = \left\langle{0^{+}}\right\rvert \phi+v \left\lvert{0^{+}}\right\rangle = \frac{m }{\sqrt{ 2\lambda }}-\frac{m }{\sqrt{ 2\lambda }}=0,\]hence

\[\boxed{ 0=\left\langle{0^{+}}\right\rvert \phi'\left\lvert{0^{+}}\right\rangle, \quad \phi':= \mathcal{D}_ {v }^{\dagger}\phi \mathcal{D}_ {v }. }\]It inspires us to define a new Hamiltonian exactly in the same fashion,

\[\boxed{ \mathcal{H} := \mathcal{D}_ {v }^{\dagger} \hat{\mathcal{H}} \mathcal{D}_ {v }=\hat{\mathcal{H}}(\mathcal{D}^{\dagger}\phi \mathcal{D}) = \hat{\mathcal{H}}(\phi'). }\]We are interested in the spectrum of the Hamiltonian. The good news is that, a unitary transformation preserves all the observables! Thus, in order to study the quantum correction, instead of working with the triplet $\hat{H}$, $\phi$ and $\left\lvert{0^{+}}\right\rangle$ where perturbative method fails, we can work with $H, \phi’$ and $\left\lvert{0^{+}}\right\rangle$ where $\phi’$ can be dealt with perturbatively.

Generally speaking, let $\mathcal{O}$ be any operator and $\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle$ its eigenstate. If $\mathcal{O}’=\mathcal{D}^{\dagger}\mathcal{O} \mathcal{D}$ is the unitary transformation of $\mathcal{O}$, then its eigenstate is $\mathcal{D}^{\dagger}\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle$, not $\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle$. It may seem weird to some people to put $\mathcal{O}’$ together with $\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle$ rather than $\mathcal{D}^{\dagger}\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle$. In fact, it is exactly the point of our method! If we pair $\mathcal{O}’$ with $\mathcal{D}^{\dagger}\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle$ it would be a trivial transformation, we will get nothing new! Paring up $\mathcal{O}’$ and $\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle$ makes it possible for perturbation methods.

However, since $\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle$ is not the eigen state of $\mathcal{O}’$, it indeed raise some troubles, the first and foremost is that now $\mathcal{O}’$ is in general not diagonalized by $\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle$, we need to find a way to diagonalized it. In our current case, since the displacement operator only shifts the operators by a constant, it actually preserves the diagonalization, meaning if $\hat{\mathcal{H}}$ is diagonalized in $\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle$’s then $\mathcal{D}^{\dagger} \hat{\mathcal{H}}\mathcal{D}$ is also diagonalized in $\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle$’s. But for a generic $\mathcal{D}_ {f}$ with non-trivial $f$, this will no longer be true. That would be the topic for the other half the the note, after we introduce the kink solution.

A comparison between displacement operator method to the case of regular functions might be helpful.

| Functions | perturbative QFT |

|---|---|

| A functions $f(x)$, a neighborhood about a special locus $x_ 0$ where the interesting things happen. | A Hilbert space, a quantum state $\left\lvert{\Psi}\right\rangle$ of interest represented by a functional $\left\langle \Psi(x),- \right\rangle$, and some operator $\mathcal{O}(\phi)$. |

| We want to study the function $f(x )$ at $x_ 0$ perturbatively, | We want to study the $\left\langle{\Psi}\right\rvert\mathcal{O}\left\lvert{\Psi}\right\rangle$ perturbatively, |

| but $x_ 0$ too far from the origin, so Maclaurin expansion (Taylor expansion at the origin) fails. | but $\left\langle{\Psi}\right\rvert\phi \left\lvert{\Psi}\right\rangle=:f(x)$ is too large for $\phi$ to be treated perturbatively. |

| In a passive perspective, we shift the origin to $x_ 0$, then small deviation from $x_ 0$ can now be studied using Maclaurin expansion perturbatively. | In a passive perspective, we shift the operators, especially the field operator $\phi$ since it is usually the building block of other operators. The expectation value of the new, shifted operator $\phi’$ should be zero, $\left\langle{\Psi}\right\rvert \phi’\left\lvert{\Psi}\right\rangle =0$. Now we can treat $\phi$ perturbatively. |

| Shifted coordinate system to study the same old functions $f(x)$. | Shifted operators $\mathcal{D}^{\dagger}\mathcal{O}\mathcal{D}$ to study the same old states $\left\lvert{\Psi}\right\rangle$. |

In summary, $\mathcal{H}=\mathcal{D}^{\dagger}_ {v}\hat{\mathcal{H}}\mathcal{D}_ {v}$ is a operator-valued function of $\phi’ = \mathcal{D}_ {v}^{\dagger} \phi \mathcal{D}_ {v}$, and $\phi’$ can be dealt with perturbatively.

Now let’s apply this go kink background. Denote the generic kink solution as $f(\vec{x})$ in $d$ dimensional space, let the kink state be $\left\lvert K \right\rangle$ and the original field operator be $\phi$. We have

\[\left\langle K \right\rvert \phi(\vec{x}) \left\lvert K \right\rangle = f(\vec{x})\]at the leading order. In general $f(\vec{x})$ is inversely proportional to the coupling, for example for $\phi^{4}$ model we have $f\propto 1 / \sqrt{\lambda}$.

Denote the perturbative field operator in the kink sector as $\varphi$, it should satisfy

\[\left\langle K \right\rvert\varphi \left\lvert K \right\rangle=0.\]Since $\left\langle K \right\rvert\phi \left\lvert K \right\rangle=f$, at least at the leading order we should have

\[\boxed{ \varphi = \mathcal{D}_ {f} \phi \mathcal{D}^{\dagger}_ {f}, }\]we will neglect the subscript $f$ is it is clear from the context.

As you can easily check, the kink field operator $\varphi$ satisfies the same commutation relation with $\mathcal{D}$ as $\phi$:

\[[\varphi,\mathcal{D}_ {f}] = f\, \mathcal{D}_ {f}.\]If we write the same Hamiltonian (note that it has to be the same Hamiltonian no matter what perturbative basic field we choose to use, otherwise we would be solving a different problem) in terms of $\varphi$, we have

\[H[\phi] = H[\mathcal{D} \varphi \mathcal{D}^{\dagger}] = \mathcal{D}H[\varphi]\mathcal{D}^{\dagger} =: H'[\varphi].\]Things to put here: Define the free (quadratic) Hamiltonian of kink Hamiltonian.

Assume the kink $f(x)$ as a static, classical background, about which we expand the field operator as fluctuation. Write the fluctuation as $\mathfrak{g}(x,t)$ and assume that we can separate the time ans position coordinates,

\[\phi(x,t) =: f(x) + {\mathfrak g}(x) e^{-i\omega t},\]The equation of motion of ${\mathfrak g}$ reads

\[[-\omega^{2}-\partial_ {x}^{2}+V^{(2)}(\sqrt{ \lambda }f(x))]\, {\mathfrak g}(x) = 0,\]Which is the Sturm-Liouville equation. A general Sturm-Liouville problem is typically written in the form:

\[\frac{d}{dx}\left[ p(x) \frac{dy}{dx} \right] - q(x)y + \lambda r(x)y = 0\]Here, $y$ is the function of the variable $x$ that we are solving for, and $p(x)$, $q(x)$, $r(x)$ are known functions that specify the particular Sturm-Liouville problem. The parameter $\lambda$ is often referred to as the eigenvalue.

A few more words on the equation. Key characteristics and applications of the Sturm-Liouville equation include:

-

Eigenvalue Problem: The Sturm-Liouville equation is an eigenvalue problem. The solutions $y(x)$ are eigenfunctions, and the associated values of $\lambda$ are eigenvalues. These eigenvalues are typically discrete and can be ordered as a sequence $\lambda_1, \lambda_2, \lambda_3, \ldots$, where each $\lambda_n$ corresponds to a particular eigenfunction $y_n(x)$.

-

Orthogonality and Completeness: The eigenfunctions of a Sturm-Liouville problem are orthogonal with respect to the weight function $r(x)$. This property is crucial in solving partial differential equations, as it allows the expansion of functions in terms of these eigenfunctions (similar to Fourier series).

-

Boundary Conditions: Sturm-Liouville problems are typically accompanied by boundary conditions that the solutions must satisfy. These conditions are usually specified at the endpoints of the interval in which the equation is defined.

In our case, the weight function is trivial.

We will denote the zero mode (eigenfunction with eigenvalue zero) by ${\mathfrak g}_ {B}$ and the shape mode (the next level up to zero mode) by ${\mathfrak g}_ {S}$. The $B$ in ${\mathfrak g}_ {B}$ has a historical reason (B stands for bounded state), but in our note it is just part of the name. These modes include a continuum

\[{\mathfrak g} _ {k}(x) = \frac{e^{-ikx}}{\omega_ {k} \sqrt{m^2+4k^2}}\left[2k^2-m^2+(3/2)m^2\text{sech}^2(m x/2)-3im k\tanh(m x/2)\right]\]with eigenvalue $\omega_ {k} = \sqrt{ k^{2}+m^{2} }$, a zero mode

\[{\mathfrak g}_ {B} = -\sqrt{ \frac{3m}{8} } \text{sech}^{2}\left( \frac{mx}{2} \right)\]with eigenvalue $0$, and a shape mode

\[{\mathfrak g} _ {S} = \frac{\sqrt{ 3m }}{2} \tanh \frac{mx}{2} \text{sech} \frac{mx}{2},\quad \omega_ {S} = \frac{\sqrt{ 3 }}{2}m\]with eigenvalue less then the rest mass of excited particle.

The normalization conditions are

\[\int dx \, {\mathfrak g}_ {S}^{2} = \int dx \, {\mathfrak g}_ {B}^{2} = 1 , \quad \int dx \, {\mathfrak g}_ {B}{\mathfrak g}_ {S} = 0 ,\quad \int dx \, {\mathfrak g}_ {k}(x){\mathfrak g}_ {p}(x) = 2\pi i\delta(p-k).\]The completion condition reads

\[\sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \; \frac{dk}{2\pi} \, \mathfrak{g} _ {k} (x)\mathfrak{g} _ {k} ^\ast (y)=\delta(x-y).\]and $\mathfrak{g}_ {k}^\ast(x)=\mathfrak{g}_ {-k}(x)$.

The sign of ${\mathfrak g}_ {B}$ is fixed using

\[{\mathfrak g}_ {B}(x) = - \frac{f'(x)}{\sqrt{ Q_ {0} } },\]where $f$ is again the kink solution.

This can be generalized to more than one spatial dimension. Take two dimension for example, without loss of generality, we can choose to lie the kink in the $x$ direction.

The important thing is that, the free kink Hamiltonian is diagonalized by normal mode. what I mean is that, if we expand the kink field in terms of normal modes:

\[\begin{align*} \varphi(x) &= \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \frac{ dk}{(2\pi )\sqrt{2\omega _ {k} } } \, \left( b_ {k} {\mathfrak g}_ {k} (x)+h.c. \right),\\ \pi(x) &= \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \frac{dk}{(2\pi ) } \frac{-i\sqrt{\omega_ {k}}}{\sqrt{2}}\, \left( b_ {k}\mathfrak{g}_ {k} (x) - b_ {k}^{\dagger}\mathfrak{g}_ {k} ^\ast (x) \right){\mathfrak g}_ {k} (x), \end{align*}\]where

\[\sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \, dk := \sum_ {B,S}+\int \frac{dk}{2\pi}.\]it can be verified that

\[[b_ {k} ,\mathcal{D}_ {f}] = \mathcal{D}_ {f} \frac{\mathfrak{f} _ {k}+\mathfrak{f} _ {-k}^\ast }{2},\]where $\mathfrak{f}_ {k}$ is the coefficient in spanning $f(x)$ in terms of $\mathfrak{g}_ {k}(x)$:

\[f(x)=\sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \; \frac{dk}{2\pi} \, \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\omega _ {k} }}(\mathfrak{f} _ {k} \mathfrak{g} _ {k} (x)+\text{c.c.}),\]where c.c. stands for complex conjugation. From this commutation relation we can see that if $\left\lvert 0 \right\rangle$ is a state annihilated by $b_ {k}$, then $\mathcal{D}_ {f}\left\lvert 0 \right\rangle$ is a coherent state regarding $b_ {k}$ since

\[b_ {k} \mathcal{D}_ {f}\left\lvert 0 \right\rangle = \mathcal{D}_ {f}\mathcal{D}_ {f}^{\dagger}b_ {k} \mathcal{D}_ {f} \left\lvert 0 \right\rangle= \mathcal{D}_ {f}(b_ {k} +(\cdots))\left\lvert 0 \right\rangle =(\cdots) \mathcal{D}_ {f}\left\lvert 0 \right\rangle,\]where $(\cdots)=\frac{\mathfrak{f} _ {k}+\mathfrak{f} _ {-k}^\ast }{2}$ is a c-number.

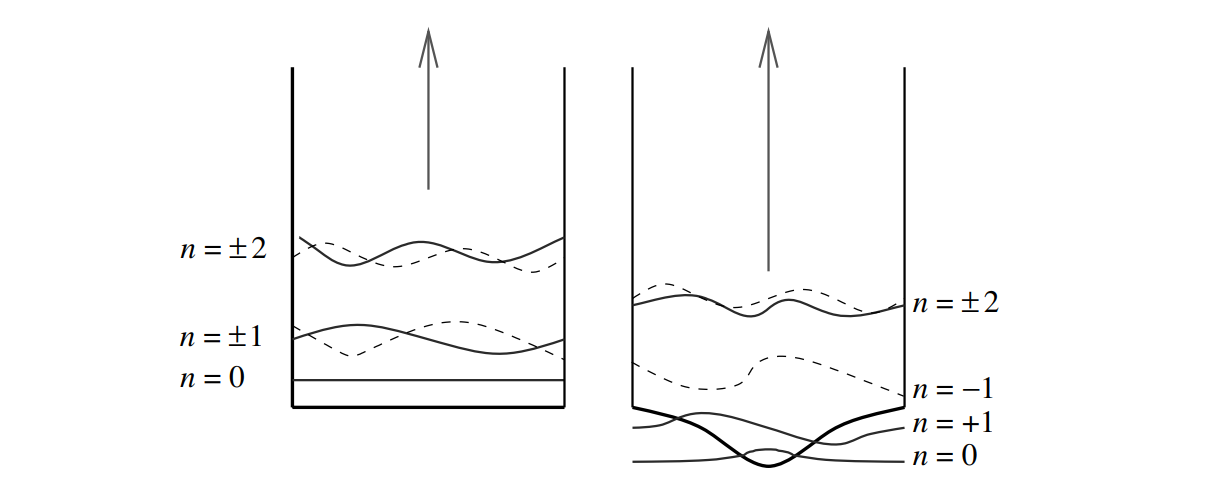

in normal modes (in the kink background), while expanding in the $y$ direction in plane waves. The 2D momentum is $\vec{k}=\left\lbrace k_ {x},k_ {y} \right\rbrace$, where $k_ {x}=\left\lbrace B,S,k \right\rbrace$, $B$ for the zero mode (bounded solution), $S$ for the shape mode (also bounded) and $k$ for the continuum. A nice illustration of normal modes in the background of kink is shown in the figure below, which I shamelessly copied from Tanmay Vachaspati’s book, all the credits goes to Vachaspati.

We have omitted the vector sign (or bold font) in $r$ since it would not cause any misunderstanding. We assume (quite reasonably) the separation of variables $x$ and $y$ for 2D normal modes ${\mathfrak g}(r)$,

\[{\mathfrak g}(r) = {\mathfrak g}_ {x}\times g_ {y},\quad {\mathfrak g}_ {x} = \text{kink normal modes},\, {\mathfrak g}_ {y} = \text{plane waves.}\]The quantization in terms of $\phi$ and $\pi$ reads

\[[\phi(r),\pi(r')] = i\delta^{(d)}(r-r').\]This represents the fundamental quantization relation, unaffected by the selection of sectors. We haven’t given a formal definition of sectors, roughly speaking, within each sector, there exists a distinct set of normal modes for expanding both $\phi$ and $\pi$. Each mode must conform to the aforementioned relation, namely the quantization relation given in space-time positions $r$. Ultimately, the difference across different sectors lies in the diverse backgrounds (regarded as classical functions) used for field expansion. However, as we are analyzing the same theory within the same space-time, the theory should be quantized only once, and, all sectors must consistently align with the same quantization process.

Need for a new set of ladder operators

Squeeze!

Linearized soliton perturbation method (LSPT)

Here we summarize the linearized soliton perturbation theory associated with generic solitonic classic solutions $f_ {\text{sol}}$

Appendix

Loop expansion, semi-classical expansion and coupling expansion

There are three different but expansions that we usually don’t extinguish:

- Loop expansion, the expansion parameter is the number of loop. The leading contributions are tree diagrams.

- Semi-classical expansion, the expansion parameter is the Plank constant $\hbar$. At leading order, $\hbar=0$, we are left with classical contributions.

- Coupling expansion, the expansion parameter is the coupling $g,\lambda, \cdots$.

Set the speed of light $c=1$. The action functional $S[\phi]$ has the unit of $[\hbar]=ET$, where $E$ is the energy unit and $T$ the time. The textbook proof of the equivalence between loop expansion and semi-classical expansion, i.e. $\hbar$-expansion usually goes as follows. First write the partition function (with the source term) with $\hbar$:

\[Z[J(x)] = \int \mathcal{D}\phi \, \exp \left\lbrace \frac{i}{\hbar} \int d^{d}x \, (\mathcal{L}+ J \phi) \right\rbrace ,\]where $J=J(x)$ is the source term. Note that the source term is on the same basis of $\mathcal{L}$. Splitting the Lagrangian into free and interacting part, we can rewrite the interaction using functional derivative and put it in the front of the free partition function:

\[Z[J] = \exp \left\lbrace \frac{i}{\hbar}\mathcal{L}_ {\text{int}}\left( \frac{1}{i} \frac{\delta}{\delta J} \right) \right\rbrace Z_ {0}[J],\]where $\mathcal{L}_ {\text{int}}$ is the interacting Lagrangian and

\[Z_ {0}[J] = \int \mathcal{D}\phi \, \exp \left\lbrace \frac{i}{\hbar}\int d^{d}x\, (\mathcal{L}_ {0}+ J\phi) \right\rbrace\]is the free partition function with the source. It can be integrated out in the closed form (for the level of rigorous for a physicist) to give

\[Z_ {0}[J] = N \exp \left\lbrace - \frac{i}{2}\hbar \int d^{d}x d^{d}y \, J(x) \Delta_ {F}(x-y)J(y) \right\rbrace,\]where $\Delta_ {F}$ is the Feynman propagator. It shows that each propagator contributes a factor of $\hbar$.

Next, since each diagrammatic vertex is a result of a functional derivative $\frac{i}{\hbar }\mathcal{L}_ {\text{int}}\left( \frac{\delta}{\delta J} \right)$, each vertex contributes a factor of $\frac{1}{\hbar}$. Then, using some relations between the numbers of loops, propagators and vertices (it depends on the specific model), amputate the external legs, it can be shown that: a general graph with $L$ loops is proportional to $\hbar^{L-1}$. Thus an expansion in the number of loops is also an expansion in powers of $\hbar$.

It turns out that there are more than one way to assign $\hbar$-dependence to parameters in the Lagrangian, such as mass $m$, the coupling $g,\lambda$, etc. A criterion for the “right” choice is that, at $\hbar\to 0$, the quantum theory agrees with the classical theory. As an example, Stanley Brodsky and Paul Hoyer in their paper used the quantum mechanical harmonic oscillator as an example in Eq.(1). The gist is that you can rescale $x$ to $x / \sqrt{ \hbar }$, then the propagator is formally independent of $\hbar$. However, this will change how we view distance, in the $\hbar\to 0$ limit, for a fixed distance $L$, the “length” measure will increase as $1 / \sqrt{ \hbar }$, hence we are going to smaller and smaller area.

It is generally understood that each loop contribution to amplitudes is associated with one factor of $\hbar$. However, to fully define the $\hbar\to 0$ limit one need to specify the $\hbar$ dependence of various quantities in the Lagrangian as mentioned before, such as the field operator, the mass, the coupling, etc. This is not as straightforward as one might think, for $\hbar$ not only appears in the action $iS / \hbar$ but also appears in the Lagrangian. In Brodsky’s paper mentioned above, the authors proposed a way to establish the $\hbar$ dependence such that the loop and $\hbar$ expansions are equivalent. We will go to more details in the following.

First, regard $\hbar$ as a constant of nature with certain dimension, use $\hbar$ to make terms in the Lagrangian dimensionless.

Again let’s work with the assumption that $c = \epsilon_ {0} = 1$. Require $[S]=\hbar$, and $\alpha_ {s} = g^{2} / 4\pi \hbar$ is dimensionless, the latter implies that $[g]=[\sqrt{ \hbar }]=\sqrt{ ET }=\sqrt{ EL }$. From the self-energy of gluons $G_ {\mu \nu}G^{\mu \nu}$ where $G = \partial A - \partial A +ig / \hbar [A,A]$ we have

\[[A] = \sqrt{ \frac{E}{L} }.\]Similarly, in scalar QED model the classical electric charge $e$ and mass $m$ are divided by $\hbar$,

\[S_ {\text{sQED} } = \int d^{4}x \, \left\lbrace \left\lvert D\phi \right\rvert ^{2}-\frac{m^{2} }{\hbar^{2} }\left\lvert \phi \right\rvert ^{2} \right\rbrace , \quad D = \partial +i \frac{e}{\hbar }A.\]The boson field dimension

\[[\phi]=[A]= \sqrt{ \frac{E}{L} }.\]Fermion fields are more complicated, since they have no classical counterparts, their dimensions are convention-dependent. We will deal with fermions in a different note perhaps.

Second step is to specify $\hbar$ dependence of all quantities appearing in the action.

The choice made by Brodsky and Hoyer is as following. Define

\[\widetilde{A}:= \frac{A}{\sqrt{ \hbar } },\quad \tilde{\phi}:= \frac{\phi}{\sqrt{ \hbar } }\]where $\widetilde{A},\tilde{\phi}$ are $\hbar$-independent. Similarly, define the following $\hbar$-independent quantities

\[\widetilde{g}:= \frac{g}{\hbar},\quad \widetilde{e}:= \frac{e}{\hbar},\quad \widetilde{m}:= \frac{m}{\hbar}.\]Then one can write the Lagrangian in terms of these $\hbar$-independent quantities to check the $\hbar$ dependence explicitly. It turns out that, at least in the simple models discussion in the paper, $\hbar$ always appears in the combination

\[\widetilde{g}\sqrt{ \hbar } \quad \text{and}\quad \widetilde{e}\sqrt{ \hbar }\]that is, with the coupling. Hence loop correction of $\mathcal{O}(g^{2},e^{2})$ will be of order $\hbar$.

This derivation is equivalent to the standard textbook treatments, for example in Mark Srednicki’s textbook, which associates a factor $\hbar$ to each propagator and $h^{-1}$ with each vertex, and assume that the parameters appearing in the action are independent of $\hbar$.

Fore more details refer to Brodsky and Hoyer’s paper mentioned above. The takeaway is that, the correspondence between loop expansion and $\hbar$ expansion is widely accepted, taken for granted, but convention dependent.

The semi-classical approximation is also a result of small fluctuation about certain classical background. This can be seen from the Steepest descent method. For an amazing introduction, see chapter 6 of the book by Carl Bender and Orszag Advanced Mathematical Methods for Scientists and Engineers I. The gist is that the integral can be approximated by an asymptotic power expansion, the leading term is given by its stationary value:

where $x_ {0}$ is the stationary point and $A(\hbar)$ is an asymptotic power series in $\hbar$,

\[A(\hbar) = 1+A_ {1} \hbar + A_ {2} \hbar^{2} + \cdots\]which, being an asymptotic series, eventually diverges. The coefficients, $A_ {1}, A_ {2}$, etc, can be calculated using loop expansion.

Some Mathematical Preliminaries

An algebra over a field $k$ is a vector space $A$ over $k$, equipped with an additional structure: a bilinear multiplication $\cdot: A \times A \to A$ that makes $A$ a ring (not necessarily commutative). That is, $A$ has:

- Addition $+$ and scalar multiplication $\cdot$, making $A$ a $k$-vector space,

- A bilinear multiplication satisfying associativity.

More formally, an algebra $A$ is a vector space over field $k$ together with a map:

\[\mu: A \times A \to A, \quad (a, b) \mapsto ab\]that satisfies the ring axioms and is $k$-bilinear, meaning:

\[(ab + c)d = ab \cdot d + c \cdot d, \quad a(b + c)d = ab \cdot d + ac \cdot d\]for all $a, b, c, d \in A$. Examples of Algebras include Matrix algebra (the space of $n \times n$ matrices over a field $k$, with matrix addition and multiplication), Polynomial algebra and Function algebra.

An algebra $A$ is said to be unital if it contains a multiplicative unit $1$.

Denote by $\mathcal{E}$ a complex Hilbert space, with inner product $\left\langle - \middle\vert- \right\rangle$, and $\mathcal{B}(\mathcal{E})$ the set of all bounded operators. In is a Banach algebra with the operator norm, which is defined as

Let $\xi_ {1},\xi_ {2} \in\mathcal{E}$. For $a\in \mathcal{B}(\mathcal{E})$, the adjoint operator $a^{\ast}$ is defined by

\[\left\langle a^{\ast }\xi_ {1} \middle\vert\xi_ {2} \right\rangle = \left\langle \xi_ {1} \middle\vert a \xi_ {2} \right\rangle .\]The adjoint operation is an involution, i.e. it is anti-linear (meaning $(\lambda a)^{\ast}=\overline{\lambda} a^{\ast}$, where $\overline{\lambda}$ is the complex conjugate of $\lambda$) and satisfies $(ab)^{\ast}=b^{\ast}a^{\ast}$.

For it to be a $\mathbb{C}^{\ast}$-algebra, it must satisfy the $\mathbb{C}^{\ast}$-identity

\[\left\lVert a^{\ast }a \right\rVert = \lVert a \rVert ^{2}.\]If the $\mathbb{C}^{\ast}$-algebra is Cauchy-complete under the operator norm, then it is said to be a concrete $\mathbb{C}^{\ast}$-algebra. By default all the $\mathbb{C}^{\ast}$-algebras we talk about will be concrete, so we will ignore it.

A module over an algebra $A$ is a generalization of a vector space, where the scalars used for multiplication come from the algebra $A$ rather than a field. Te be precise, an $A$-module $M$ is an abelian group (under addition) together with a multiplication map:

satisfying the following conditions for all $a, b \in A$, $m, n \in M$, and $\lambda \in k$:

- Distributivity: $(a + b) \cdot m = a \cdot m + b \cdot m$,

- $a \cdot (m + n) = a \cdot m + a \cdot n$,

- $(\lambda a) \cdot m = \lambda (a \cdot m)$,

- $(ab) \cdot m = a \cdot (b \cdot m)$.

Roughly speaking, a vector space is just a module over a field. A module over a commutative algebra $A$ can be thought of as a generalization of a vector space where scalars come from $A$ instead of $k$.

Examples of modules over algebras include Module over matrix algebras, Polynomial modules, etc.

A module is said to be simple if it does not have nonzero proper submodule.

Definition. Endomorphism algebra. If $V$ is a $k$-vector space, then $\text{End}(V)$ is an algebra formed of the the set of all linear maps from $V$ to $V$ itself (endomorphisms), where the multiplication of two elements is given by composition.

For example, let $V$ be $\mathbb{R}^{n}$, then the endomorphism algebra $\text{End}(V)$ is the $n\times n$ real matrices.

Definition. Algebra representation. Let $A$ be a $k$-algebra, a representation of $A$ is a homomorphism between algebras that maps $A$ to $\text{End}(V)$ for some $k$-module $V$.

In human’s language, to define a representation of an abstract algebra, we first choose a module that the algebra act on, then define how exactly each element of the algebra acts on $V$.

An introduction of category theory can be found in my blogs here and here. A blog explicitly devoted to Yoneda lemma which is sometime useful in dealing with gauge theory can be found here, but I doubt we will need it in this note.

Quantum mechanics is defined over the spatial coordinates $\vec{x}$. The position eigenstates $\left\lvert{\vec{x}}\right\rangle$ form a complete basis of the Hilbert space. However, $\left\lvert{\vec{x}}\right\rangle$ is represented by a Dirac $\delta$-function, which does not belong to the Hilbert space of $L^{2}(\mathbb{R}^{d})$, where $d$ is the dimension of the space, as usually. It is a challenge to mathematical rigor of quantum mechanics.

Recall that the Hilbert space $L^{2}(\mathbb{R}^{d})$ consists of all square-integrable functions defined on $\mathbb{R}^{d}$, with an inner product $\left\langle f,g \right\rangle=\int dx \, f^{\ast}g$. This inner product also defines a norm, and with norm we can talk about Cauchy completeness. The space $L^{2}$ is indeed Cauchy complete, since we do not require functions in it to be smooth. The Cauchy completeness makes it a Hilbert space, not a pre-Hilbert space.

To deal with mathematical objects such as the Dirac $\delta$-function, quantum mechanics often uses the concept of rigged Hilbert space, also known as a Gelfand triplet. A rigged Hilbert space involves three components:

- Schwartz space $\mathcal{S}$, the space of rapidly decreasing smooth functions. It is a dense subspace of the Hilbert space that we talk about in the next paragraph. By working with $\mathcal{S}$, we can rigorously define unbounded operators and their domains. States here are smooth and decays faster than any polynomial, making them suitable for rigorous operator definitions.

- Hilbert space $L^{2}$. The Schwartz space $\mathcal{S}$ is a dense subset of $L^{2}$. Here is where all the quantum states reside. These states are normalizable and have finite norm.

- Dual space $\mathcal{S}^{\ast}$. It includes functionals, also called generalized states. The Dirac delta function represents the position eigenstate, while plane waves represent momentum eigenstates, we can’t fit them into the Hilbert space $L^{2}$, here is where these pathological states reside.

The relationship can be written as

\[\mathcal{S} \subset L^{2} \subset \mathcal{S}^{\ast }.\]Actually, I don’t think it makes a lot of sense to regard $\left\lvert{\vec{x}}\right\rangle$ as a physical state, since in real life, due to the uncertainty principal, a particle will never be localized at a specific point. Instead, the position always smears about a certain region, so is its momentum. The role of $\left\lvert{\vec{x}}\right\rangle$ is more of giving us the value of the wave function at position $\vec{x}$, in other words, what naturally appears is the dual version $\left\langle{\vec{x}}\right\rvert$ of $\left\lvert{\vec{x}}\right\rangle$. $\left\langle{\vec{x}}\right\rvert$ can be regarded as map that takes a state in the Hilbert space of quantum states, and spits out a complex number:

\[\begin{align*} \left\langle{\vec{x}}\right\rvert : \quad \mathcal{H} &\to \mathbb{C} \\ \left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle &\mapsto \psi(\vec{x}), \end{align*}\]where $\mathcal{H}$ is not the Hamiltonian but the Hilbert space of quantum states.

For a state $\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle$ to be a physical state, it should be sensible to talk about

\[\left\langle{\psi}\right\rvert \mathcal{O} \left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle ,\quad \mathcal{O}\text{ is an observable.}\]$\left\lvert{\vec{x}}\right\rangle$ fails this requirement since $\left\langle{\vec{x}}\right\rvert \hat{x} \left\lvert{\vec{x}}\right\rangle=\infty$, this is another reason to say that $\left\lvert{\vec{x}}\right\rangle$ is not a physical state.

We distinguish two concepts, states and wave function. In quantum mechanics, they are sometimes used interchangeably, but they have distinct meanings. A quantum state contains all the information about the system. It can be described in different representations, depending on what information we want to know. For example, if we want to know information about the position, we go to the physical space representation expanded by $\left\lvert{\vec{x}}\right\rangle$. Quantum states can be represented as vectors in a Hilbert space, and there exists pure and mixed states. On the other hand, the wave function is a specific representation of a quantum state in the position (or sometimes momentum) basis. It is a complex-valued function that gives the probability amplitude of finding a particle in a particular position in space. The wave function of a state $\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle$ is denoted by $\psi(x)$, where $x$ is the position.

In the passive perspective, a state before and after spatial translation is the same state, they just have different wave functions, because in order to get the wave function we need two things: bases and a state, even though the state is unchanged but the bases are changed now, thus the final expression is also changed.

Consider a scalar field theory. All the possible configuration of $\phi$ form the configuration space $\mathcal{C}$, each point represents a specific field function $(\mathcal{M}\times\mathbb{R})\to \mathbb{C}$, where $\mathcal{M}$ is the space manifold and $\mathbb{R}$ the time dimension. The wave functional $\Psi[f(x)]$ describes the quantum state at a given time, we have

\[\Psi: \mathcal{C} \to \mathbb{C}, \quad f (\vec{x}) \mapsto \Psi[f].\]Similar to quantum mechanics where $\left\lvert{\vec{x}}\right\rangle$ is the eigen state of $\hat{x}$ and $\hat{x}\left\lvert{\vec{x}}\right\rangle=\vec{x}$, in QFT the eigen state of field operator $\hat{\phi}$ satisfy

\[\hat{\phi}(\vec{x})\left\lvert{\phi}\right\rangle = \phi(\vec{x})\left\lvert{\phi}\right\rangle ,\]Any wave functional can be given as a superposition of such eigen states. Let $\left\lvert{\Psi}\right\rangle$ be a well-behaved wave functions, it can be formally written as

\[\left\lvert{\Psi}\right\rangle = \int D\phi(\vec{x}) \, \Psi[\phi(\vec{x})] \left\lvert{\phi(\vec{x})}\right\rangle ,\]We will simply write $\phi$ and omit the spatial coordinate.

Given the quantum state $\left\lvert{\Psi}\right\rangle$, the amplitude of a certain configuration $\phi$ is

\[\Psi [\phi(\bullet)] = \left\langle \phi \middle\vert \Psi \right\rangle \in \mathbb{C}.\]As a consistency check, let’s see if we can reproduce the result $\left\langle{\Psi}\right\rvert\hat{\phi}(\vec{x}) \left\lvert{\Psi}\right\rangle=\psi(\vec{x})$ for some classical field $\psi(\vec{x})$. We have

\[\begin{align*} \left\langle{\Psi}\right\rvert \hat{\phi}(\vec{x})\left\lvert{\Psi}\right\rangle &= \int D\varphi \, \Psi ^\ast [\varphi]\left\langle{\varphi}\right\rvert\, \hat{\phi}(\vec{x})\,\int D\varphi' \, \Psi[\varphi']\left\lvert{\varphi'}\right\rangle \\ &= \int D\varphi \, \Psi^\ast [\varphi] D\varphi' \, \Psi[\varphi']\left\langle{\varphi}\right\rvert\, \varphi'(\vec{x})\left\lvert{\varphi'}\right\rangle \\ &= \int D\varphi \, \Psi^\ast [\varphi] D\varphi' \, \Psi[\varphi'] \varphi'(\vec{x}) \delta(\varphi-\varphi') \\ &= \int D\varphi \, \Psi^\ast [\varphi]\, \Psi[\varphi] \varphi(\vec{x}) \\ &= \int D\varphi \, \left\lvert \Psi[\varphi] \right\rvert^{2} \varphi(\vec{x}), \end{align*}\]and recall that $\left\lvert \Psi[\varphi] \right\rvert^{2}$ is the probability of finding $\varphi$ in $\Psi$, thus indeed we have

\[\int D\varphi \, \left\lvert \Psi[\varphi] \right\rvert^{2} \varphi(\vec{x}) = \left\langle \hat{\phi}(\vec{x}) \right\rangle =: \psi(\vec{x}).\]Time evolution is generated by the Hamiltonian, yielding a functional Schrodinger equation:

\[i\hbar \left\lvert{\Psi[\phi]}\right\rangle = \hat{H}\left\lvert{\Psi[\phi]}\right\rangle ,\]For the ground state (or vacuum state) of the free scalar field, the wave functional $\Psi_0[\phi]$ has a Gaussian form, it is basically an infinite lattice of harmonic oscillators. It can be written as:

\[\Psi_0[\phi] = N \exp \left( -\frac{1}{2} \int d^3x \, d^3y \, \phi(x) K(x,y) \phi(y) \right)\]| where $N$ is a normalization constant, and $K(x,y)$ is a kernel that depends on the mass $m$ of the scalar field and the spatial separation $ | x - y | $. |

For a free scalar field, $K(x,y)$ can be written in terms of the Fourier transform:

\[K(x,y) = \int \frac{d^3k}{(2\pi)^3} \, \omega_k \, e^{i k \cdot (x - y)}\]with $\omega_k = \sqrt{k^2 + m^2}$.

The wave functional $\Psi_0[\phi]$ provides the probability amplitude for the field configuration $\phi(x)$. The exponential form indicates that the ground state is a Gaussian distribution centered around $\phi(x) = 0$, reflecting the fact that the vacuum state has no preferred field configuration (zero field on average).

For more information refer to this post.

Kink modes $\mathfrak{g}(\vec{x})$ in 2D

Since we assumed the domain wall to be lying flat in the $y$-plane, the normal modes in 2-d space can be factorized into $x$ and $y$ components,

\[{\mathfrak g} _ {k_ {x}k_ {y}} (x,y) = {\mathfrak g}_ {k_ {x}}(x) \times e^{ -i y k_ {y}}.\]The normal modes are the solution of the equation of motion in the kink background, or Poschl-Teller potential. These modes include a continuum

\[{\mathfrak g} _ {k}(x) = \frac{e^{-ikx}}{\omega_ {k} \sqrt{m^2+4k^2}}\left[2k^2-m^2+(3/2)m^2\text{sech}^2(m x/2)-3im k\tanh(m x/2)\right]\]with eigenvalue $\omega_ {k} = \sqrt{ k^{2}+m^{2} }$, a zero mode

\[{\mathfrak g}_ {B} = -\sqrt{ \frac{3m}{8} } \text{sech}^{2}\left( \frac{mx}{2} \right)\]with eigenvalue $0$, and a shape mode

\[{\mathfrak g} _ {S} = \frac{\sqrt{ 3m }}{2} \tanh \frac{mx}{2} \text{sech} \frac{mx}{2},\quad \omega_ {S} = \frac{\sqrt{ 3 }}{2}m\]with eigenvalue less then the rest mass of excited particle.

Momentum in the $y$-direction also contributes to the total energy, putting them together with the zero modes, shape modes and continuum in the $x$ direction we have

\[\boxed { \omega_ {k_ {B}k_ {y}} = \left\lvert k_ {y} \right\rvert ,\quad \omega_ {k_ {S}k_ {y}} = \sqrt{ \frac{3m^{2}}{4}+k_ {y}^{2} },\quad \omega_ {k_ {x} k_ {y}} = \sqrt{ m^{2}+k_ {x}^{2}+k_ {y}^{2} }. }\]Note that

- there is a zero mode corresponding to $k_ {B},k_ {y}=0$,

- the mass gap disappears, due to the mass-gap-less of $y$-momentum.

The formalism we developed in generic dimension $d$ surely also applies to $d=2$. Let $\vec{p}=(p_ {x},p_ {y})$ and $\vec{k}=(k_ {x},k_ {y})$. The Fourier transform is

\[\tilde{\mathfrak{g} }_ {k_ {x},k_ {y}} (\vec{p})= \int d^{2}x \, \mathfrak{g} _ {k}(\vec{x}) e^{ -i\vec{k}\cdot \vec{x} } = (2\pi)\delta(k_ {y}+p_ {y}) \times \tilde{\mathfrak{g}} _ k (p_ {x}).\]Again we see the factorization in $x$ and $y$, the $\delta$-function in $y$ direction is due to the plane wave expansion.

Note that the infinite volume of a flat $\mathbb{R}$ can be written as Dirac-$\delta$ function $\delta(0)$. To see it, recall the Fourier transform of a function is written as

\[\widetilde{f}(\vec{k}) = \int d^{d}x \, e^{ -i\vec{k}\cdot \vec{x} } f(\vec{x})\]which means if we set $f(\vec{x})=1$ then

\[\tilde{f}(\vec{k}) = \int d^{d}x \, e^{ -i \vec{k}\cdot\vec{x} } = (2\pi)^{d} \delta^{d}(k),\]If we further set $k=0$ then the integral becomes

\[\int d^{d}x \, 1\, = \text{Vol}^{d} = (2\pi)^{d}\delta^{d}(0).\]In the case of 1-dimension, say coordinated by $y$, the total length would be $2\pi \delta(0)$.

Define the Fourier transformation $\tilde{f}$ of function $f(x)$ to be

\[\tilde{f}(\vec{p}) := \int d^{d}x \, f(\vec{x})e^{ -i\vec{p}\cdot \vec{x} }.\]The Fourier transformation of normal modes reads

\[\tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k}(p) = \int d^{d} x \, {\mathfrak g}_ {k}( \vec{x} ) e^{-i\vec{p} \cdot \vec{x} }\]which satisfies relation

\[\tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k}^{\ast}(\vec{p}) = \tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {-k}(-\vec{p}) .\]Sometime this relation can help to make the numerical calculation easier.

The normalization relations for ${\mathfrak g}$ reads

\[\begin{align*} \int d^{d}x \, {\mathfrak g}^{\ast }_ {k}(\vec{x}){\mathfrak g}_ {k'}(\vec{x}) &=(2\pi)^{d}\delta ^{d}(\vec{k}-\vec{k}'), \\ \int \frac{d^{d}p}{(2\pi)^{d} } \tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k}(\vec{p}) \tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k'}(\vec{p}) &= (2\pi)^{d}\delta ^{d}(\vec{k}+\vec{k}'), \\ \int \frac{d^{d}p}{(2\pi)^{d} } \tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }_ {k}(\vec{p}) \tilde{ {\mathfrak g} }^{\ast }_ {k'}(\vec{p}) &= (2\pi)^{d}\delta ^{d}(\vec{k}-\vec{k}') , \end{align*}\]and the completeness condition (in both spacetime and momentum space)

\[\begin{align*} \int \frac{d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{2}} \, {\mathfrak g}_ {k}(\vec{x}) {\mathfrak g}^{\ast }_ {k}(\vec{y}) &=\delta ^{d}(\vec{x}-\vec{y}), \\ \sum\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\int \; \frac{d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{d}} \, \tilde{ {\frak g} }_ {k}(\vec{p}_ {1}) \tilde{ {\frak g} }^{\ast} _ {k}(\vec{p}_ {2}) &= (2\pi)^{d} \delta^{d}(\vec{p}_ {1} - \vec{p}_ {2}). \end{align*}\]Note that in our convention of Fourier transformation, instead of $+i\vec{p}\cdot \vec{x}$ we have minus sign. This is only the spatial part of the Fourier transformation (recall that our spacetime is $d+1$ dimensional).

-

J. Polchinski, String Theory. Vol. 1: An Introduction to the Bosonic String. Cambridge Univ. Pr., UK, 1998. ↩

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: