Perturbative SSB and Effective Action

- 1. Spontaneous symmetry breaking

- 2. Degenerate Vacua, Good and Bad

- 3. Effective Action

- 4. The Physical Meaning of the Effective Potential

This note is based on Chapter 44 of Lectures of Sidney Coleman on Quantum Field Theory.

1. Spontaneous symmetry breaking

This section can be neglected.

The word spontaneous used to baffle me. It doesn’t seem so “spontaneous” in the context of quantum field theory, such as $\phi^{4}$ model. At least not spontaneous enough in comparison with that in the Ising model. In Ising model, starting from high temperature, above Curie temperature to be specific, the ferromagnetic system is in a rotational symmetric phase, all the little spins point to random directions. As the temperature drops, at the Curie temperature the system undergoes a second order phase transition, the system picks a direction and all of a sudden, most of the spins are aligned in that directions,as a result the rotational symmetry is broken, without any external manipulation, hence the word spontaneous. To be more specific, take 2D (spatial) Ising model for example, which is famously solved by Lars Onsager. We don’t choose 1D Ising model because in 1D, spontaneous symmetry breaking doesn’t occur due to the lack of a phase transition at finite temperatures, there is a critical dimension under which the free energy is dominated by entropy, so the order phase is not preferred, according to the so-called energy-entropy argument.

For a 2D lattice with spins (which can take values +1 or -1, representing up or down magnetic moments) located on each site, the Hamiltonian is given by:

\[H = -J \sum_ {\langle i, j \rangle} s_ i s_ j - h \sum_ i s_ i\]where $J$ is the exchange interaction energy between neighboring spins. It determines the strength of the interaction and can be positive (favoring alignment) or negative (favoring anti-alignment). The sum $\sum_ {\langle i, j \rangle}$ runs over all nearest-neighbor pairs of lattice sites, ensuring that each pair is counted once. $s_ i$ and $s_ j$ are the spin values at sites $i$ and $j$, respectively. $h$ is the external magnetic field, but for the spontaneous phase transition discussion, we consider $h = 0$.

The free energy (Helmholtz free energy, to be specific) $F$ of the system combines the internal energy and the entropy. Classically speaking, the free energy describes the work that can be extracted from a system at a constant temperature, but here the physical meaning is that the equilibrium state is such that minimizes the free energy. The free energy in the context of the Ising model can be expressed as:

\[F = -k_ B T \ln(Z)\]where $k_ B$ is the Boltzmann constant, $T$ is the temperature, and $Z$ is the partition function of the system, given by the sum over all possible configurations:

\[Z = \sum_ {\left\lbrace s \right\rbrace } e^{-\beta H(\left\lbrace s \right\rbrace )}\]where $\beta = \frac{1}{k_ B T}$ and $H(\left\lbrace s \right\rbrace )$ is the Hamiltonian for a particular configuration $\left\lbrace s \right\rbrace$ of spins.

The true ground state must minimize the free energy, the free energy is energy minus temperature times entropy, hence the competition between energy and entropy underlies the phase transition:

- At low temperatures, the system tends to minimize its energy, leading to an ordered phase where spins align (ferromagnetism).

- At high temperatures, the entropy dominates, favoring a disordered state where spins are randomly oriented.

The balance between these two tendencies determines the critical temperature $T_ c$ at which the phase transition occurs.

The critical dimension $d_ c$ of a system is the minimum dimension in which a phase transition can occur at a nonzero temperature. For the Ising model, it is known that $d_ c = 1$ for a lower critical dimension, meaning that there is no phase transition at any nonzero temperature in 1D. In 2D, however, the model does exhibit a phase transition, as shown by Onsager’s solution.

Onsager’s exact solution for the 2D Ising model on a square lattice without an external field showed that the critical temperature $T_ c$ is given by:

\[\sinh\left(\frac{2J}{k_ B T_ c}\right) = 1\]This solution demonstrated that a spontaneous magnetization (order) emerges below $T_ c$ and disappears above $T_ c$, marking a second-order phase transition characterized by a continuous change in the order parameter (magnetization).

The calculation of the critical properties, such as the critical exponents that describe how physical quantities diverge near $T_ c$, is more intricate and relies on sophisticated mathematical techniques, including renormalization group analyses, which go beyond the scope of this note.

In the contest of quantum field theory, spontaneous symmetry breaking occurs when the most stable state (or states) of a system, namely its ground state or vacuum state, does not share the symmetry of the system’s Lagrangian (or Hamiltonian). This can happen even though the governing equations or Lagrangian of the system remain symmetric. The system “chooses” a state that breaks some of the symmetry of the Lagrangian.

The Higgs mechanism is a well-known example of spontaneous symmetry breaking in QFT. The potential of the Higgs field is symmetric, resembling a “Mexican hat” or “sombrero,” but the lowest energy state (the ground state) is not at the symmetric center (where the field value is zero) but rather at some nonzero value along the “brim” of the hat. This asymmetric ground state breaks the symmetry of the potential.

The “spontaneous” aspect is that there’s no external force or parameter explicitly breaking the symmetry; it’s the intrinsic dynamics of the field settling into a minimum energy state that breaks the symmetry. Spontaneous in the context of QFT is not in the dynamical sense, as it is in Ising model.

2. Degenerate Vacua, Good and Bad

In a simple quantum system, you might expect a unique ground state. However, in systems where spontaneous symmetry breaking occurs, there can be multiple degenerate ground states, all having the same energy but different physical configurations.

All the vacua together form the manifold of vacuum of the Lagrangian, where the basis are just different vacua states, continuous or not. The thing is, there is more than one set of basis for the vacuum states. Let $\left\lvert{0,\alpha}\right\rangle$ be degenerate vacuum states label by some $\alpha$, then any linear combination, properly normalized, is another vacuum state, call it $\left\lvert{0,\beta}\right\rangle$, then we can use the Gram-Schmidt procedure to construct another set of orthonormal basis. Among the infinite sets of basis, there do exists good sets and bad ones. But before defining what is a good vacuum, we must first define what is a quasi-local operator.

Recall that operators correspond to observable quantities or actions that can be performed on the field, and “quasilocal” operators are those whose effects are confined to a limited region of space. Take the scalar field theory for example, let $\phi(x)$ be field operator, they are local since it is defined on a point. A quasilocal operator $A$ is something can be constructed from $\phi$ via

\[A = \int d^{d}x \, f(x_ {1},\cdots,x_ {n}) \phi(x_ {1})\cdots\phi(x_ {n})\]where $f(x_ {1},\cdots,x_ {n})$ is a function with finite support (support is the closure of the points where $f$ is nonzero).

Now coming back to vacua. There is a basis where all the vacua are globally independent, where one vacua can not be transformed into another using some local (or quasi-local, as Coleman called it) operator. Such a basis is called good vacuum states. For a set of good vacua, different vacuum states are not just distinct but are fundamentally separate in the sense that you cannot use a simple, localized operation to move from one to another. By construction, the vev of any quasilocal operators between two distinct good vacua is zero,

Theroem 1 There exists a basis for the vacuum states $\left\lvert{0,\alpha}\right\rangle$, so called good vacuum states, such that for any quasilocal operator $A$, we have

\[\left\langle{0,\alpha}\right\rvert A\left\lvert{0,\alpha'}\right\rangle =0.\]We’ll neglect the proof of the theorem here, just mention that it involves translational invariance of vacuum states, causality, and some cluster decomposition-ish argument.

The significance of the theorem is this: it doesn’t matter if you say there’s one vacuum or many; there are always good vacua. It shows that, even if we don’t know anything about spontaneous symmetry breaking, and we’ve chosen a bad set of vacua, by a systematic constructive procedure we can always find a good choice of bases for the vacuum subspace, such that no local operator can connect one vacuum to another.

In the following we will need to make use of quantum effective action $\Gamma[\varphi]$, for details on this topic see my other note here.

As explained by Coleman,

…(using perturbation theory), but with the effective action $\Gamma[\overline{\phi}]$ substituted for the classical action $S[\phi]$. Instead of trying to find minima by finding the stationary points of the classical action, I find ground states by looking at the stationary points of the effective action; instead of finding effective coupling constants and masses by expanding about the minima of the classical action, I find 1PI Green’s functions by expanding about the minima of the effective action. It’s exactly the same game in the quantum and classical theories.

Sometimes Coleman talks about classical vev of $\phi$ and quantum vev of $\phi$. By his definition, the classical vev of $\phi$, i.e. $\left\langle \phi \right\rangle$ classical, usually denoted as just $\left\langle \phi \right\rangle$, is the vev of $\phi$ without loop corrections, the quantum one, usually denoted as $\overline{\phi}$, is that with loop corrections. In any cases, $\left\langle \phi \right\rangle$ is supposedly a constant in spacetime. This means that both classical and quantum vacuum preserves the translational symmetry.

In solitonic quantum field theory we constantly deal with ground states that are not translations symmetric. Regarding the possibility of SSB of spontaneous translational symmetry breaking, Coleman comment

There’s no reason why translation invariance should not be spontaneously broken in a theory that describes the real world. It occurs in statistical mechanics, for example, where the phenomenon is called

crystallization. There, instead of changing the square of the mass to cause the manifest symmetry to break spontaneously, one changes the temperature. Let’s take a typical material such as iron, and imagine an iron universe, spatially infinite. If the temperature is above a certain point, the ground state (in the sense of statistical mechanics) is spatially homogeneous; it’s iron vapor. We lower the temperature below the freezing point of iron, and the ground state becomes an infinite iron crystal, which does not have spatial homogeneity. If we now consider the rotation of a crystal somewhere in the frozen iron, how it rotates depends on its position relative to a central lattice point. That’s an example of spontaneous symmetry breakdown of translational invariance.

Note that spontaneous symmetry breaking does not affect the renormalization, SSB is essentially a shift of field, has nothing to do with regularization and renormalization. A SSB model has exactly the same counter terms as the original one. Thus we could renormalize first and shift the field later. This is useful in $\phi^{4}$ model with spontaneous symmetry breaking, since the original theory has no $\phi^{3}$ terms but the symmetry broken theory has, so naturally one could ask, do we need a counter term for $\phi^{3}$ interaction, like Mark Srednicki did in his textbook? The answer is no since such a counter term is not needed in the original theory. Then what about the divergence introduced by $\phi^{3}$ theory? Well, if we had done everything correctly, it should be taken care of by itself, by some destined cancellation. Like Coleman said,

After we do the shift, of course, a $\phi^{3}$ interaction will appear in the effective action, but we still don’t need a $\phi^{3}$ counterterm, because we’ve already gotten rid of all infinities in computing $\Gamma$ before we’ve made the shift. The shift is a purely algebraic operation without a single integration over internal momenta, and therefore cannot possibly introduce new ultraviolet infinities.

Say we are doing renormalization in the original theory. What are the renormalization conditions? We have MS, $\overline{\text{MS}}$, Pauli-Villas, mass-shell, lattice, Momentum Subtraction, etc. It is not a good idea to adopt the mass shell renormalization since in the original theory $m^{2}<0$. Then we could choose a tentative renormalization condition, then adjust it in the kink sector so that the renormalized parameters are physical. The vev of field $\overline{\phi}$ will depend on the renormalization condition, but different condition will describe the same physics.

Recall that the effective action $\Gamma[\overline{\phi}]$ is made of 1PI diagrams, where $\overline{\phi}(x)$ itself serves as the external legs, just like the source term $J(x)$ with classical action $S$. We have assumed the $\overline{\phi}$ is a const in spacetime, which translates to zero momentum after we Fourier transform it to the momentum space. So we only need to consider the case where the external legs has zero momenta. Next let’s dive into calculation.

3. Effective Action

Let $V(\overline{\phi})$ be the effective action of $\overline{\phi}$, which if you recall is the quantum vev of $\phi$. For the details of effective action see my other note mentioned at the beginning of this note, here we only present the definition,

where $\text{Vol}^{d}$ is the total space of the $d$-dimensional spacetime manifold.

The connection between $\Gamma[\overline{\phi}]$ and $S[\overline{\phi}]$ is that, at tree level, that is if you forget about quantum corrections, $\Gamma$ is equal go $S$. When the quantum corrections are included, since $\Gamma$ is exact (incorporates all the quantum effects in path integral) at tree level, we have

\[Z[J] = \lim_ { \hbar \to 0 } \int \mathcal{D}\phi \, \exp \left\lbrace \frac{i}{\hbar}\left( \Gamma[\phi]+\int J\phi \right) \right\rbrace = \exp \left\lbrace i\Gamma[\overline{\phi}]+\int dJ\overline{\phi} \, \right\rbrace ,\]it is understood that the last equality is up to multiplicative constants. Also note that in the last expression it is not just any $\phi$, but $\overline{\phi}$ that satisfies certain functional equation, which is exactly the $\overline{\phi}$ we have been using.

However we also have

\[Z[J] = \int \mathcal{D}\phi \, \exp \left\lbrace \frac{i}{\hbar}\left( S[\phi] +\int J\phi \right) \right\rbrace = \exp \left\lbrace iS[\left\langle \phi \right\rangle ] + \text{loops} \right\rbrace\]where loops are a result of the fluctuations about the classical field configuration $\left\langle \phi \right\rangle$. Thus we have

\[\Gamma[\overline{\phi}] = S[\left\langle \phi \right\rangle] + \text{loops}= S[\overline{\phi}] + \text{loops},\]since a swap between $\overline{\phi}$ and $\left\langle \phi \right\rangle$ introduces loop corrections only. But so far let’s stick with $S[\left\langle \phi \right\rangle]$ instead of $S[\overline{\phi}]$, since $\left\langle \phi \right\rangle$ is the quantum vev thus unknown, while $\left\langle \phi \right\rangle$ is the classical vev thus easily known, one just need to solve for the equation of motion.

Write the action in terms of the Lagrangian we have

\[\Gamma[\overline{\phi}] = \int d^{d}x \, \mathcal{L}(\left\langle \phi \right\rangle ) + \text{loops}.\]We have

\[\mathcal{L} = \frac{1}{2} (\partial \phi)^{2} - U(\phi) + \mathcal{L}_ {\text{ct}},\]where $U$ is the classical potential and $\mathcal{L}_ {\text{ct}}$ are the counter terms. Then, since $\overline{\phi}$ is constant we have

\[V(\overline{\phi}) = U(\left\langle \phi \right\rangle ) + \text{loops},\]where loop contribution is of form $\hbar(\text{1-loops})+h^{2}(\text{2-loops})+\cdots$. Note that $V(\overline{\phi})$ is not a functional but rather a function of $\overline{\phi}$, it is the negative of the constant density of $\Gamma[\overline{\phi}]$. Since $\Gamma$ generates all the 1PI diagrams, $V(\overline{\phi})$ represents the collection of all the 1PI diagrams with all the external momenta equal to zero and with the $(2\pi)^{d}\delta^{d}(0)$ from overall energy-momentum conservation divided out. That’s just the Fourier space equivalent of the integral $\int d^dx$.

As Coleman explained in his lecture notes,

The rule for computing $V[\overline{\phi}]$ is very simple. You don’t have to worry about any external momentum. You just have external lines each carrying zero momentum. Sum up all those graphs to one loop or two loops or however many loops you’re going to do.

3.1. Calculating the 1-Loop Effective Potential

With a general renormalizable potential, we start with the Lagrangian that reads

\[\mathcal{L} = \frac{1}{2} (\partial \phi)^{2} -U(\phi)+\mathcal{L}_ {\text{ct}}.\]If there is a mass term it goes to $U$. As a result, the propagator is

\[\frac{i}{k^{2}+i\epsilon}.\]Recall that calculating $\Gamma[\overline{\phi}]$ means calculating the 1PI diagrams with external legs amputated and replaced by a factor of $\overline{\phi}$. Why are they amputated? We know that when calculating the S-matrix the external legs are also truncated due to the LSZ theorem, but here there is no LSZ theorem so why does it happen? The reason is mostly that 1PI diagrams are used to represent the interaction vertices or the “effective vertices” in the theory, rather than full scattering processes. In the context of effective theory you usually don’t hear things like asymptotic states, scattering matrix, things that you must discuss when talking about S-matrix. The 1PI diagrams contribute to the n-point functions, which are essentially the building blocks of the full scattering amplitudes. These vertex functions describe how particles interact at a point, disregarding the propagation of particles to and from this point. In the renormalization process, 1PI diagrams are essential because they contain the divergences that need to be renormalized. The external propagators do not need to be renormalized in the same way, so they are not included in the 1PI diagrams. The renormalization of the theory focuses on the interactions themselves, which are represented by the 1PI diagrams without the external propagators. For details please refer to note here, at the paragraph before Eq. (15).

From the functional Taylor expansion of $i\Gamma[\varphi]$ in momentum space,

\[\begin{align*} i\Gamma[\varphi] &= \sum_ {n} \frac{1}{n!} \int \frac{dk_ {1}^{d}}{(2\pi)^{d}} \cdots \frac{dk_ {n}^{d}}{(2\pi)^{d}}\, \tilde{\varphi}(-k_ {1})\cdots \tilde{\varphi}(-k_ {n} )\tilde{\Gamma}^{(n)}(k_ {1},\cdots, k_ {n} )\\ &\;\;\;\; \times (2\pi)^{d}\delta^{d}(k_ {1}+\cdots +k_ {n} ), \end{align*}\]we can expand $\tilde{\Gamma}^{(n)}(k_ {1},\cdots,k_ {n})$ in terms of $k$’s, while keeping the $\tilde{\varphi}$’s untouched, the reason why we don’t expand $\tilde{\varphi}$ is purely technical, because an expansion in $\Gamma^{(n)}$ suffices. If we do that, at the leading order where $k=0$ for all $k$, then we get

\[i\Gamma[\varphi] = \sum_ {n} \frac{1}{n!} \int d^{d}x \, \tilde{\Gamma}^{(n)}(0,\cdots ,0) \varphi^{n}(x) + \mathcal{O}(k).\]Note that $\varphi(x)$ are functions of $x$, not its Fourier transformed $\tilde{\varphi}$, which is a result from not expanding $\tilde{\varphi}(k)$ in $k$.

By the definition of effective action

\[\Gamma[\varphi] = -\int d^{d}x \, V_ {\text{eff}}(\overline{\phi}) + \mathcal{O}(\text{derivatives}),\]we have

\[\boxed { V_ {\text{eff}}(\overline{\phi}) = i\sum_ {n} \frac{1}{n!} \int d^{d}x \, \tilde{\Gamma}^{(n)}(0,\cdots ,0) \overline{\phi}^{n}(x) . }\]note we have replaced $\varphi$, a generic classical field to $\overline{\phi}$, the vacuum solution we want to expand about. It doesn’t change the logic or the derivation, just replacing the general case with a special case.

In $\phi^{4}$ model, at tree level, we have

\[\Gamma^{(2)} (0,0) = -i \mu^{2},\quad \Gamma^{(4)}(0,0,0,0) = -i \lambda,\]where $\mu^{2}$ is the mass of the particle and $\lambda$ the coupling. Of course it depends on how you write the Lagrangian, could differ a factor of $3!$ or something like that.

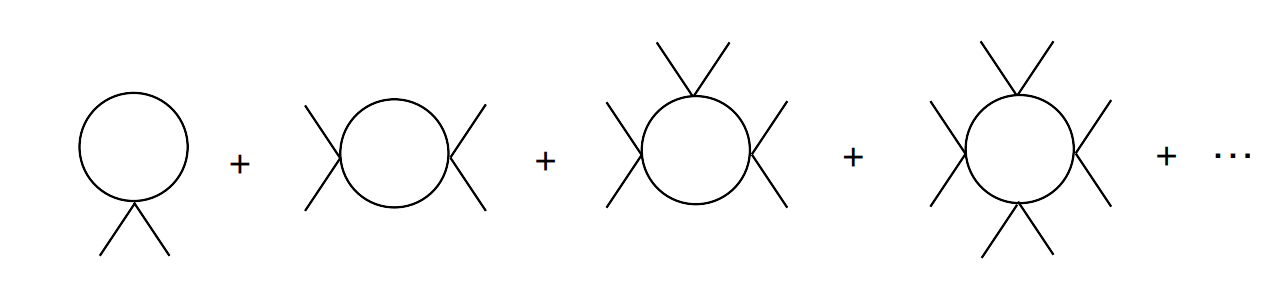

To include the 1-loop corrections, we need to consider 1PI diagrams shown in Fig. (1).

The $2n$-point amplitude shown in Fig. 1 read

\[\Gamma^{(2n)} (0,\cdots,0) = \frac{(2n)!}{2^{n}(2n)} \int \frac{d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{d}} \, \left( \frac{i}{k^{2}+i\epsilon}(-i\lambda) \right)^{n}.\]Some explanation is in order: for $2n$ external legs, there will be $n$ propagators with the same momentum $k$ (since the external legs all carry zero momentum by construction), and there are $n$ vertices. $2^{n}$ is the symmetry factor for each vertex (for the two external legs), $2n$ in the denominator is the symmetry factor for the entire loop, for $n$ rotations and $n$ reflections. There are $(2n)!$ different ways to assign $x_ {1},\cdots,x_ {2n}$ (in coordinate representation of course) to the $2n$ “bulbs”, hence the factor $(2n)!$. If you are confused about this, just think of what we did with $iW[J]$ when using it to generate connected diagrams, where for a diagram with $n$ external legs, there are $n!$ ways to assign it. For more details refer to Chapter 13 in lectures of Sidney Coleman on quantum field theory, here I just quote a short passage from Coleman that is relevant to our discussion:

If we imagine restricting ourselves to the case where the first $\rho$ gives up momentum $k_ {1}$, the second gives a momentum $k_ {2}$, etc., then all of our lines are well-defined, and we have no factor of $1/n!$. On the other hand, when we integrate over all $k$’s in this expression, we overcount each those terms $n!$ times, corresponding to the $n!$ permutations of a given set of $k$’s, and therefore we need a $1/n!$ to cancel it out. I know combinatoric arguments are often not clear the first time you hear them, but after a little thought, they become clear.

Coleman also emphasized that here we are not normal ordering anything. Normal ordering tend to cause some problems, including 1) it is not compatible with gauge transform, 2) it is not compatible with field shift and 3) it sometimes messes up the symmetry.

Also note that even we are talking about 1-loop only, there is arbitrary high power of coupling $\lambda$. This is different from what I am used to in calculating loops, where higher power of coupling usually implies higher number of loops. This is not a problem though.

We can go beyond $\phi^{4}$ model to a general polynomial potential $U(\phi)$ (recall that $V$ is preserved for quantum potential), then each vertex on the circle would contribute $-iU’’(\phi)$, where prime means the derivative w.r.t. $\phi$ field. Then for loops with $n$ vertices as shown in Fig.1 we have

\[\text{circle with }n \text{ vertices} = \frac{1}{(2n)} \int \frac{d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{d}} \, \left( \frac{U''(\overline{\phi})}{k^{2}+i\epsilon} \right)^{n}.\]To obtain $\Gamma[\overline{\phi}]$ we just need to sum them up together, we have

\[\text{loop correction} = \sum_ {n} \frac{i}{2n} \int \frac{d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{d}} \, \left( \frac{U''(\overline{\phi})}{k^{2}+i\epsilon} \right)^{n}\]which is the Taylor expansion of $-\ln(1-\bullet)$, if we forget about convergence for now,

\[\sum_ {n} \frac{i}{2n} \int \frac{d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{d}} \, \left( \frac{U''(\overline{\phi})}{k^{2}+i\epsilon} \right)^{n} = - \frac{i}{2} \int \frac{d^{d}k}{(2\pi)^{d}} \, \ln\left( 1-\frac{U''(\overline{\phi})}{k^{2}+i\epsilon} \right),\]to proceed we need to go to Euclidean space by performing Wick rotation,

\[\text{loops} = \frac{1}{2} \int \frac{d^{d}k_ {E}}{(2\pi)^{d}} \, \ln\left( 1-\frac{U''(\overline{\phi})}{-k_ {E}^{2}+i\epsilon} \right),\]where $d^{d}k_ {E} = dk_ {E} k^{d-1}_ {E } \Omega_ {d-1}$ for spherically symmetric functions, $\Omega_ {d-1}$ is the area of unit $(d-1)$-sphere. We are only interested in what depends on $\overline{\phi}$, not the constant part (w.r.t $\overline{\phi}$), infinite or not.

Cut off $k_ {E}$ at $\Lambda$ and discard some additive infinite stuff which we can absorb into the normalization, we get

\[\begin{align*} \text{loops} &= \frac{1}{2} \int^{\Lambda}_ {0} \frac{d^{d}k_ {E}}{(2\pi)^{d}} \, \ln\left( 1 +\frac{U''(\overline{\phi})}{k_ {E}^{2}-i\epsilon} \right) \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \int_ {0}^{\Lambda} \frac{d^{d}k_ {E}}{(2\pi)^{d}} \, \ln\left( \frac{k_ {E}^{2}+U''(\overline{\phi})-i\epsilon}{k_ {E}^{2}-i\epsilon} \right) \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \int_ {0}^{\Lambda} \frac{d^{d}k_ {E}}{(2\pi)^{d}} \, \ln(k_ {E}^{2}+U''(\overline{\phi})-i\epsilon) + \text{Const} \\ &= \frac{1}{2(2\pi)^{d}} \int_ {0}^{\Lambda} d^{d}k_ {E} \, k_ {E}^{d-1} \Omega_ {d-1} \ln(k_ {E}^{2}+U''(\overline{\phi})-i\epsilon) \end{align*}\]where in the last step we have carelessly thrown away the constant term. Since

\[\Omega_ {d-1} = \frac{2\pi^{d/2}}{\Gamma\left( \frac{d}{2} \right)}, \quad \Gamma\left( \frac{1}{2} \right) = \sqrt{ \pi } ,\]we have

\[\text{loops} = \frac{1}{2^{d} \pi^{d/2}\Gamma\left( \frac{d}{2} \right)} \int_ {0}^{\Lambda} d k_ {E} \, k_ {E}^{d-1} \ln(k_ {E}^{2}+U''(\overline{\phi})-i\epsilon).\]For now let’s assume $U’’(\overline{\phi})$ is a positive constant, and neglect $-i\epsilon$, for whenever we need it we can always put it after $U’’$. Define two dimensionless new variables to replace $k_ {E}$ and $U’’$:

\[\boxed{ u := \frac{k_ {E}}{\Lambda},\quad t := \frac{U''(\overline{\phi})}{\Lambda^{2}}, }\]note that since $U’’(\overline{\phi})$ is supposed to be a constant, $t$ goes to zero at the $\Lambda\to \infty$ limit, making it possible for as to expand in powers of it. We have

\[\begin{align*} \text{loops} &= \frac{\Lambda^{d}}{2^{d} \pi^{d/2}\Gamma\left( \frac{d}{2} \right)} \int_ {0}^{1} d u \, u^{d-1} [2\ln \Lambda+\ln(u^{2}+t)] \\ &= \frac{\Lambda^{d}}{2^{d} \pi^{d/2}\Gamma\left( \frac{d}{2} \right)} \left[ \frac{2}{d} \ln \Lambda+\int_ {0}^{1} du \, u^{d-1} \ln(u^{2}+t) \right]. \end{align*}\]Regarding the integral in the line line, if we perform an integral by part first then use Mathematica code

Integrate[u^(d + 1)/(u^2 + t) , {u, 0, 1}, Assumptions -> {t > 0, t \[Element] Reals, d \[Element] Integers, d > 0}]

then we get an expression with Gaussian hypergeometric function\brace

\[\text{loops} = \frac{\Lambda^{d}}{d\,2^{d} \pi^{d/2}\Gamma\left( \frac{d}{2} \right)} \left\lbrace 2 \ln \Lambda + \left[ \ln(1+t)-2 \times \left( _ {2}F_ {1}\left( 1,\frac{2+d}{2}, \frac{4+d}{2},- \frac{1}{t} \right) \right) \right] \right\rbrace.\]So ugly. So I decided to just put the whole integral into Mathematica, I got instead

\[\boxed{ \text{loops} = \frac{\Lambda^{d}}{d\,2^{d} \pi^{d/2}\Gamma\left( \frac{d}{2} \right)}\left[ 2\ln \Lambda+\ln(1+t)- \frac{1}{t} \Phi\left( -\frac{1}{t},1,1+d/2\right) \right], }\]where $\Phi(-1,1,1+d / 2)$ is the Lerch transcendent function, defined as:

\[\Phi(z, s, a) = \sum_ {n=0}^{\infty} \frac{z^n}{(n+a)^s}\]where $z$ and $a$ are complex numbers, and $s$ is a complex parameter. The function is defined for $\left\lvert z \right\rvert < 1$ or $\left\lvert z \right\rvert = 1$ with $\Re(a) > 0$. Roughly speaking,

- $z$ is the value at which the series is evaluated.

- $s$ is a parameter that controls the power in the denominator.

- $a$ is a shift parameter in the denominator, which affects the starting point of the summation.

After we fix a dimension $d$, we would have fixed all two parameters of Lerch function, then we can expand $\Phi\left( -\frac{1}{t},1,1+\frac{d}{2} \right)$ at $-\infty$. It certainly feels weird but if you have experience with resurgence theory, it wouldn’t be your first time to expand something at infinity. One way to make you more comfortable with expanding at infinity is to consider the complex plane, compactify all the points at infinity to get a Riemann surface, then infinity becomes just another point on the sphere, and expanding about it is no less natural than expanding about any point.

Special case at $d=4$:

In this case we have

\[\begin{align*} u &:= \frac{k_ {E}}{\Lambda},\quad t := \frac{U''(\overline{\phi})}{\Lambda^{2}}, \\ \text{loops} &= \frac{\Lambda^{d}}{d\,2^{d} \pi^{d/2}\Gamma\left( \frac{d}{2} \right)}\left[ 2\ln \Lambda+\ln(1+t)- \frac{1}{t} \Phi\left( -\frac{1}{t},1,3\right) \right]. \end{align*}\]Let $x:= 1 / t$ and the last term concerning Lerch function becomes

\[- x\, \Phi\left( - x,1,3 \right),\quad x \to \infty.\]I like to drag the minus sign wherever the term goes, harder to make mistakes with a minus sign this way. Using Mathematica command to expand it at infinity

Series[LerchPhi[-x, 1, 3], {x, \[Infinity], 8}] // Normal

we get

\[- x\, \Phi\left( - x,1,3 \right)= - \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{x} - \frac{\ln(x)}{x^{2}} - \frac{1}{x^{3}}+\mathcal{O}(x^{-4}),\]insert this into the expression of loops we have

\[\text{loops} = \frac{\Lambda^{d}}{d\,2^{d} \pi^{d/2}\Gamma\left( \frac{d}{2} \right)}\left[ \ln(1+t) + t +t^{2} \ln t \right],\]where $d=4$ and $d 2^{d}\pi^{d/2} \Gamma(d / 2)=64\pi^{2}$. We have discarded surely irrelevant terms such as $\frac{1}{2}$, $2\ln \Lambda$ (they will be absorbed into the renormalization factor), and wrote $x$ in $t$. Next expand

\[\ln(1+t) = t - \frac{t^{2}}{2} + \frac{t^{3}}{3} + \mathcal{O}(t^{4})\]we get

\[\begin{align*} \text{loops} &= \frac{\Lambda^{4}}{64\pi^{2}}\left[ \ln(1+t) + t +t^{2} \ln t \right] \\ &= \frac{\Lambda^{4}}{64\pi^{2}}\left[ t-\frac{t^{2}}{2} + t +t^{2} \ln t \right] \\ &= \frac{\Lambda^{4}}{64\pi^{2}}\left[ 2t + t^{2}\left( \ln t-\frac{1}{2} \right)\right] \\ &=\frac{1}{64\pi^{2}}\left[ 2\Lambda^{2} U''(\overline{\phi}) + (U''(\overline{\phi}))^{2} \left( \ln \frac{U''}{\Lambda^{2}} -\frac{1}{2} \right)\right]. \end{align*}\]The last result agrees with Coleman’s 1-loop correction, which is shown in Eq. (44.51) in Lectures of Sidney Coleman on Quantum Field Theory, page 976.

For a 4D scalar theory, renormalizability strongly constraints the powers you could have on the interactions, it can be no more than $4$, otherwise some terms, such as $(U’’)^{2} \ln \Lambda^{2}$ will generate divergent terms proportional to $(\phi’’^{5})^{2}\sim \phi^{6}$, with no counter terms in the Lagrangian to absorb it, hence non-renormalizable. Coleman remarked in his lecture that

Non-renormalizable theories are sick no matter how you look at them; they’re no healthier from this vantage point.

However this is the old-fashioned point of view, Wilson will have something more to say on that. But that’s not for this note, here we proceed in the old-fashioned way, to continue to renormalized $\phi^{4}$ theory in 4D.

Including the counter terms, the effective potential reads

\[V(\overline{\phi}) = U(\overline{\phi})+U_ {ct}(\overline{\phi}) + \frac{1}{64\pi^{2}}(U''(\overline{\phi}))^{2}\ln[U''(\overline{\phi})]+(\Lambda\text{-dependent}),\]where $U_ {ct}$ include all the counter terms and we have written all the divergent terms as $\Lambda$-dependent. After using $U_ {ct}$ to counter the divergence, there could still be some finite part of $U_ {ct}$ left, depending on the renormalization condition. Also, to be mathematically strict, the parameter of $\ln$ function should be dimensionless, while $U’’$ is not. Anyway, this can be easily fixed by introducing another parameter $\mu$ with dimension of mass, and write $\ln(U’’ / \mu^{2})$, this $\mu$ will be fixed once the renormalization condition is fixed.

This formula (also with the generalization to $n$ different scalars) was first derived by Coleman and Weinberg: this Coleman and the other Weinberg, Erick Weinberg. Steve Weinberg refers to this work as “that paper with pseudo-Goldstone bosons and a pseudo-Weinberg.”

4. The Physical Meaning of the Effective Potential

Roughly speaking, the quantum effective potential $V(\overline{\phi})$ is the quantum generalization of classical potential $U(\phi)$, and $\overline{\phi}$ is the quantum generalization of the $\phi_ {c}$ (or $\left\langle \phi \right\rangle$ as Coleman used), the classical solution to the equation of motion. They agree at tree level and quantum correction kicks in at higher loops, as well the divergences, hence counter terms. Mathematically, $\left\langle \phi \right\rangle$ is the stationary point of the classical action, $\delta S / \delta \phi=0$ at $\left\langle \phi \right\rangle$; $\overline{\phi}$ is the same thing with quantum corrections, meaning it is the expectation value of $\phi$ with quantum corrections, it is the stationary point of the quantum effective action $\Gamma$, $\delta \Gamma / \delta \phi=0$ at $\overline{\phi}$. Physically, $V(\overline{\phi})$ gives the energy density of the vacuum in which expectation value of $\phi$ is $\overline{\phi}$.

When $V(\overline{\phi})$ has two local minima, things become interesting. Take the tilted double well for example, there are two local minima but the one with higher energy density is a false vacuum. If we start in the false vacuum, we expect to quantum tunnel (barrier penetration) into the true vacuum eventually. This tunneling phenomenon is non-perturbative.

What we are interested in is finding the vacuum state of a QFT model, then it is helpful to look into a similar situation in quantum mechanics. Let’s say we have some Hamiltonian $H$ with interaction, and we want to find the vacuum state $\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle$ that minimizes $\left\langle{\psi}\right\rvert H\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle$. We further want the the state to be corrected normalized, namely $\left\langle \psi \middle\vert \psi \right\rangle=1$. But that’s not enough, since in the case of QFT we require that the vev of $\phi$ is some certain value, denoted $\overline{\phi}$, here in the quantum mechanical example we also require the vev of some operator $A$ to be $\overline{A}$. To account for these two constraints, we use the Lagrangian multiplier method, defining the Lagrange function to be

\[L = \left\langle{\psi}\right\rvert H\left\lvert \psi\right\rangle-E\left\langle \psi \middle\vert \psi \right\rangle -J\left\langle{\psi}\right\rvert A\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle ,\]where $E$ and $J$ are Lagrange multipliers, and minimize it. We solve this variational problem with arbitrary $J$, and then eliminate $J$ from the problem to satisfy the constraint condition. We could define a function

\[\mathcal{W}(J) = \left\langle{\psi}\right\rvert -H+JA\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle ,\]now we assume $\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle$ is the ground state with all the constraints. Or, equivalently, $\left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle$ is the ground state of a modified Hamiltonian $H-JA$. This is similar to the field theoretic $S+\int J \phi$. Now we can replace $J$ by another variable using Legendre transform, define a new variable

\[\frac{d W(J)}{dJ} = \left\langle{\psi}\right\rvert A \left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle = \overline{A}\]and the Legendre transformed function

\[\Gamma := \mathcal{W}- J\overline{A},\]what would this $\Gamma$ be? Turns out, it is just the negative energy,

\[\Gamma = \left\langle{\psi}\right\rvert -H \left\lvert{\psi}\right\rangle = -E.\]Just like $\Gamma[\varphi]$ in QFT. The above quantum mechanical example is very similar to the field theoretical effective method of effective theory.

As remarked by Coleman, the method of effective action may be unreliable under certain circumstances, as he explained in his lecture,

…we may run into trouble if level crossing takes place. When the coupling constants are weak, another state that is not the ground state may come up and cross that energy level, and we may find ourselves following the wrong state as we sum up our Feynman graphs. If perturbation theory cannot tell us the true ground state energy, then we won’t get the true ground state energy for the constrained problem, either. On the other hand if perturbation theory serves to give the true ground state energy without constraint, it will also give us the true ground state energy with constraints.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: